Saving money is back in fashion, and banks are taking notice.

Since consumers are receiving little in the way of interest on their deposits and have become more conscious of meeting financial goals, banks are changing their tactics. Some, for instance, are using gift cards and other bonuses attached to savings accounts to reward customers for sticking to savings plans.

"We're trying to build features and benefits in the product that [are] going to make us stand out in the competition," said Theresa McLaughlin, group executive vice president and chief marketing officer at Citizens Bank, a unit of Royal Bank of Scotland Group PLC. "If it's just about rate, then the competition can match us."

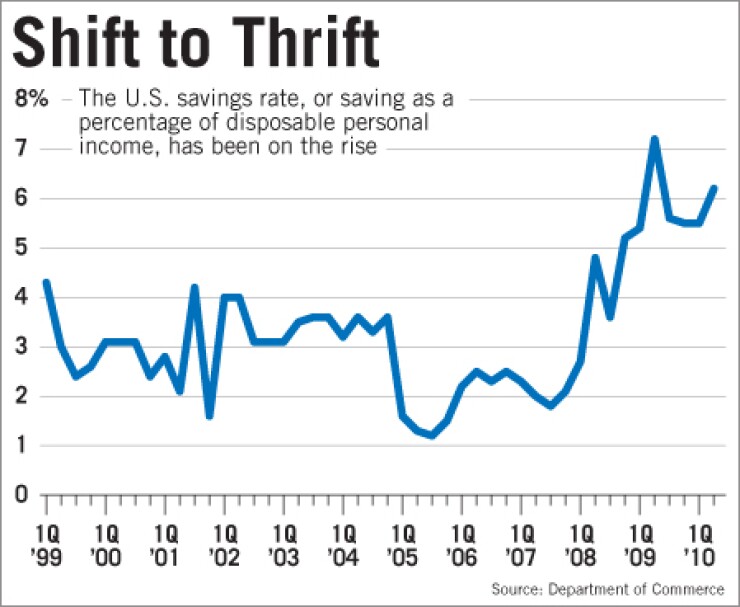

For much of the previous decade, saving wasn't a priority for most Americans. The average annual personal savings rate fell to as low as 1.4% in 2005 — the lowest level since the Great Depression. There was no pressing need then for innovative savings products, but the savings rate has been rising the past two years as the financial crisis forced people to rethink how they manage their finances. The personal savings rate currently hovers around 6%, according to the latest data from the Department of Commerce.

The shift toward a more penny-wise society is driving banks to turn their focus to helping consumers save and, in the long run, be more profitable customers. To be sure, some banks are trying to deter new deposits as they lend less. But offering tools to build savings creates opportunities for banks to cross-sell other products and helps offset some of the revenue hit they're taking from new restrictions on overdraft fees and other practices.

"Many banks are rethinking their business models," said Mark Schwanhausser, a senior analyst at Javelin Strategy and Research. Previously, "they benefited from the mistake of the consumer," he said, referring to revenue generated by overdrafts and other penalty-type fees. "This idea about aligning yourself with the customer and giving them the tools to manage their finances is the way to grow."

Consumers have been receptive. "The days of just borrowing on credit and thinking that [the value of] your home is going to go up and up and up, and that your 401(k) is going to double every seven years, are over," McLaughlin said. "Consumers are getting back to a place where borrowing is a part of their financial needs, but savings is becoming more and more of their need … and banks are responding."

Of course, with lending still down some banks have expressed concern over building up deposits too quickly. Margins can get squeezed if banks take in a lot more in deposits than they're able to lend. But savings accounts are generally seen as instrumental in attracting and retaining customers.

"Some institutions have kind of adopted an attitude that they're not quite as interested in more deposit funds at this time until lending picks up a bit," said Mary Beth Sullivan, managing partner at Capital Performance Group, a Washington consulting firm. "I think other banks are making loans and realize that there are opportunities to pick up additional customer relationships and the deposit side is where that's going to happen."

Jim Sinegal, an equity analyst at Morningstar, said that helping consumers save "is one way that the bank can get some of those deposits to stick around once the economy improves a little bit."

The appeal of a savings account has traditionally been the interest that could be earned. But with the Federal Reserve's benchmark interest rate (which savings rates tend to track) at a record low of near zero — and with no indication of it being raised anytime soon — making money on interest is tough to do.

"A high yield isn't all that high these days," Sullivan said. "I think Americans are, understandably, concerned about safety, security, and so, for most people, looking for yield in an interest rate environment like this isn't necessarily a priority."

U.S. Bancorp created a program called Savings Today and Rewards Tomorrow, or Start, because it "heard really clearly from customers [that] it's not about interest rates," said Trent Spurgeon, senior vice president of consumer products at the flagship unit U.S. Bank.

"It's about a meaningful reward, not as a reason to save, but as a pat on the back," he said.

Customers using the Start program have the option of scheduling the transfer of a specific amount of money at the same time every month from their checking to their savings account, or they can elect to have a specified amount, of up to $5, be transferred to their savings after every credit or debit card transaction. Account holders can also automatically sweep the cash-back rewards they earn on their credit card into their savings account.

Once customers reach $1,000 in savings, the bank will give them a $50 Visa-branded general-purpose prepaid debit card. And those who maintain a minimum of $1,000 in their savings for a full year after reaching the goal receive another $50 prepaid debit card.

The concept of automatic transfers is not new. But Spurgeon said the value of the Start program lies in its encouragement of consumers to reach their goals, as well as the rewards.

"If you look at it holistically, at every touch point from when you open the account to your statements to your online banking, all of these are reinforcements," he said. "You'll see how you're doing to reach your goal. It's also very unique that we reward you for maintaining your balance."

The program grew out of research the bank conducted in early 2009 to get a better sense of what consumers wanted from their bank. After polling more than 4,000 customers, "we found that they simply wanted to get back to basics," said Kevin Wright, U.S. Bank's vice president of emerging markets and segments management, at an industry conference in June.

Some 70% of survey respondents felt they weren't saving enough, and 60% of those polled wanted their bank to help them save more.

About one out of every three new U.S. Bank customers enrolls in the Start program, Spurgeon said.

Late last year, Citizens Bank started GoalTrack Savings, which helps customers save for everyday goals: a vacation, a car or simply a rainy-day fund.

Customers receive gift cards tailored to their specific goals once they are met. For example, if someone is saving up for a wedding, the reward might be a gift card from Bed, Bath & Beyond or another home-goods retailer. Citizens has created a formula that calculates the gift card amount based on the amount saved and the time it took to reach the goal.

The GoalTrack Savings program reflected the popularity of two more specific and longer-term savings programs the bank started in April 2009 — College Saver and Homebuyer Savings.

With the Homebuyer Savings program, customers set a dollar amount they'd like to save over a 36-month period.

If they save a minimum of $100 a month, they receive a $1,000 bonus at the end that can be put toward the closing costs on a mortgage at the bank.

The College Saver program helps customers save for their child's college education.

Customers who commit to saving a minimum of $25 a month, starting when their child is 6 (or earlier), can collect a $1,000 reward to be put toward books and other school supplies, when that child turns 18. The $1,000 bonus accrues interest from the time the account is open.

To give customers a bit of a cushion, Citizens allows them to skip one month of saving a year and still be eligible for the reward.

In a little over a year, 20,000 of these saving programs have been opened by both new and existing customers, McLaughlin said.

"These two products were hugely successful for us," she said.

U.S. Bank's Spurgeon acknowledged that financial institutions probably could have done more to help consumers save before the financial crisis, but without the demand, there was little incentive to do so. "We can build solutions, but if consumers don't want them or don't find value, then what's the point in bringing the supply?"

A handful of big banks added savings features to debit and checking accounts a couple of years ago, but they weren't as interactive as some of today's programs.

Perhaps the most prominent one has been Bank of America Corp.'s Keep the Change program, which rounds up purchases consumers make on their debit card to the nearest dollar, deposits that amount into a savings account and then matches consumers' savings up to $250 a year.

More than 12 million customers have been enrolled and more than $3 billion has been saved since the program was launched in October 2005, said B of A spokesman Don Vecchiarello.

(Other savings programs that have been around for a while include Fifth Third Bancorp's Goal Setter and Way2Save, which Wachovia Corp. created before its sale to Wells Fargo & Co.)

Analysts say the shift toward goal-setting, rewards-based savings programs reflects a bigger focus by banks on relationship-building. Helping consumers improve their financial position builds trust, and ultimately, loyalty, analysts said. Savings programs are also seen as a good way to bring younger customers through the door.

"The earlier the relationship starts, the better for the bank," said Morningstar's Sinegal.

PNC Financial Services Group Inc. had a younger demographic in mind when it created its Virtual Wallet program, which launched in June 2008. After a year of market research, the Pittsburgh bank found that saving was a priority for 18-to-34-year-olds.

Virtual Wallet is an online savings account and personal financial management tool that helps users set up and track financial goals. Unlike the programs at U.S. Bank and Citizens, this service doesn't currently offer rewards for reaching those goals.

Mike Ley, vice president of payments and e-business at PNC, said the bank is considering adding rewards, as well as other features, to enhance the program.