The nationwide warehouse boom is slowing, but bankers still expect plenty of activity ahead as businesses seek to place industrial buildings closer to consumers expecting ever-faster deliveries.

The pandemic accelerated the years-long growth in e-commerce, fueling the construction and renovation of warehouses across the country. So many warehouses have been built in New Jersey that state and local officials have

The momentum is now easing a bit. Higher interest rates and rising material costs are making it more expensive to build new projects. Slower consumer spending on goods may necessitate less space for inventory. And one key driver of the warehouse boom — Amazon — is taking a step back after

But banks and industry experts still foresee significant demand for warehouses, which should give banks a steady source of commercial real estate loans for years to come. Demand is particularly strong among smaller companies that need less space, and for refrigerated spaces where retailers can store food for rapid delivery to customers.

Consumers' shopping patterns have shifted dramatically, and "Once a habit changes like that, it's tough to go back," said Chris Coiley, regional president for commercial real estate at Valley National Bancorp., a regional lender based in Wayne, New Jersey.

Some developers are taking a step back from warehouse projects as costs rise, and those who are proceeding with projects are due to make a bit less money, Coiley said. But the construction pipeline is "still very active," he added.

A shortage of available warehouses means rents are rising, and space is being snapped up quickly. Vacancy rates for U.S. industrial buildings fell to 3.1% last year, down from nearly 5% in 2020, according to a

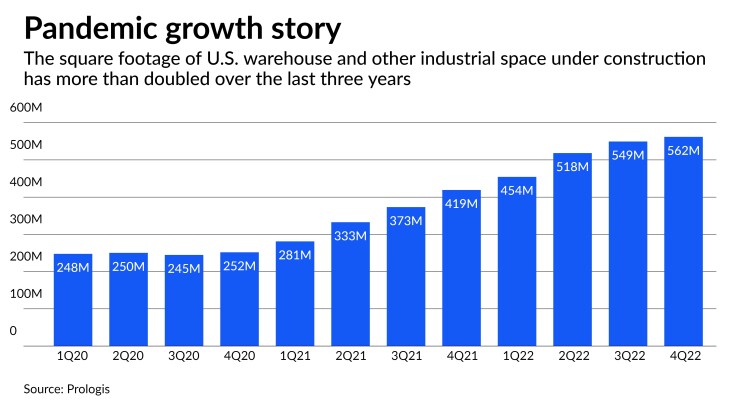

Though higher interest rates have slowed new construction, building pipelines remain far larger than in the past. Some 562 million square feet of U.S. industrial space were under construction at the end of 2022, up sharply from around 250 million square feet in 2020, according to Prologis.

The market is normalizing a bit after the "supercharged demand" of the last few years, said Lisa DeNight, director of national industrial research at the real estate firm Newmark. But "normalcy is still a very strong, active market," she added.

Richard Branch, chief economist at Dodge Data & Analytics, projected that warehouse building starts will likely return over the next five years to pre-pandemic levels, though those "were record levels" at the time.

The growth is leading to more business at banks of various sizes.

JPMorgan Chase, whose $3.7 trillion in assets make it the country's largest bank, said demand remains strong despite an apparent shift in favor of smaller buildings, rather than those needed by large retailers.

"Although rates and material costs have increased, increasing rents and strong demand have somewhat offset these issues," Al Brooks, head of the bank's commercial real estate team, said in an email. "While the market has slowed, strong developers are getting industrial deals done."

The market "should remain reasonably healthy for the foreseeable future" even if the U.S. enters a mild recession, Brooks added.

U.S. Century Bank, a $2.1 billion-asset bank in Miami, is seeing demand for "warehouses of all types," said Chief Lending Officer Nic Bustle. Customers are seeking large and small warehouses, dry-storage spaces, refrigerated warehouses and "flex spaces" that include both manufacturing and office space.

"At least here in South Florida, the economy seems to be very resilient, and demand is still there," Bustle said.

With interest rates rising quickly, Regions Financial is tightening its underwriting and taking a more conservative stance, said Weston Garrett, its head of corporate real estate.

Still, the Birmingham, Alabama-based bank isn't overly concerned about the possibility of those loans going sour, since low vacancy rates point to strong demand for warehouses and make it easier to find new occupants for empty space, Garrett said.

Regions, which focuses on the South, the Midwest and Texas, is seeing strong warehouse growth in many port cities. Warehouses near ports in Texas, Florida, Georgia and South Carolina are seeing "tremendous growth," Garrett said.

One apparent exception is the Los Angeles port, where the pandemic's supply-chain woes were evident in long lines of waiting ships. The area near the L.A. port faces a shortage of available land for warehouses, restrictions on new development and uncertainty due to

But the proliferation of warehouses has escalated in mid-size cities, said Newmark's DeNight. Both the bigger "first-mile warehouses" that are a short drive from large urban areas and the "last-mile" warehouses that are smaller and closer to consumers are enjoying growth, DeNight said.

In some markets, DeNight said, the current construction boom may lead to a bit of an oversupply. But there's still space for e-commerce sales to grow, along with a need for more modern warehouses, since a large chunk of the existing buildings are more than 50 years old.

"There's a lot of room for the market to grow just in playing catch-up to 21st Century inventories that can efficiently support modern supply-chain needs," DeNight said.