Banks are tightening underwriting standards on all manner of loans. They expect to do so even more in the case of a recession.

Lenders made it harder in the third quarter for both consumers and businesses to access credit, according to

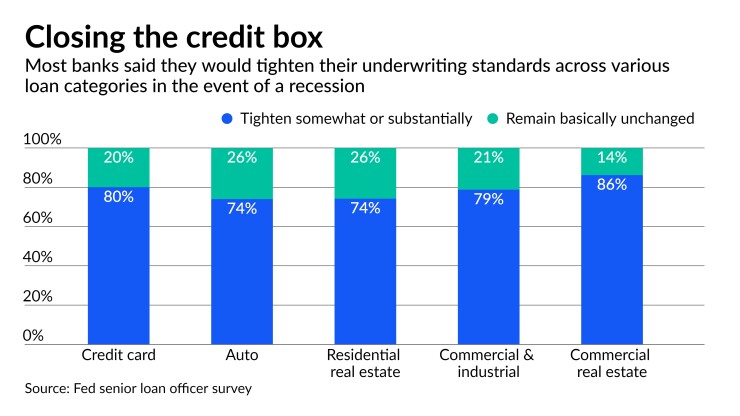

If the U.S. economy falls into a recession, more than 80% of banks said they would "somewhat" or "substantially" tighten lending standards for credit cards and loans backed by commercial real estate. More than 70% of banks said they would do the same for auto, commercial and industrial and residential real estate loans.

Lenders are concerned that an impending economic downturn could boost the number of bad loans on their books, which has made them more reluctant to approve new lines of credit. Asset quality, which improved during the earlier stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, has started moving back toward pre-pandemic levels, and banks are hesitant to take risks that could boost it higher.

"One of the times in which loans are at their riskiest is when they're unseasoned," said Megan Fox, a senior analyst at Moody's Investors Service. "The tightening of underwriting standards really reflects those concerns [of a recession]."

Most banks that took part in the Fed survey pegged the probability of a recession within the next 12 months at between 40% and 80%. The majority of those banks expect a "moderate" downturn, with none reporting that they expect a "severe" recession.

Lenders began tightening underwriting standards on most loans earlier this year. In 2021, many banks were making it easier for consumers to get approved for credit, easing requirements on credit cards and auto loans.

Among consumer loans during the third quarter, credit cards saw the most material tightening in underwriting standards, including higher requirements for income and minimum credit scores.

For borrowers with FICO scores between 620 and 680, banks reported being less likely to approve credit card and other loan applications last quarter than they would have been at the beginning of the year.

Consumers with higher credit scores saw less impact on credit availability than their counterparts with weaker credit scores.

"What you're seeing is a bit of bifurcation between types of consumer borrowers," Fox said. "Generally, prime homeowners are in good financial standing, and we're seeing the opposite on the lower-income or renter population, where there's perhaps more stress and less flexibility to absorb inflation."

Persistent inflation drove higher demand for credit cards in the third quarter. At the same time, rising interest rates and higher prices decreased demand for both auto loans and mortgages.

Meanwhile, banks reported more modest demand for commercial and industrial loans, especially from smaller firms. Demand for loans backed by commercial real estate, often seen as one of the riskiest asset types during an economic downturn, fell across all categories.

Demand for different credit products typically helps influence the tightening or loosening of underwriting standards. When demand for credit cards, for example, is low, lenders might relax their requirements in a bid to encourage more customer applications. When demand for mortgages skyrocketed in 2020 and 2021, lenders raised their minimum requirements and could reject candidates with less-than-pristine financial histories.

But the U.S. economy's precarious position has weakened that relationship. Now, lenders are relying more heavily on economic forecasts than on customer demand when deciding whether or not to extend credit.

The Fed's senior loan officer survey received responses from 71 large U.S. banks between the last week of September and the first week of October.