Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

Time and again, the nation's largest banks have said that they do not do business with firms in the marijuana industry because pot, while legal in 29 states, remains illegal under federal law.

"At Bank of America, as a federal regulated financial institution, we abide by federal law and do not bank marijuana-related businesses," the Charlotte, N.C.-based bank

These blanket denials have helped the megabanks keep a low profile on a sensitive issue: the cannabis industry's touch-and-go relationship with the U.S. banking system. But the reality inside of big banks is murkier than their public statements suggest.

Newly examined records show that numerous marijuana-related entities have had accounts at the four biggest U.S. banks in recent years. The records, which are

The analysis found that out of 84 applicants to operate medical marijuana dispensaries in Massachusetts, 29 reported having access to funds in at least one account at Bank of America, Citi, Wells or JPMorgan, or at one of their subsidiaries. Of the 29 applicants that had access to funds at one of the four big banks, 17 had a connection to B of A. The analysis covered applications filed between June 2015 and September 2016.

For 19 of the 29 applicants, these bank accounts were in the names of individuals who were involved in efforts to open pot dispensaries, whose connection to the cannabis industry may not have been obvious to bankers. But in other instances, the accounts were in the names of well-known cannabis firms that were operating in other states.

The findings raise questions about the extent to which the big banks are screening customers to determine whether they are part of the cannabis industry. The Obama administration has not made the enforcement of federal marijuana law a top priority, which has reduced pressure on banks. But that could change under the incoming Trump administration, whose attorney general nominee has expressed hostility to pot.

The Massachusetts records also complicate two frequently told narratives about the U.S. pot industry. One is that marijuana businesses cannot get bank accounts, and

"A commonly held belief seems to be that small institutions are more likely than large institutions to have marijuana-related accounts, knowingly or otherwise," said Steven Kemmerling, the CEO of MRB Monitor. "The data seems to challenge those assumptions and raises the question of whether any financial institution is adequately prepared to identify and manage this particular risk."

In 2015, a firm called Mass Organic Therapy applied to the state of Massachusetts to sell medical marijuana. One of the documents that the company submitted to the state asked prospective business owners to show that they had at least $500,000 available and in their control.

Mass Organic Therapy listed funds in the name of a company called PalliaTech Inc., which had committed 62% of the initial capital for the venture.

The filing includes a

"Please let me know if you need any additional information and thank you as always for being a fantastic client," the Citi banker's letter stated. "We appreciate it!"

At the time, Long Island-based PalliaTech

By late 2015, PalliaTech

PalliaTech did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

Citi terminated the PalliaTech account after a review in early 2016, according to a source familiar with the matter.

The New York-based bank said in a statement: "Citi abides by federal law and does not provide financial services to customers that engage in activities prohibited by federal law."

A second applicant was a firm called Mission Massachusetts Inc., which recently received preliminary approval to open a medical pot dispensary in Worcester. The company's CEO and two of its directors were shareholders in 4Front Ventures, a cannabis firm in Phoenix.

On a document submitted to the state, Mission Massachusetts listed funds in the name of 4Front Ventures. As of May 2015, 4Front Ventures had $1.8 million in a Bank of America business checking account, according to the

By 2015, 4Front had been operating in the medical marijuana industry in Arizona, Illinois, Nevada and California, according to a document filed in Massachusetts. And the company does not appear to have tried to hide its involvement in the industry from the general public. "Defeat prohibition through sensible regulation," 4Front's website read in 2015.

A spokesman for 4Front Ventures did not respond to requests for comment.

A Bank of America spokesman declined to comment on specific customers, but did say: "We're a nationally chartered financial institution that complies with federal law."

It is not clear whether bankers at either Citi or Bank of America knew that the accounts discussed in this article were connected to the marijuana industry. Given the scrutiny that cannabis firms generally face from financial institutions, they may have an incentive to obscure their business plans.

"If they tell the truth, they will either have to pay high fees and endure enhanced due diligence or they'll likely lose an account," Kemmerling said. "But if they are opaque, they may be able to fly under the radar for a period of time, if not indefinitely."

At the same time, banks have long-standing obligations to conduct customer due diligence. For customers that are classified as higher risk, banks are expected to take additional steps, such as asking about the purpose of the account both when it is opened and throughout the relationship.

Spokesmen for Citi and Bank of America declined to comment on steps those banks take to ensure that marijuana businesses cannot open or maintain accounts.

JPMorgan Chase uses a combination of risk-based methods to comply with regulations related to knowing its customers and combating money laundering, according to a spokeswoman, who declined to provide more specific information. Wells Fargo's policy is not to discuss internal practices and procedures that are confidential and proprietary, a spokeswoman said.

The Federal Reserve Board and Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. declined to comment on the record for this article.

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, which in 2014 issued guidance designed to encourage more banks to serve the pot industry, also declined to comment. Federal data last year

Bryan Hubbard, a spokesman for the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, said that the agency expects the banks it regulates to follow applicable guidance, including the 2014 document from Fincen, which mentions red flags that banks can consider.

One pot industry source said that he knows of certain marijuana businesses that are banking with large financial institutions, in some cases because they have a relationship with a branch manager who is allowing the account to remain open.

"A lot of these larger national banks are actually doing it," said Lance Ott, a principal at Guardian Data Systems, a firm that helps marijuana dispensaries with their financial management.

Most of the financial institutions that have publicly acknowledged their willingness to serve the cannabis industry are small banks and credit unions.

Sundie Seefried is the CEO of one of those institutions, Partners Colorado Credit Union. She is also the author of a 2016 book titled Navigating Safe Harbor: Cannabis Banking in a Time of Uncertainty.

Seefried said that her credit union has developed an extensive process for vetting potential clients in the pot business, which includes a three-phase interview process prior to due diligence work.

She speculated that big banks may be taking on certain marijuana clients in an effort to better understand the industry. "It's probably a smart move on their part to learn the business, and learn from somebody who's a trusted customer."

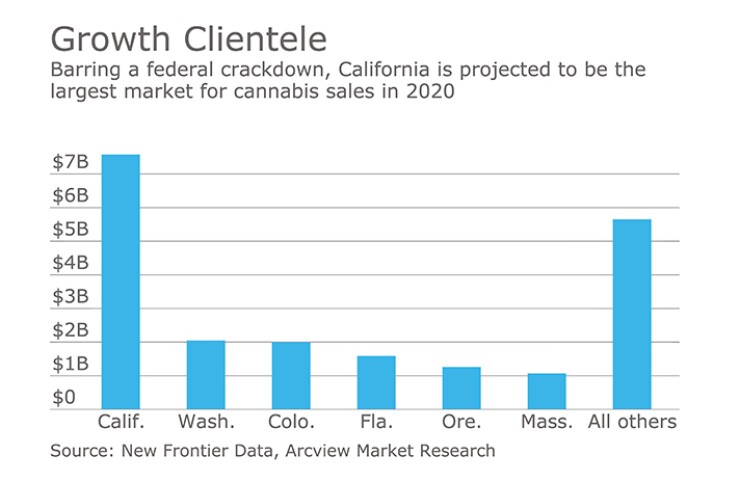

Massachusetts represents only a small fraction of the U.S. pot industry, but there is reason to believe that marijuana businesses elsewhere generally have access to the banking system.

Rick Riccobono, the former director of banks at the Department of Financial Institutions in Washington state,

"People say it's a total cash business in Colorado and Washington," Riccobono told a reporter. "Quite the opposite. We've actually gotten this thing pretty far along." (Riccobono left the agency late last year).

Still, the pot industry's access to the banking system often comes at a steep financial cost — industry sources

Today there are fears that the incoming Trump administration will move in the opposite direction and crack down on violations of federal law.

At a Senate hearing Tuesday, Sen. Jeff Sessions, the president-elect's nominee for attorney general, noted that Congress has made the possession and distribution of marijuana illegal in every state.

"If that's something that's not desired any longer, Congress should pass a law," Sessions, R-Ala., said. "It's not so much the attorney general's job to decide what laws to enforce."