There is little question that China’s tariffs on U.S. soybeans will slow exports and crimp the profits of many farms, but how they affect the banks that lend to soybean farmers will depend largely on how long the trade war persists and how well bankers prepare customers for the inevitable slowdown.

If bankers begin taking steps now to refinance existing agricultural loans or help farmers sell their products in markets outside of China, then the damage to banks’ balance sheets should be minimal — at least in the short term, bankers and industry experts say.

But if their efforts fall short and farmers are unable to recoup what could be billions of dollars in lost export revenue, then banks could be looking at a costly rise in farm loan delinquencies.

“It’s definitely at the forefront our minds and our customers’ minds,” said Brian Johnson, CEO of the $1.3 billion-asset Choice Financial in Fargo, N.D., where 23% of its loans are to farmers, much of it for soybeans. North Dakota exported $1.1 billion of soybeans worldwide last year, according to federal data.

China imposed the 25% tariff on soybeans and other U.S. products in response to President Trump’s decision to assess a 25% tariff on $34 billion worth of Chinese goods entering the U.S., which took effect last week. The trade war escalated this week when the Trump administration said it would impose tariffs on an additional $200 billion worth of products imported from China.

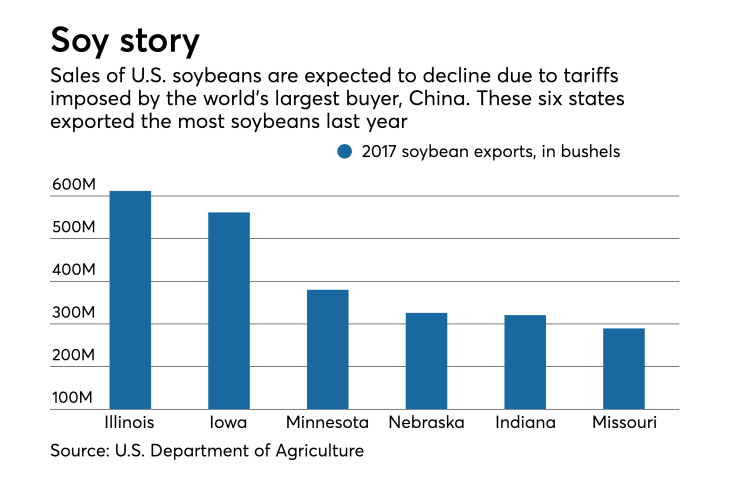

China is the world’s largest buyer of U.S. soybeans, so if it wanted to impose a tariff that could most hurt the American farm economy, it chose the right product, according to

China’s retaliation against Trump has had an immediate impact on farm exports. Total lost soybean sales for 2018 exceeded 5 million metric tons through June 28, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture data

“We are disappointed that agriculture continues to be placed in the middle of the tariff debate with China,” Lynn Rohrscheib, chairwoman of the Illinois Soybean Association,

The steep rise in cancellations comes at a time when farmers and the banks that lend to them are already grappling with a decline in commodity prices, said John Blanchfield, principal at Agricultural Banking Advisory Services. Farmers had already been struggling to meet loan payments and that problem may now worsen, said Keith Ahrendt, chief credit officer at the $11.9 billion-asset Bremer Bank in St. Paul, Minn.

“Credit quality has been a challenge for farmers the past few years anyway and we’ve been working with a lot of our customers that are struggling,” Ahrendt said.

Reduced revenue from soybean exports will also extend to farmers’ other financial decisions, Blanchfield said. They will likely delay making large capital expenditures, which will also hurt banks, particular in such states as Illinois, Iowa and Minnesota that are major soybean exporters.

“The effect of lower soybean prices will back up into the system in other ways,” Blanchfield said.

Bremer intends to offer several alternatives to farmers who lose business due to China’s soybean tariff, Ahrendt said. A primary option will be to refinance loans using farmers’ equity in real estate holdings.

“We’ll refinance their overall debt to get them better cash flow,” Ahrendt said. “The whole challenge right now is that prices are already down and credit quality is going to be stressed [by the tariff].”

About 19% of Bremer’s $1.2 billion portfolio of farm and farmland loans is directly tied to soybean farming, Ahrendt said.

Bremer also plans to make greater use of loan guarantees from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which allow banks to extend amortization periods for distressed borrowers.

Choice Financial also plans to explore alternatives with ag borrowers, such as allowing some to make interest-only payments, Johnson said.

“We have to possibly look at no principal payments being made,” Johnson said. “You’ve got to find temporary or interim solutions.”

Another potential option is helping farmers find ways to sell their products to countries other than China, Ahrendt said.

“One of the positives in my mind if that the world only has so many soybeans and the U.S. and Brazil are the only major producers,” Ahrendt said. “Pick another country to start selling to. There’s got to be another place for soybeans to go.”

Bankers and analysts say that it’s too soon for credit quality issues tied to the soybean tariff to materialize in financial results. Banks will begin reporting second-quarter earnings later this week, but it’s very unlikely that the tariff has had an effect yet, Johnson said.

“It will probably start showing up in the first quarter of 2019,” Johnson said. “I don’t expect to see it yet in banks’ [loan-loss] provisions.”

Still, investors will ask bankers during second-quarter earnings calls to give estimates on potential problems tied to the tariff, said Chris Marinac, an analyst at FIG Partners. Even banks that don’t do much farm lending still have some indirect exposure to agriculture and could provide insight, he said.

“They have businesses that support the farmers,” Marinac said. Investors will ask bankers “how good are people today? Where do you see them in six months?” he said.