-

With the release of Sen. Shelby's regulatory reform bill, the debate over the legislation is just beginning to take shape. We sort through the possibilities for how it will unfold.

May 12 -

GOP staff said the bill was intended to steer clear of provisions that would have automatically delayed or derailed the bill. But Democrats already were saying it went too far. Following is a complete guide to what's in the bill.

May 12 -

The Fed's annual dissection of each of the 31 largest U.S. banks is a painstaking and enormously complicated endeavor. This is an inside look at how it works.

February 27 -

Though stress tests are widely viewed as a successful and critical exercise, there are growing concerns that regulators and the banks themselves may have become too reliant on them, overshadowing other aspects of the supervisory process.

March 2 -

All 31 firms that took this year's Dodd-Frank Act Stress Test had enough capital to withstand the Fed's hypothetical severe economic scenario, but several of the largest banks were teetering on the edge of the leverage and risk-based capital requirements.

March 5 -

JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs were each forced to resubmit their capital plans in order to pass the Fed's CCAR stress test, while Bank of America was publicly faulted for weaknesses in its capital planning process. While some saw that as a bad sign, others contended the banks appear more comfortable in pushing the limits of the stress testing process.

March 11

As Congress considers reducing banks' regulatory burden, a key detail is missing from the debate: how much, exactly, do banks spend on stress testing?

Stress tests are arguably the most challenging postcrisis regulatory requirement, and the Federal Reserve's Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review process is the most intensive of all. It applies to banks with more than $50 billion in assets and is tougher for the largest banks.

There is no question that it is hugely expensive. For each of the biggest banks, the annual CCAR submission involves hundreds of employees collecting and analyzing a massive amount of data from the entire operation.

But concrete details on how much it costs are surprisingly scarce. And without more information on how much banks are spending, it is difficult to weight the costs and rewards of the stress-testing process.

Many observers think banks themselves may not know exactly what they are spending on CCAR.

"I don't know of a single bank that has told us the dollar amount of what CCAR costs," said Chris Mutascio, a Keefe, Bruyette & Woods analyst. "The costs for different regulations are so intertwined that I don't think they can say, CCAR is costing us X.'"

The CCAR process began in 2011 as a way to measure banks' capital adequacy in the event of another financial crisis. It has grown each year and now covers banks' internal processes for finance and budgeting, data gathering, risk and internal controls.

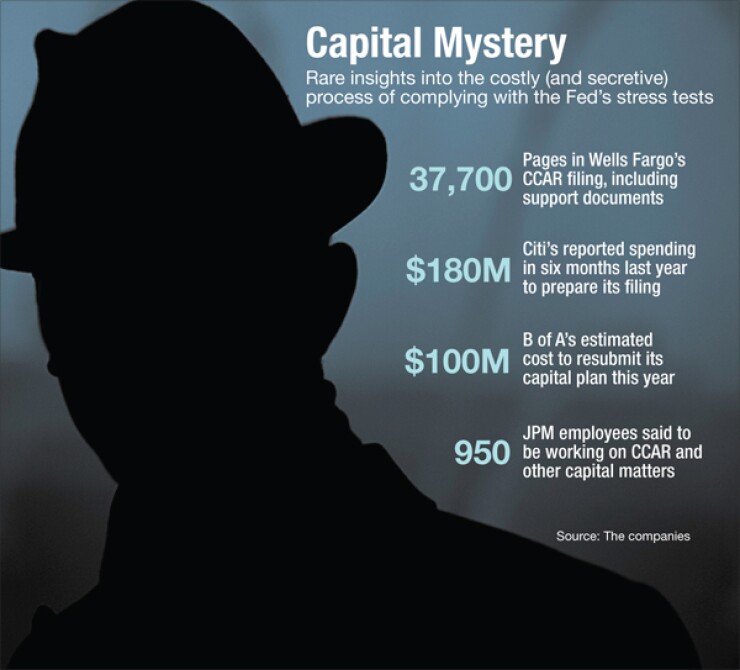

The amount of documentation and staff hours preparing the documents has grown as well. Wells Fargo's last CCAR submission was 3,700 pages long, accompanied by an additional 34,000 pages of supporting documents. Wells had 380 employees working on the submission, who logged an estimated 128,000 hours on the test in the fourth quarter alone, according to an internal company survey.

The process is rigorous, but has the benefit of strengthening internal controls, said Paul Ackerman, Wells Fargo's treasurer.

"In order to pull this off, you need to master data, modeling and writing, along with administering the whole thing, so that you have the entire staff working together," he said.

Others have questioned whether the benefits of stress testing are worth the expense. Senate Banking Committee Chairman Richard Shelby has also

Its costs have also become an issue in the debate over the $50 billion threshold for designating systematically important financial institutions, which subjects banks to CCAR as well as a host of other regulations. In the regulatory-relief bill he unveiled last week, Shelby

CCAR is likely the biggest single expense of crossing the SIFI threshold, but information on its precise costs is hard to come by. None of the 31 banks currently subject to the stress test have disclosed their annual budgets for the process.

The bank closest to hitting the SIFI threshold, New York Community Bancorp, has said it is

Banks have released limited figures after CCAR setbacks. Citigroup said it spent $180 million in the second half of last year preparing its successful 2015 submission after failing the year before. Bank of America said resubmitting its CCAR plan this year will cost an additional $100 million, but did not disclose its baseline spending on the process.

Other banks have offered broader numbers for what they are spending on compliance, without breaking out the cost of stress tests. HSBC Holdings, for instance, said it spent $2.4 billion on compliance last year, including CCAR, and JPMorgan Chase said it spent $13 billion on regulation from 2010 through 2014.

Some see an element of theater in the public disclosure of eye-popping compliance costs. Figures like Citi's $180 million and B of A's $100 million are "ballpark numbers meant to send a signal to regulators" that they are serious about improving their processes, said Mike Mayo, an analyst at CLSA.

The lack of information on costs is part of the wider problem of murkiness in the CCAR process, he said.

"The CCAR process is an enigma wrapped inside a riddle," Mayo said. "We don't have enough transparency from the regulators, and it's difficult to make sense of the numbers banks give us."

One reason for the lack of transparency around CCAR costs is the concern about releasing regulatory information. CCAR expenses are not confidential regulatory information that banks are legally barred from making public, but they are "part of the supervisory process, and banks just traditionally do not discuss the supervisory process," said Ernie Patrikis of White & Case, who is the former general counsel for the New York Fed.

Even if a bank wanted to discuss CCAR costs to explain to investors why its noninterest expenses are rising, for instance doing so can send dangerous signals about risk and internal controls. Disclosing costs "can draw unwanted scrutiny from the investing community and the regulators," said Larry Tabb of the TABB Group, a consulting firm.

Banks have been less reluctant to say how many people they have devoted to the task. JPMorgan has more than 950 people working on its capital planning, including CCAR, it said in its latest investor letter. Most banks have around one hundred to three hundred people working on their CCAR submissions, said Robert Stone, managing consultant with Experian Decision Analytics, which has consulted with many of the top banks' CCAR programs.

While a bank should be able to pinpoint the cost of submitting its CCAR exam, the process involves so much work across so many different parts of the bank that calculating the cost of the entire stress-test process could be nearly impossible. The stringent data-gathering, modeling and documentation requirements have forced banks to improve their internal systems, but these improvements benefit so many of a bank's operations that it is hard to attribute them just to CCAR.

"It's practically impossible for any bank to tell you what they're spending on CCAR because they probably don't know either," said Mayra Rodríguez Valladares of MRV Associates, a consulting firm. "How do you know if the dollar you're spending to upgrade the system is really for CCAR, or if it's for the Volcker Rule or to calculate another regulatory ratio?"

These huge investments have also had important benefits for banks, of course. CCAR has made banks better integrated, more aware of their risks, and in some cases more efficient.

Still, more cost-benefit analysis of CCAR and other regulations is "critically important," Patrikis said. And to do cost-benefit analysis, you need good information about costs which banks may not be able to provide about CCAR anytime soon.

"I don't think banks have a clue what it all costs other than that it's a whole lot of money and a lot of wear and tear on their people," said Will Newcomer, Wolters Kluwer Financial Services' vice president of finance, risk and reporting.