An awful lot of capital. Capital on top of capital.

These were just some of the phrases used last month by Jamie Dimon, the chairman and chief executive of JPMorgan Chase & Co., in describing the company's cushion for absorbing future losses. Citigroup Inc. executives sounded equally confident, telling investors on a recent conference call that the company is "one of the best capitalized large banks in the world."

There is little question that banks are in a better position than they were just a few short years ago.

But is more capital, or even an awful lot of capital, enough capital? And if so, what basis of measurement would one use to prove it? After all, the Tier 1 common ratio — the specific ratio that most big banks have been crowing about — only got plucked from almost complete obscurity two years ago. It was made the benchmark for a government-imposed stress test that may or may not have been contoured to the benefit of institutions that would have looked far worse by more widely used measurements such as tangible common equity ratios.

Given the equity raised and the assets shed since then, Diane Ferguson, head of banks in the Americas for Royal Bank of Scotland Group's RBS Global Banking and Markets business, said she thinks "banks generally speaking are OK now given what we know."

But it would be hard to say for sure, at least until the next big crisis hits. "What is strong enough? We've just been through the most intense crisis of any of our careers. It hit multiple industries. And so I think coming out of it, to ask that question is absolutely appropriate," Ferguson said.

Regulators have spent much of the past three years trying to arrive at an answer. Under recently announced Basel III rules, banks will have to show a 4.5% minimum common equity ratio by 2015, with an additional 2.5% capital conservation buffer required by 2019.

That's comforting insofar as it generally holds banks to a higher standard. But as the most recent crisis so sharply pointed out, regulators are not the only constituents with a vote in determining capital adequacy.

"I think for much of the history of banking, there has been a sense that regulatory capital exceeded economic capital, so there wasn't as much attention paid to the economic capital" required of banks to stay solvent, said Mark Olson, a former Federal Reserve governor and American Bankers Association president who now is co-chairman of Treliant Risk Advisors LLC. "But what this last downturn told us was that as more and different kinds of capital instruments or reserves were computed as a component of capital, the farther away we got from looking at the true economic need for capital. And I think the markets told the banking industry that there was going to be a much tighter standard for what was deemed as capital adequacy."

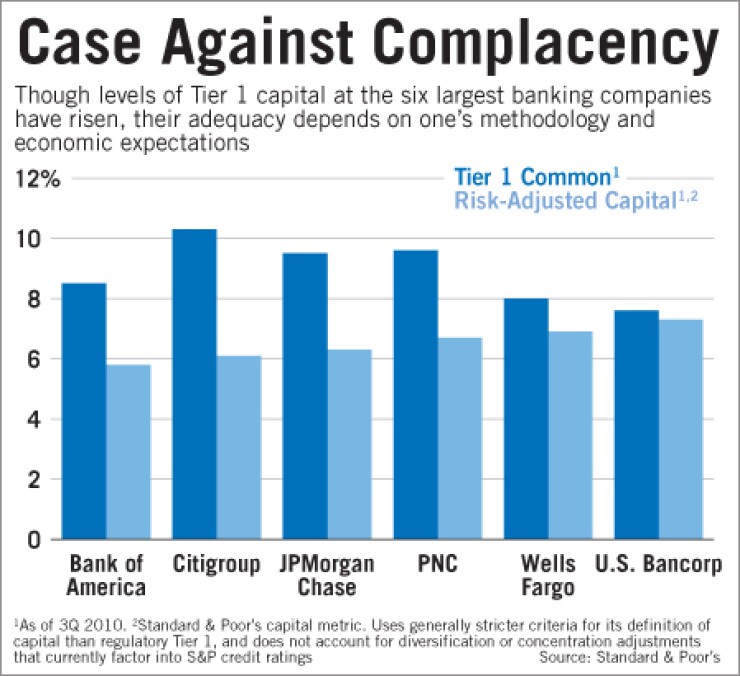

One of those voices is Standard & Poor's, which computes its own risk-adjusted capital ratio for banks. The RAC ratio, which gets factored into the credit ratings S&P assigns to banks, uses more stringent criteria than the Tier 1 common ratio. Under the RAC calculation currently used in determining ratings, Citi, which at the end of the third quarter of 2010 had a Tier 1 common ratio of 10.3%, had a RAC ratio of just 7.7%.

The disparity looks even greater against another RAC calculation S&P proposes to use as part of a broader set of changes to its ratings criteria for financial institutions. Under the new methodology, RAC calculations no longer would give banks credit for diversification or concentration adjustments in terms of geography, loan mix and exposure to specific customers. S&P proposes using the stricter RAC framework on the premise that the effects of diversification are amply captured by other factors in banks' credit ratings, such as their business position and risk position.

Without the diversification adjustment, Citi's RAC ratio as calculated by S&P drops to 6.1%. JPMorgan Chase had a third-quarter RAC ratio of 6.3%, compared with a Tier 1 common ratio of 9.5%; while Bank of America Corp. had a 5.8% RAC ratio, versus an 8.5% Tier 1 common ratio.

In a Jan. 18 report, S&P said that "despite a recent positive trend" in RAC ratios over the past two years, the firm is "of the view that banks' capital adequacy remains neutral to negative for our ratings on the large U.S. banks."

That's hardly a doomsday warning, but it does serve as a contrast to some of the headier discussions about dividend reinstatements, share buybacks and other capital-utilization strategies that bank executives spoke of during the latest round of earnings calls.

While regulators no doubt will be vigilant, the risk that banks get too far ahead of themselves in redeploying capital offsets at least some of the risk they eliminated shedding assets that were the most costly in terms of capital requirements. Meanwhile, new risks — social media? WikiLeaks? — are popping up all the time, said Bill Nayda, a principal at Second Pillar Consulting, a firm that helps banks comply with capital regulations.

"The ability for banks to look into a crystal ball, and for regulators to look into institutions and get a transparent view of the risks, is very difficult," Nayda said. "That's where you have to … have a pretty doggone good governance and risk-identification system within your institution to quickly bubble those risks up to the surface." It's either that, he said, or hold additional capital.