-

Iberiabank is among a handful of serial buyers of banks shuttering branches and taking other steps to lower expenses and raise earnings.

July 26 -

KeyCorp, which is still seeing expenses eat up more than two-thirds of its revenues, will cut costs and close branches in an effort to lower its efficiency ratio.

July 19 -

Discover has started originating mortgages after buying Tree.com's home loan unit, but executives say the lender will be slow and "sensible" about expanding the business.

June 19 -

Bharat Masrani is betting on branches at a time when many others are questioning their value. He explains why an aggressive U.S. expansion strategy — by acquisition and internal growth — makes sense for the Canadian-owned TD Bank.

June 7 -

Smaller banks are struggling to keep efficiency ratios down, forcing many bankers to look at closing more branches and laying off more employees.

April 25

Community banks are again swinging a wrecking ball at the bricks-and-mortar segment of their business plans.

Healthy institutions that include F.N.B. (FNB) in Hermitage, Pa., and Guaranty Bancorp (GBNK) in Denver, along with money-losing banks such as Anchor BanCorp (ABCW) in Madison, Wis., are shutting down a number of underperforming branches.

These companies and others are scaling back in an effort to

"Times are tough on the revenue side and people are trying to find ways to operate more efficiently," says Damon DelMonte, an analyst at KBW's Keefe, Bruyette & Woods.

Large banks, too, have announced plans to close branches this year. KeyCorp (KEY), an $86.5 billion-asset company in Cleveland,

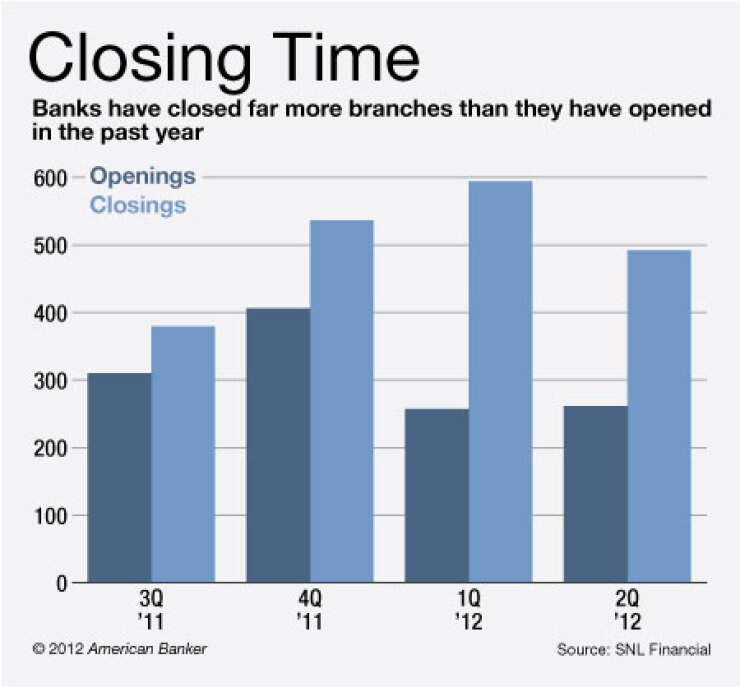

Banks have closed about 770 more branches than they have opened in the past year, according to data released Thursday by SNL Financial in Charlottesville, Va. The trend appears to be picking up steam, with several banking companies recently unveiling plans to shutter branches in coming months.

Acquisition activity has also prompted more branch closings.

Iberiabank (IBKC), a $12.1 billion-asset company in Lafayette, La.; the $4.1 billion-asset Home BancShares (HOMB) in Conway, Ark.; and the $2.4 billion-asset CenterState Banks (CSFL) in Davenport, Fla., opted to shut down branches after they bulked up on acquisitions and

Even with the renewed focus on the expense of operating physical branches, many banks aren't closing retail locations fast enough, says David Darst, an analyst at Guggenheim Partners. That's a mistake when companies with no retail presence, like Discover Financial Services (DFS),

"You're just not going to need the branch infrastructure to drive the same level of revenue," Darst says.

F.N.B., an $11.8 billion-asset banking company, plans to close 20 First National Bank of Pennsylvania branches later this year, while reducing service at three other locations. Each branch set to close houses an average of $16.5 million in deposits and $5 million in loans, Vince Delie, F.N.B.'s chief executive, said during a July 24 conference call with analysts to discuss second-quarter results.

F.N.B. also took into consideration a single branch's transaction volumes, production quality and other variables, when it decided on closings, Delie said. F.N.B. is bulking up online- and mobile-banking offerings to try to take advantage of "shifting consumer preferences," he said.

F.N.B. expects the closures to boost annual pretax earnings by $2.5 million to $3 million, Delie said. The closures represent about 8% of F.N.B.'s total branch network.

In general, a bank should close any branch with less than $20 million in deposits, Darst says. Banks often close branches with high balances from certificates of deposit, and the closures produce near-immediate savings. "Those higher-cost CDs are not relationship-based accounts, so you can lower your cost of funds quickly," Darst says.

Some banks

While some bank executives believe that they must maintain an extensive branch network to take advantage of loan growth when the economy rebounds, that line of thinking is a mistake, Darst says.

Instead of outright closures, another way to eliminate costly branches is to sell them, as the $22 billion-asset Associated Banc-Corp (ASBC) did during the second quarter. Branch closures are not "immediately imminent" at First Niagara Financial Group (FNFG), but the Buffalo, N.Y., company is taking a hard look at branches outside its core markets, said Greg Norwood, the $35.1 billion-asset company's chief financial officer.

"Some branches in our footprint aren't really in our strategy long-term view," Norwood said in an interview Friday. "To the extent it might make sense, we might sell those [branches] to other institutions."