Under construction on a parcel of land in Boston’s inner city that has been vacant for more than four decades is a $21 million, five-story apartment complex that will eventually house 40 low-income families or individuals.

Boston Private Bank is providing much of the financing, though Esther Schlorholtz, its director of community investment, said it could not do so without a fair amount of government support.

To cover the costs of building and operating the property and still keep rents affordable for tenants, the developer needed to obtain several layers of financing assistance that included two different types of tax credits and zero-interest loans or grants through two federal programs administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Those federal programs, Schlorholtz said in an email, “are key to making the entire financing work. They fill the project gap that no one else funds.”

But will those programs, which bankers and housing advocates say are crucial to helping solve the country’s chronic shortage of affordable housing, be around much longer?

The Trump administration's budget for fiscal 2018 calls for slashing HUD's budget by 13% from current levels, largely by eliminating the Community Development Block Grant program and the HOME Investment Partnerships Program.

The two programs have combined to support the construction and rehabilitation of millions of affordable housing units since their inception, and if they are eliminated, many projects might never get off the ground, bankers say. Their combined budget is roughly $4 billion annually, and on the Boston project alone Community Development Block Grant and HOME funds accounted for $3.3 million, or 16%, of the total financing.

Schlorholtz said that without those programs, “there will be fewer projects to finance and also fewer development proposals that offer quality homes that are financially feasible over the long term.”

Alexander Beaumariage, the affordable housing program manager at Cleveland-based KeyCorp, agreed.

“If we were to eliminate those programs, it’s just that many more properties that wouldn’t get built,” he said.

HUD officials also have pointed out that there are other government programs available to help close gaps in financing affordable housing projects, including one offered through the Federal Housing Administration, an agency within HUD. A number of states have housing trust funds that can help plug financing holes, too.

Still, the demand for affordable housing already far exceeds the supply, and bankers and housing advocates fear that the gap will only widen if the two HUD programs are eliminated. Making matters worse, the cuts could come at a time when some banks are already shying away from affordable housing deals because the prospect of

“We are already in a state where sources of funds for construction and rehab of affordable housing have shrunk,” KeyCorp’s Beaumariage said. “We need those programs now more than ever.”

There is little debate that the need for more affordable housing is dire, particularly in high-cost metropolitan markets like New York, Boston, Washington and San Francisco. And while the shortage affects adults and families at all income levels, those at the lowest end of the spectrum are struggling the most.

For every 100 households with incomes at or below 30% of the area median income, there are only 29 “adequate and affordable” rental units available, down from 33 in 2007 and 37 in 2000, according to the Urban Institute. The National Low Income Housing Coalition estimates that more than 7 million units would need to be developed nationwide to satisfy demand.

The HOME and Community Development Block Grant programs are similar in that funds from both are distributed to states and can be used for a wide range of housing-related activities, including rental assistance for low-income household, helping existing homeowners refurbish homes or helping to fund larger community-development initiatives.

The block grant program was established in 1974 and has an annual budget of around $3 billion, while HOME was established in 1990 and has an annual budget of just under $1 billion.

Thomas FitzGibbon, a former executive with MB Financial in Chicago and now an independent consultant, said that to make projects affordable for both the developer and residents, banks need programs like HOME and block grants to close deals. He added that if the programs are eliminated or curtailed, some banks could have trouble meeting their Community Reinvestment Act obligations.

“Under CRA, one of the things banks are challenged to do is drive capital into capital-starved markets, and it can be hard to do that without some kind of government subsidy,” he said.

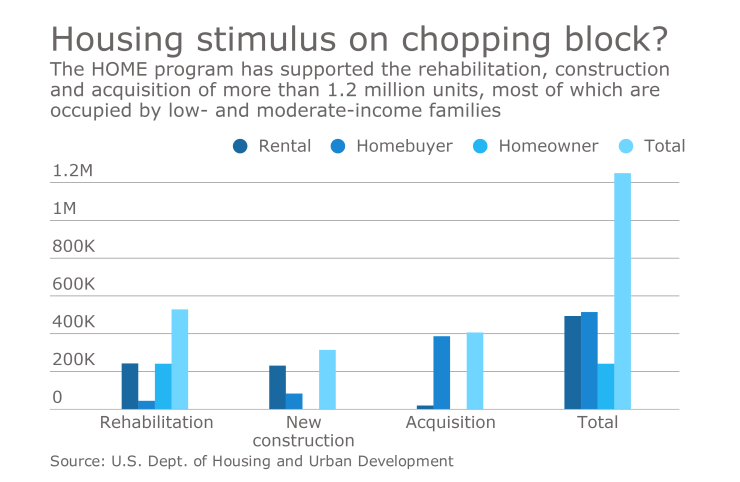

Benson “Buzz” Roberts, the president and CEO of the National Association of Affordable Housing Lenders, said that the programs have provided a strong return on their investments. Citing HUD’s own numbers, he said that every dollar of HOME funds invested in the development of low- and moderate-income housing since 1992 has brought in $4.26 of private investment. In all, it has helped developers build, fix up or acquire more than 1.2 million homes and apartments.

“That’s a lot of production,” he said. HOME “has had a tremendously positive effect on distressed communities, and it’s been very cost-effective.”

That’s a message Roberts and other housing advocates hope to get across to members of Congress as they debate the HUD budget in the coming months.

“Affordable housing is not only a roof over somebody’s head. It allows kids to do better in school, for families to stay healthier, for workers to have shorter commutes,” said Garth Rieman, the director of housing advocacy and strategic initiatives at the National Council for State Housing Agencies. “There’s a hopefulness that once Congress understands that, they will continue to support these programs at least at the current levels of funding.”