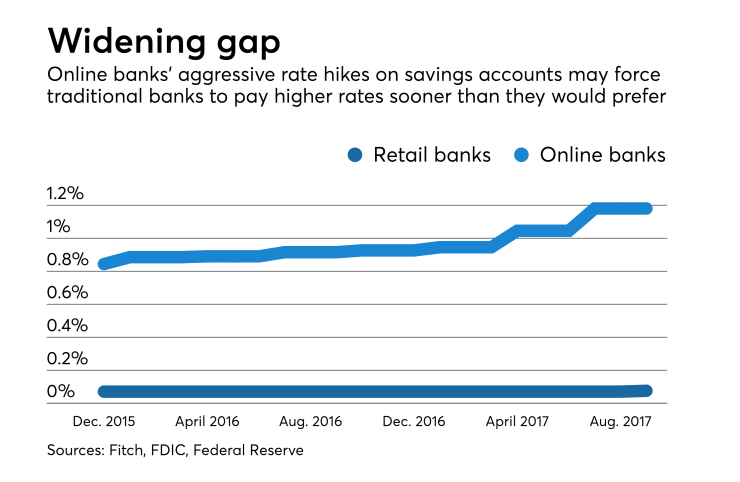

Online banks have been aggressively raising the rates they pay on consumer deposits, and that is putting pressure on mainstream banks to consider following suit or risk losing valuable deposits to their more nimble competitors.

A recent survey of 100 banks conducted by MoneyRates.com found that online banks such as Ally Bank, Goldman Sachs’ GS Bank and Sallie Mae Bank are paying significantly higher rates on savings and money market accounts than their brick-and-mortar counterparts. All had increased their rates during the third quarter, after the Federal Reserve raised benchmark interest rates in June — the third rate hike since late December.

The question of timing a hike in deposit rates is critical for traditional banks. If banks raise rates too soon, before their existing loans reprice to higher rates, their net interest margins could shrink and profits could suffer. But if banks wait too long, they run the risk of losing deposits to online banks that are paying better rates.

The average rate for savings and money market accounts at online banks stood at 1.18% in September, compared with 0.075% at traditional banks, according to a report released by Fitch Ratings early Wednesday.

Fitch estimated that if all U.S. banks with at least $50 billion of assets raised their average deposit rate to 0.75% — or 10 times what they are paying now — their total quarterly profits would decline by nearly 11% based on third-quarter earnings data. If the average rate was increased to 1.18%, their collective profits would fall by 17%.

"There’s an incentive to lag as much as you can" in raising deposit rates after a Fed rate hike, said Christopher Wolfe, managing director of financial institutions at Fitch. "But you need to remain competitive."

For banks that operate in multiple markets across the country, one way to lessen the hit to profits is to only raise deposit rates in specific markets.

The $29 billion-asset First Horizon National in Memphis, Tenn., for example, plans to test higher savings rates in Florida before raising them in its home market of Tennessee.

First Horizon, which has just one branch in the Sunshine State, will gain roughly three dozen more there this week when it closes its acquisition of Capital Bank Financial in Charlotte, N.C. Chief Financial Officer BJ Losch said in an investor presentation in November that Florida is a good testing ground for running new promotions because the bank has little name recognition there.

“Florida is a greenfield for us and … we expect that we’ll be able to do a lot of test-and-learn in raising deposits, figuring out what works from a direct mail perspective,” Losch said.

“Whenever we try to run promos or do something in Tennessee … we put at risk alienating existing customers to try to acquire new customers,” he added.

Of course, raising rates to attract new customers comes with risks, the biggest being that those customers could flee as soon as they find a higher rate elsewhere.

Executives at the $4.7 billion-asset Salem Five Cents Savings Bank in Massachusetts were well aware of such risks when they made the decision in October to raise savings rates at its online bank — but not its brick-and-mortar counterpart — to 1.5%.

Jay Spahr, the senior vice president of electronic commerce, said the bank had to raise its rates because loan demand has been outpacing its source of low-cost deposits. The bank’s loan-to-deposit ratio was 103.9% in the third quarter, versus 87.3% three years earlier.

“It would be great if we could have all our deposits come from core relationships, but right now our loan demand is outstripping the pace of deposit collection,” Spahr said.

Spahr declined to provide specific numbers on the amount of deposits that Salem Five has raised during its campaign. But he did say the program has been working to the bank’s satisfaction thus far. Salem Five reported total deposits of $3.4 billion in the third quarter, a 9% rise on a yearly basis and 1% in the quarterly comparison.

Still another option is to seek rate chasers by offering higher savings account rates on a national basis, but try to retain the new customers through service offerings. That’s the strategy that the $1.1 billion-asset Radius Bank in Boston is pursuing, said Chris Tremont, executive vice president of virtual banking.

Radius Bank raised its savings-account rate to 1.2% during the third quarter. Tremont declined to disclose specific figures on deposits collected from the rate promotion. According to Radius Bank’s call report, its deposits stood at $918.9 million in the third quarter, a 31% rise from a year earlier and 7% higher than the previous quarter.

Radius’ management believes that the bank can retain new customers obtained through the rate promotion, Tremont said. Radius has closed all its branches in the Boston area except one, and it now gathers most of its deposits through the online channel.

“The fact that we don’t have a large branch infrastructure means we can focus more on our customer experience and that plays itself out in the technology we’re able to build and the products we can offer,” Tremont said. “We’re out there trying to have people look at us as their primary bank account.”