-

While mainstream lenders are poised to get ample attention from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the new agency made clear Thursday it will not stop there.

June 23 -

House Republicans released an appropriations bill Wednesday that would slash funding for financial services agencies by 9% in 2012. The measure would also cap mandatory funds for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau at $200 million — the current limit is $600 million.

June 15 -

While most of the attention so far has focused on who will be the director of the CFPB, would-be employees are anxious about how the agency plans to fill the lower ranks.

June 10 -

President Barack Obama is considering nominating Raj Date, a former banker with Capital One Financial Corp. and Deutsche Bank AG, as head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, according to a person briefed on the process.

June 9 -

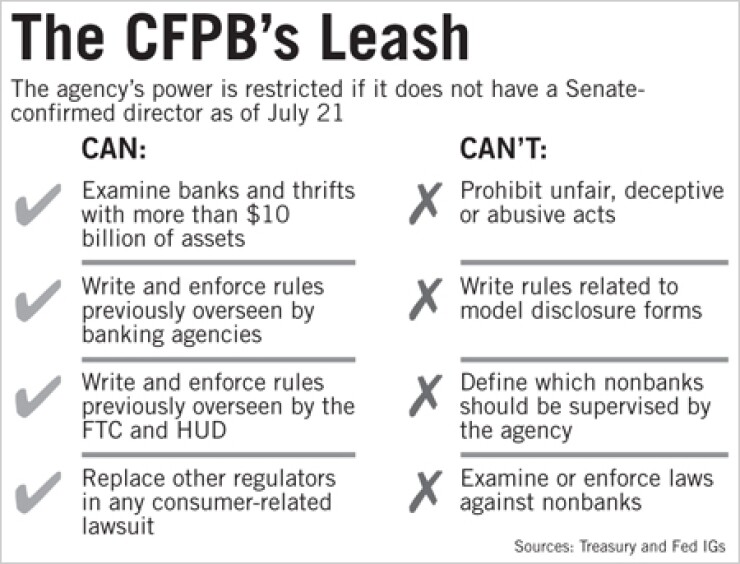

Depending on which political party you talk to, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is either the most powerful federal agency ever created, or the most constrained.

June 2 - WIB PH

Analysts said personally attacking the de facto head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is a smart political strategy for the GOP — but also, strangely, helps the Democrats.

May 27

WASHINGTON — While some bankers are secretly gleeful the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau does not yet have a director, they are the ones likely to pay a heavy price as a result.

Although the agency will be constrained on July 21 if it does not yet have a Senate-approved leader, those restrictions largely apply to nonbanks, not the banking system. As a result, the CFPB will be free to examine and take action against banks with more than $10 billion of assets, while their nonbank competitors face no extra scrutiny.

Such a situation flies in the face of both Congressional intent and the industry's adamant wish that they face an even playing field with other lenders when it comes to consumer protections.

"The objective in creating the consumer bureau was to have an agency that would focus more on consumer protection than the banking agencies had, and would be able to fully scrutinize larger non-banks in particular," said Amy Friend, a managing director of Promontory Group, and a former chief counsel for the Senate Banking Committee. "It will be hamstrung if it lacks a permanent director, to the detriment of banks."

Indeed, the CFPB's enforcement division will have no one else to focus on but banks come July 21, industry watchers say.

"It's common sense that if you can't regulate one, you regulate somebody else," said Richard Hunt, the president of the Consumer Bankers Association. "They're going to regulate the people they know, and that's banks. And that's fine, we don't mind being regulated, but the intent of the administration was to have a level playing field, and this does anything but create a level playing field."

Both political parties share the blame.

The White House has appointed Elizabeth Warren as a special advisor to the Treasury secretary to help lay the foundation for the new bureau, which assumes some of its authorities on July 21. But it has yet to nominate a permanent director for the bureau, leaving a gaping hole in one of the central tenets of its financial reform package.

On the other hand, Republicans have vowed to block the confirmation of any CFPB director, regardless of political party, until significant changes are made to the bureau's structure - changes that Congress rejected once already. But efforts to hobble the bureau by blocking the confirmation of a director may have the opposite of their intended effect. By preventing a permanent leader from stepping in, they may be turning up the heat on banks.

Friend said Congress never intended to give a directorless bureau some powers and not others. Rather, the statute was written in such a way that distinguished existing authorities from brand new ones.

"It was the farthest thing from Congress' mind that, a year from the date of enactment, there would not be a permanent director," Friend said. "If the problem had been anticipated, it would have been drafted to get around it."

As written, however, Dodd-Frank allows the bureau to carry out certain functions under the Treasury secretary's interim authority after the July 21 transfer date, even if there is no director, according to a report from the inspectors general of the Treasury Department and Federal Reserve.

Although not everyone is convinced the powers would be so broad — representatives from some industry groups have said they believe the bureau can't do much of anything without a director — most lawyers and industry observers have relied on the IG report for guidance on the bureau's authority.

According to the report, the bureau has the authority to prescribe rules, issue orders and produce guidance related to consumer financial laws that were previously enforced by other bank regulators. It can also conduct exams; prescribe rules, issue guidelines, and conduct studies under the consumer laws previously enforced by the Federal Trade Commission.

It may also conduct all consumer functions relating to fair lending laws previously enforced by the Department of Housing and Urban Development; enforce all orders, resolutions, determinations, agreements, and rulings that have been issued or allowed to become effective by the transferring agencies; and replace the other regulators in any lawsuit or proceeding that began prior to the transfer date.

While that grants the CFPB substantial leeway over banks, the IGs said the CFPB could not take on anything new under the law.

"The secretary is not permitted to perform certain newly-established bureau authorities if there is no confirmed director by the designated transfer date," the report said.

For example, it may not conduct examinations of nonbanks, or prescribe rules defining which non-banks are subject to supervision, or establishing recordkeeping requirements for non-banks. It also may not prohibit unfair, deceptive or abusive practices; prescribe rules and require model disclosure forms to ensure that the features of financial products or services are fairly and effectively disclosed; or prescribe rules requiring non-banks to file limited reports with the bureau.

While their oversight authority is limited, CFPB officials aren't entirely ignoring non-banks, however.

The agency put out a proposal last month - the first step in establishing its non-bank supervision program - that identified several credit-related sectors in which it plans to oversee large non-banks. On a conference call with reporters, Warren reiterated the agency's commitment to "leveling the playing field for all financial services providers."

"Consumers deserve the peace of mind that financial companies — banks and nonbanks — are following the rules," she said.

But it's always been easier to regulate banks because the infrastructure already exists, said Jo Ann Barefoot, a co-chair of Treliant Risk Advisors and a former OCC official. Examiners are already on site, and it's easy to ask them to look at more issues while they're there, whereas no precedent exists for supervising non-banks.

"That problem will be compounded if the agency can only reach banks in the short term," Barefoot said. "Then they'll spend their time reaching banks. So the banks will probably get more than their 'fair share' of scrutiny in the short term."

Not everyone saw a cause for alarm. Some observers noted that the CFPB is just picking up where the banking regulators left off, and non-banks currently aren't subject to any such oversight.

"In some ways, I think it just kind of maintains the status quo," said Jeffrey Taft, a partner with Mayer Brown LLP. "It doesn't necessarily change the playing field."

Still, Taft said that "over time, there could be an undue amount of focus on the banks."

Without a permanent director, the bureau is also likely to be directionless, and may hold off on any major rule writing initiatives, said Stacie McGinn, a partner at Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP.

"There's the old phrase no regulation is good regulation, so from the industry's perspective, the fact that they don't have a director means there may be inaction," McGinn said. "So maybe they'll get a breather in that regard."

On the other hand, that means less certainty for banks, as senior staffers will be reluctant to provide much detail on the direction of the bureau and its priorities, she said.

"At the end of the day, you've got to have a leader who's setting the course and the direction for the agency to function and be directive," McGinn said.