WASHINGTON— Although banks are only starting to grapple with the rising popularity of cryptocurrencies, a framework from global banking regulators outlining possible capital charges for them is a likely preview of how financial institutions could soon come to view digital money.

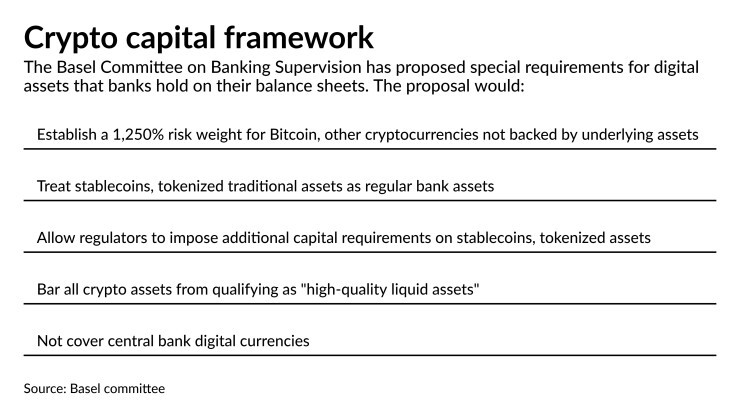

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision

While the proposal is likely years away from adoption and could morph over time as the digital asset space continues to evolve, as even the committee acknowledged, many industry experts were encouraged by the framework.

“It's a strong indicator that the regulators are fully conscious and sensitized to the developments that are going on in this space,” said Stephen Gannon, an attorney at Murphy & McGonigle.

The panel of global regulators also suggested that other digital assets like stablecoins, which are tied to real-world assets and currencies, be subject to less stringent capital rules that would more closely resemble capital regulations for traditional bank assets.

In particular, that differentiation between digital asset classes by banking regulators was “revolutionary,” said Georgia Quinn, general counsel at Anchorage Digital Bank, a financial institution that provides cryptocurrency-related services.

“Stablecoins are a different type of asset and they don't have the same volatility concerns,” she said. “I'm really excited that they're finally getting some credit somewhere.”

While the Basel committee’s proposal asked for public comment on whether there should be potential capital add-ons to what it called “group one” cryptoassets (tokenized traditional assets and assets with stabilization mechanisms, like stablecoins), regulators appeared to acknowledge that those assets posed less of a risk to banks than assets like Bitcoin.

That could pave the way for banks to warm to holding stablecoins or other tokenized assets.

“The first step is to recognize that not all digital assets will necessarily fit into one basket, and the Basel committee certainly recognizes that,” said Bruce Mizrach, a professor in the economics department at Rutgers University. “There's the possibility that some of the truly stable among the stablecoins will, in fact, be treated similar to cash-like assets.”

Gannon agreed that it was important for regulators to recognize that the “thousands of cryptocurrencies out there” are structured differently and thus pose distinctive risks to bank balance sheets.

“My guess is that down the road, in terms of capital treatment, there'll be some discrimination based on the different kinds of digital assets that are there, just like there is differentiation between capital treatment in connection with different types of debt instruments and different types of different classifications of equity,” he said.

At a point in time where much of the public conflates stablecoins with cryptocurrencies writ large, the Basel committee proposal could serve to highlight the crucial differences between the asset classes, added Mizrach.

“Basel is hopefully helping people wake up to the fact that the digital asset space is not just Bitcoin, or not just Bitcoin and Ethereum,” he said. “There's a range of things.”

While banks are not currently clamoring to hold cryptocurrencies on their balance sheets, there could be potential benefits to holding stablecoins in the future, Quinn said.

“It diversifies the asset class it allows them to gain exposure to, and potentially protects from inflation,” she said. “U.S. federal banks don't necessarily have this problem because they're generally backed by U.S. dollars, but for central banks in other jurisdictions where that currency may not be as stable, this might be a nice addition to their portfolio.”

However, the capital charge the proposal suggests imposing on assets that are not tied to a fixed value, like Bitcoin, would likely have the effect of discouraging banks from holding those assets on their balance sheets, said Mizrach.

“It seems to be very unlikely under these rules as proposed, given the group two assets, that there will be prop desks at JPMorgan trading Bitcoin and Ethereum in large quantities,” he said. “The capital cost is just too high.”

Quinn noted that banks have generally not been interested in holding assets like those anyway, given how volatile they have proven to be.

“I don't think there are any banks out there that are wanting to hold crypto on their balance sheets,” she said. “No bank is saying, ‘Oh, I want to hold crypto on my own balance sheet. I'm going to hold crypto as my capital reserves to back the deposits of clients.’ ”

Instead, many banks are looking to offer custodial services for their customers’ digital assets, which wouldn’t come with a hefty capital charge.

“JPMorgan, Bank of New York Mellon and so on want the custodial asset business, because custodial questions have been extremely important,” said Mizrach.

So why suggest a capital charge on those types of digital assets in the first place if banks aren’t interested in holding them? It may have to do more with sending a message to the public, said Quinn.

“I think people maybe want to get ahead of something just to make it clear that nobody in their right mind is going to do this, but just also so the public understands that, ‘Don't worry guys, the banking system is sound, please continue to deposit your assets in these banks,’ ” she said.

Gannon agreed that underscoring the proposal is a continued focus by global regulators on the safety and soundness of the banking system.

“I think [the regulators] believe that innovation is obviously necessary, and they're not trying to stand in the way, but at the same time, they have got to be concerned about the safety and soundness of the banking system,” he said. “They want to make sure that they're taking actions that in their minds, at least, are consistent with ensuring that banks aren't overly exposed to assets that are risky.”