WASHINGTON — After a pledge by Goldman Sachs at the end of 2019 to stop financing projects that directly support coal mining and Arctic oil exploration, pressure from Capitol Hill and environmental lobbyists is mounting on other banks to take similar stands.

Democratic lawmakers and environmental groups are hopeful other banks will follow Goldman's lead, saying that economic risks about the future of the fossil fuel industry are coming into view.

“There's cold, hard economic arguments to be made for reducing and stopping investments in fossil fuels,” said Ben Cushing, a campaign representative with the Sierra Club’s Beyond Dirty Fuels campaign. “Even if you're only looking to make a buck, I think big banks and financial institutions around the world are recognizing that this is not even a good way to make money, let alone what their responsibility is for protecting the planet.”

The pressure campaign comes as activist investors also speak up about the financial services sector's role in climate change. JPMorgan Chase recently

Like other polarizing issues such as the financing of firearms entities, banks are in a difficult spot. Just as voices on the left urge banks to pull back from lending to fossil fuel interests, voices on the right have in the past said such decisions reflect political bias.

Many institutions would also take a clear hit to their lending portfolio if they took a stand similar to Goldman's.

Some observers say the decision to provide funding to the energy sector is not a political one, but instead rooted in business and the desire to maximize a return on investment.

“If you're a large bank and you've got an energy company as a customer, I just don't think right now the leverage that these activists have is sufficient to, really have these banks change what's primarily a financial and economic decision on their parts,” said Rolland Johannsen, a senior consulting associate at the Capital Performance Group.

"For the banks certainly that have a large presence in the energy sector, they're going to continue to do business with and finance fossil fuel companies," Johannsen said. "As long as we're still dependent on fossil fuels, they are going to be a part of that equation.”

Joe Pigg, senior vice president of fair and responsible banking and mortgage finance at the American Bankers Association, said banks of all sizes are focused on climate change policies, but financial institutions have to weigh numerous competing interests before determining a policy on fossil fuels and other pressing topics.

"Certainly in any institution, their stakeholders are going to include environmentalists, [but] they're also probably going to include others that might hold a different view," Pigg said. He added that economic considerations are also "part of the process" in determining whether to curtail or expand financing for a particular industry.

"As a general matter, banks approach this the same way that they approach all of their other choices. They base it upon what their stakeholders' expectations are ... and that changes obviously over time and in this space that is certainly changing pretty quickly," Pigg said. "But that doesn't necessarily mean there is any uniform response. That's going to vary from institution to institution based upon what their stakeholders' views are.”

In December, Goldman said it would hold back financing that directly supports new coal fired power generation that does not include "carbon capture and storage or equivalent carbon emissions reduction technology." The bank added that it "will decline any financing transaction that directly supports new upstream Arctic oil exploration or development."

Just last week, the Royal Bank of Scotland announced that it would cut its greenhouse gas emissions to zero by the end of this year and limit its financing activity that impacts climate change by at least half by 2030, including a significant curtailing of loans to coal-related companies. Other international banks taking similar steps include Crédit Agricole and Société Générale.

“You've seen a real surge in momentum ... with more and more banks around the world adopting policies to rule out new fossil fuel financing,” said Cushing.

After Goldman's announcement, 16 Democratic senators sent a letter to 11 of the largest banks calling them to take similar steps to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

"The scale of your banks' assets individually, let alone together, give you the ability to drive change in protecting the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and in shifting towards a U.S. financial sector that effectively analyzes and plans for climate risks," the senators wrote in the Jan. 30 letter.

Environmental groups say they are gearing up to put more pressure on the industry.

“There just really has been a really remarkable convergence of attention from bank investors and clients and potential customers and regulators and grassroots activists all looking at banks' contribution to climate change and all pointing in the same direction, spotlighting the problem and calling them to draw it down,” said Jason Disterhoft, a senior finance campaigner at Rainforest Action Network.

The Sierra Club plans to attend the annual general meetings of shareholders at the six largest U.S. banks this spring to urge them to address climate change, Cushing said.

Yet a withdrawal from fossil fuel financing would not be an easy proposition. Although some banks have adopted restrictive fossil fuel financing policies since the Paris Agreement was signed, such financing is generally on the rise, despite research showing that failure to cut carbon dioxide emissions by 45% by 2030 in order to prevent the globe from warming above 1.5 degrees Celsius could have catastrophic results.

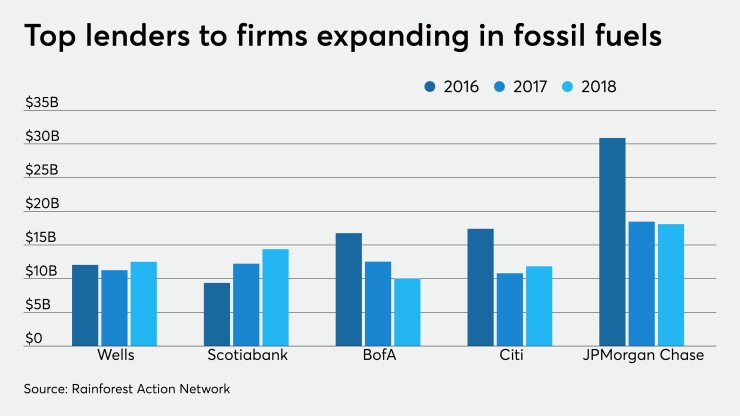

U.S. banks have poured $1.9 trillion into fossil fuel-related projects since the agreement was enacted in 2016. JPMorgan Chase has invested the most in Arctic oil and gas, while JPMorgan Chase, Citi and Bank of America have the biggest stakes among U.S. banks in ultra-deepwater oil and gas, according to the Rainforest Action Network’s 2019 Banking on Climate report.

“There are banks that have a large presence in the energy sector and they're going to diversify their risk across different types of energy companies and I don't think at this point, reputational risk or political risk is entering into the equation of most large banks that choose to do business with those companies,” Johannsen said.

Meanwhile, any decision by a bank to curtail lending to the fossil fuel industry risks blowback from GOP lawmakers who have been critical of decisions by banks to voluntarily cut off financing to particular controversial industries, like gun manufacturers, payday lenders and private prisons.

Many have argued that if a business is legal, a bank should be expected to serve it. Senate Banking Committee Chairman Mike Crapo, R-Idaho, urged big-bank CEOs last year

Their point was backed up by testimony last month from Comptroller of the Currency Joseph Otting. Under questioning by House Financial Services Committee member Bill Posey, R-Fla., Otting noted that CRA "says that the bank should serve the entire community to which they provide banking services." He added, however, "I don't necessarily feel if I elect not to bank a particular company that it's in violation of the Community Reinvestment Act."

Goldman Sachs' decision triggered immediate criticism in Alaska, where the office of the state's GOP governor, Mike Dunleavy, sent a letter to Goldman CEO David Solomon saying the state would consider cutting business ties with the financial giant.

The bank's fossil fuel "policy is in direct conflict with the goals of the State of Alaska and threatens Alaska's oil and gas industry, one of the State's primary revenue sources and economic drivers," wrote Michael Barnhill, acting commissioner of Alaska's Department of Revenue.

But groups urging banks to restrict lending to the fossil fuel industry say their case is bolstered by evidence of that industry's economic decline.

The energy sector was the worst performing sector in the S&P 500 in 2019, and declined 11% in the last month of the year alone. The demand for coal, in particular, has dropped rapidly, and analysts expect that trend to continue.

Both the economic and reputational risks that come with investments in the sector are starting to outweigh the potential revenue and client relationship benefits, said Dan Saccardi, senior director of the company network at Ceres, a nonprofit organization focused on sustainability issues.

“As we're coming to a point where [banks are] looking at the declining size of some of those loan books, I think there's starting to be some evaluation of what is that marginal benefit versus some of these other risks,” he said. “So I think that's why we're starting to see some of the movement like we saw from Goldman at the end of last year."

He added that if a bank was weighing "purely a 'social consideration,' then perhaps it wouldn't be the bank's place to make those decisions." But looking toward the future, the issue becomes one of “fundamental risk,” he said.

Disterhoft agreed that business considerations combined with investors’ growing focus on "environmental, social and governance" factors will strengthen the case for banks to reduce their exposure to fossil fuels.

“Increasingly, the same business considerations that are applied to coal are increasingly applying to fossils more broadly,” he said. “Whether that's tar sands or Arctic oil or fossils in general, I think the business case is increasingly pointing in the same direction as the social responsibility case.”