WASHINGTON – Banks are moving to defend the Federal Reserve's practice of paying interest to member institutions for their excess reserves held in central bank accounts in the face of mounting speculation that the practice will be a target of the next Congress.

A report

Wayne Abernathy, executive vice president of Regulation at the American Bankers Association, said the group is concerned that Congress might take aim at IOER when it convenes in January and committees start crafting legislation to revise Dodd-Frank. While he said there have not been any specific legislative proposals to date, the murmurs are significant enough that banks want to make sure lawmakers know how important the Fed's ability is.

"We have not seen significant congressional interest in trying to use the IOER interest payments for some sort of congressional project, but there has been occasionally enough chatter on the Hill that demonstrates that there's not really a full understanding of how it all works," Abernathy said. "Our experience is that when legislators don't fully understand something, that's when mistakes happen."

Bankers are fearing a redo of events in 2015, when Congress passed a

Since then there has been talk that Congress could see the interest payments as another source of quick cash, even though the payments don't really work the same way, Abernathy said.

"It looks like a pot of money, but when you reach out for it, it evaporates," he said. "But bad stuff happens in the process."

Aaron Klein, policy director of the Center on Regulation and Markets at the Brookings Institution, said the notion of looking to the Fed for a short-term cash infusion the first time was a mistake. Doing it again – particularly to meddle with IOER – would be disastrous.

"Congress using the Federal Reserve as a piggy bank full of budget gimmicks is a horrible idea that fails to tackle problems of deficits and creates problems in the real economy and for the Fed's independence," Klein said. "It is hard to think of a poorer policy choice for the next Congress to make."

The Fed's practice of paying interest on cash kept in member banks' accounts has a meandering legislative history. As a bank regulator whose primary original function is to manage and regulate the money supply, the Federal Reserve requires member banks to hold a certain amount of cash in accounts held at their regional Fed bank.

Those reserves received no interest, however, and banks had grumbled for years that the requirement that cash be held in essence under the Fed's mattress amounted to a tax. The effect was that banks stashed their excess cash in other places where they could earn even a nominal return – money markets, overseas or elsewhere. In the 2006 Financial Services Relief Act, Congress gave the Fed the authority to pay interest on cash held in reserve accounts, effective in October 2011.

For most of the Fed's history, its primary tactic for setting monetary policy had been to buy and sell Treasuries on the open market, primarily via the New York Fed. But when the 2008 financial crisis hit, there was no open market on which to buy and sell – the markets were essentially frozen, leaving the Fed little effective means of setting monetary policy.

Congress decided to include a clause in the Troubled Asset Relief Program bill that sped up the implementation of IOER from 2011 to 2008. Such a move both consolidated bank cash reserves under the Fed's umbrella and allowed the central bank to set a target federal funds rate by offering interest on bank reserves as well as a de facto interest rate via overnight reverse repurchase agreements.

Abernathy said IOER speaks to the legitimate purposes of both banks and the Fed: Institutions provide people a safe place to keep their money, and the Fed is empowered to keep monetary policy on a stable footing. By paying interest on reserves, banks can accept deposits they might otherwise refuse and the Fed can set rates more effectively, he said.

"There's still a reason why we have banks, and there's still a reason why we have the Fed, and IOER is … where those two institutions come together," Abernathy said. "By paying the interest on reserves you give banks a place to park deposits, and the banks by providing deposits creates an opportunity for the Fed to conduct monetary policy."

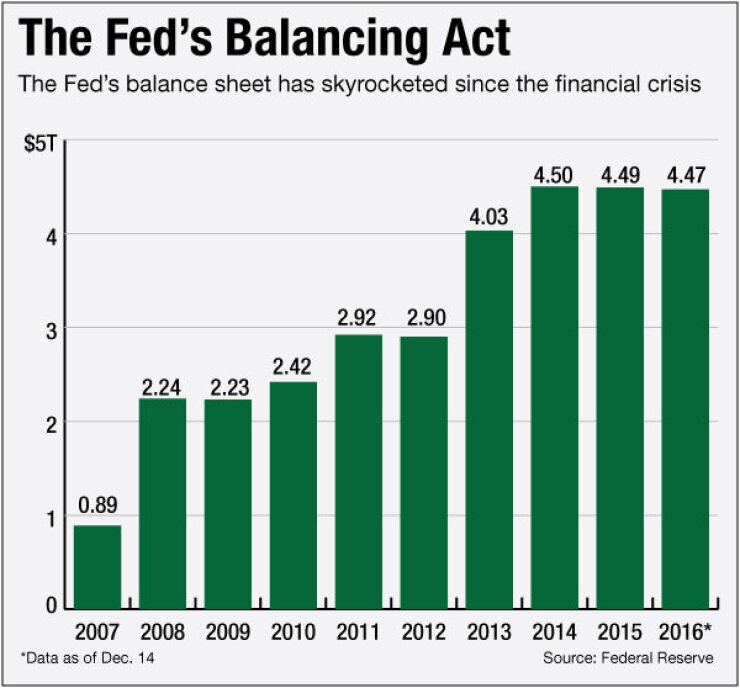

But there is a wrinkle. After the crisis, the Fed embarked on several rounds of so-called quantitative easing, in which the Fed purchased securities from banks in exchange for cash to shore up their balance sheets and spur them to lend. That caused the Fed's own balance sheet to swell to unprecedented levels; the Fed's assets top $4.4 trillion as of December 2016, up from roughly $830 billion in December 2006.

George Selgin, director of the Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives at the Cato Institute, said this application of interest on reserves – which was intended to eliminate the quasi-tax on reserve balances – as a tool of monetary policy is a departure from what Congress intended. He blames it for enabling the Fed to amass a towering balance sheet and says it effectively gives banks an incentive not to lend. What is more, the Fed's balance sheet artificially props up some securities markets at the expense of other areas of the economy where banks might otherwise invest, he said.

"I would say that interest on reserves is a much greater concern than it would otherwise be on account of the fact that the Fed's balance sheet is so large now … in relation to the overall quantities of credit in the economy," Selgin said. "What we have is a gigantic proportion … of the public savings intermediated by the Fed [directed] toward the particular securities markets that it has favored with its purchases."

Karen Shaw Petrou, managing partner at Federal Financial Analytics, said Selgin's line of reasoning is similar to arguments made by conservative lawmakers – that the Fed's balance sheet is the true culprit and it distorts markets.

"They're all very opposed to the Fed's portfolio because they think it unduly supports housing – that's been the most recent thread with the Republicans," said Petrou, whose firm published the paper on IOER. "With the Fed funds rate increase and the proposed two, maybe three, rises next year, there's just no question that this is going to be a major 2017 issue."

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen and the Federal Open Market Committee have said repeatedly that they are also concerned about the overall size of the Fed's balance sheet, and expect that they will be able to gradually wind down the central bank's position over time. Doing so too quickly could be highly disruptive, Abernathy said, potentially cratering Treasuries markets or otherwise creating unnecessary disruptions.

"I don't sense any desire to have a rapid reduction in the Fed's balance sheet," Abernathy said. "That would be incredibly destabilizing."

Just how likely this issue is to come up in the next Congress is unclear. Abernathy said the ABA has been attempting to educate lawmakers on the importance of IOER and has had some success in allaying their concerns, but "not enough to really put the issue to rest."

Klein said that in a normal political climate, Congress would trust the Fed to conduct monetary policy and give it the tools it needs to do that as effectively as it can. But this political climate is anything but normal, he said.

"All of the reasons why one should think this wouldn't happen – preserving the Fed's independence, not using the Federal Reserve as a gimmick piggy bank for Congress, and deference to the Fed's own ability to use the tactics it chooses to implement monetary policy – have come under attack," Klein said. "People shouldn't take things for granted."

Selgin said he is confident that some kind of legislative language limiting IOER will be included in the retooled Financial Choice Act – the Dodd-Frank revamp bill developed by House Financial Services Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling, R-Tex.

There are two basic designs for how that legislative might look, Selgin said: One would only allow the Fed to make payments on required reserves (not excess reserves) and the other would limit the Fed's ability to set IOER, favoring instead some other cash interest rate set by the market.

But others in the banking industry are not so sure. One banking industry official who spoke on condition of anonymity said the idea of tinkering with IOER is far more popular among House Republicans than it is among their colleagues in the Senate – and any Dodd-Frank reform bill has to make its way through both chambers.

The Trump administration, too, might be unlikely to support curbing IOER, particularly as the president-elect will have the chance to pick his own chairman in 2018.

"I don't get the sense this is on their actual target list," the source said. "The folks who were pushing that were Republicans, and now that we have a Republican administration, trying to seize the wheel like this would be kind of self-defeating."