-

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is weighing whether to place further restrictions on overdraft programs after a study released Thursday revealed consumers who opted in for such services are paying significantly more in fees.

July 31 -

The San Francisco bank abandons a practice that led to more overdraft fees and drew the ire of consumer advocates.

July 11 -

Some large banks have adopted more consumer-friendly policies, but many still engage in practices that seem designed to maximize overdraft fees, according to a new report from the Pew Charitable Trusts.

April 9

For the last four years, U.S. regulators have been requiring banks to offer their customers a choice on overdraft fees. And in response, most consumers have opted not to run the risk of incurring large fees in exchange for the ability to spend more than they have.

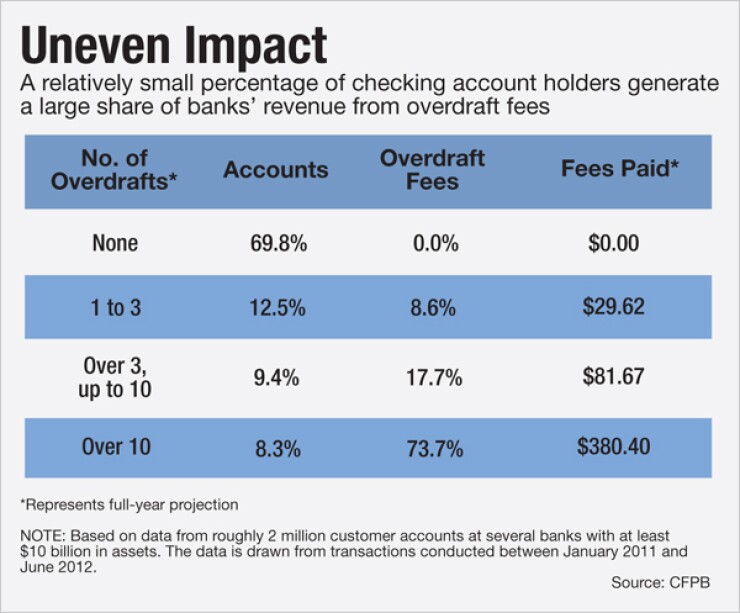

But for the minority of consumers who do opt in, overdraft fees can be enormously expensive. Around 8% of consumers paid overdraft fees at least 10 times per year, which cost them an average of $380 annually, the CFPB says.

Now a coalition of consumer advocates is calling for new restrictions on banks' ability to market overdraft coverage to their customers. After sending so-called mystery shoppers into branches in four states, the consumer groups say that branch employees often imply in their conversations with potential customers that they don't have a choice with regard to overdraft coverage.

"Even if the bank is following the rules in term of their written materials, what they're saying to consumers verbally is very confusing and sometimes downright inaccurate," said Dory Rand, the president of the Woodstock Institute, which is one of the groups that conducted the research.

The mystery shoppers went to 39 bank branches in Chicago, Durham, N.C., New York City and Oakland. Banks that got visits included Bank of America, BB&T, BMO Harris, Capital One, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, SunTrust, Union Bank and Wells Fargo.

The shoppers found that banks' explanations of their overdraft programs were inconsistent, and often unclear and incorrect, too. They also concluded that branch employees frequently did not clearly or correctly explain how overdraft fees are incurred. And they determined that bank employees frequently failed to explain the fact that consumers have to affirmatively choose overdraft coverage for ATM and debit card transactions.

Some of the shoppers reported that they were essentially given the choice of whether to pay hefty overdraft fees or a less costly service that links the consumer's savings account to their checking account, allowing for funds to be transferred when an overdraft occurs, without being told that choosing neither of those two services was also an option.

"The inconsistent and erroneous information bank personnel provided to mystery shoppers raises concerns about banks' training of staff and sales practices," states the report, which was co-authored by Woodstock, the New Economy Project, the California Reinvestment Coalition and Reinvestment Partners.

The research follows a

When asked for comment about the mystery shoppers' findings, Tom Crosson, a spokesman for the Consumer Bankers Association, noted that overdraft coverage is optional, and that consumers can revoke their enrollment at any time. He also pointed out that consumers receive written explanations of banks' overdraft policies.

"Banks are required to hand out fees disclosures to all consumers upon account opening," Crosson said in an email. "These disclosures are also available online and at branches."

The CFPB

The consumer groups that conducted the mystery shopping are pushing the CFPB to enact a series of tight restrictions on overdraft coverage, including a ban on the reordering of transactions from high amount to low amount, a practice that maximizes banks' fee revenue, as well as a prohibition on all overdraft fees incurred as a result of an ATM withdrawal or a debit card purchase.

The consumer groups' report also recommends several additional restrictions that could offer the CFPB a fallback position if the agency decides not to adopt the advocates' more sweeping proposals.

The secondary list of recommendations includes a ban on banks providing financial incentives to branch employees for the sale of overdraft products, the creation of a uniform standard for how banks should verbally describe overdraft fees, and required training on that verbal standard for branch employees.

If any of those recommendations are eventually adopted by the CFPB, they would further restrict a revenue stream that has been somewhat curtailed but remains lucrative for banks.