WASHINGTON — The banking industry mounted a massive and historic campaign against a Biden administration proposal for financial institutions to report new account flow information to the Internal Revenue Service.

For now, that effort — seen by some as the industry's largest grassroots campaign since the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis —

But opponents and supporters of the proposed measure agree that the fight is likely far from over.

“Nothing is done until a bill is officially declared dead or a bill is officially signed into law by the president,” said James Ballentine, executive vice president of congressional relations for the American Bankers Association. “So for our purposes, this is just the first quarter of the game.”

What distinguished the campaign mounted by bankers and their advocates against the reporting plan was the industry's involvement of their customers. In the years since the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, bank policy fights have been often fought on the margins of technical issues and regulatory relief. For example, the complexities of capital requirements like the

“Usually, banks don't involve their customers in political issues or policy issues,” said Paul Merski, executive vice president congressional relations and strategy for the Independent Community Bankers of America.

But a confluence of disparate factors seems to have created a perfect storm for consumer opposition. Having banks share a customer's account inflow and outflows with the government prompted fears about surveillance and a threat to data privacy.

“It became a privacy issue; it became a concern of the bank customers, not just of the banking industry,” Merski said. “That, strategically, was the turning point in the debate. This isn't just another regulatory mandate to report something — this was involving the relationship between the bank and their customer.”

Yet supporters of the plan maintain that another feature of the industry's lobbying campaign, as well as GOP arguments against the proposal, was a misrepresentation of the actual proposal.

They argue that industry representatives, lawmakers and in turn some consumers confused the issue by suggesting that the government would collect details about individual transactions. The actual plan, they say, boiled down to just two new data points: annual account inflows and outflows, much less than the depth of information readily available on a W-2 form.

“I actually am still a little surprised — maybe more than a little surprised — that the bank lobbies went so strident about it,” said Charles Rossotti, a former IRS commissioner who has supported the reporting plan.

“I mean, I never expected them to support a compliance requirement,” Rossotti said. “But I really did not expect a full-on political campaign. And I certainly didn't expect a campaign that was so strident and, in all fairness, just

Improving national tax compliance has been a major priority for the Biden administration. Since the spring, banks and other financial institutions were discussed as potentially playing a major role in that effort.

The original proposal was a nonstarter. It would require banks to report their customers’ annual inflows and outflows in accounts where such flows exceeded just $600 per year. A subsequent plan raised that threshold to $10,000, but the industry's opposition remained.

The administration estimated that the plan would be a significant revenue raiser, potentially collecting as much as $463 billion for the government over 10 years by strengthening the IRS's ability to catch wealthy tax cheats.

Even if the measure is ultimately not included in Democrats’ social spending package, it will likely be tempting for lawmakers in future legislative cycles to resurrect the idea as a way to offset potential budget deficits. The administration is still projecting revenue from investing in the IRS's tax enforcement capability, but that capability is weakened without the reporting requirements, analysts say.

“This issue is not going to go away,” said Isaac Boltansky, a managing director at BTIG. “It’s unclear whether there's any sum of money that can be thrown at the IRS to fix some of the issues and some of the avoidance schemes and some of the regulatory gaps that exist, which suggests this will not be the last time that we hear this proposal.”

“Legislative proposals don't die,” Boltansky added. “They just hibernate.”

'This proposal struck a nerve'

Advocates’ work against the plan began in May, when the Biden administration’s Treasury Department published its annual “Green Book” — a largely technical document outlining the government’s spending and revenue expectations for a given fiscal year.

A proposal in the Green Book to “create a comprehensive financial account information reporting regime” detailing “gross inflows and outflows” of customers’ financial accounts quickly caught the eye of bank advocates, who subsequently reached out to the Treasury Department for clarification on the plan. (Treasury did not respond to a request for comment.)

“We, like others, had conversations with Treasury to get a better understanding of what they were discussing. The more they discussed it with us, the more concerned we became,” Ballentine said. From there, the ABA and ICBA began to circle the wagons.

“We began to educate our members on this issue. As members became educated, the media started to pick up on the proposal,” Ballentine said. “As the media began to write on the issues, consumers became interested and aware — and this without us even reaching out to consumers. And then consumers started asking bankers, ‘Hey, what is this issue?’ "

The scale of opposition that followed is likely to leave a mark on the memories of lawmakers. Advocates say that the crusade against the IRS reporting plan may have resulted in more than a million cumulative messages sent to Congress.

One

“I've been involved in the banking industry for over 30 years, and you can really count on one hand the amount of times that consumers have actively gotten involved in a campaign,” Ballentine said. “This proposal struck a nerve.”

Robert Fisher, president and CEO of the $548 million-asset Tioga State Bank in Spencer, New York, said he was on a trip with his wife when she received a phone call from a personal contact raising concerns about the IRS reporting plan.

“It was from the lady who does our doggy daycare,” said Fisher, who chairs the ICBA board. “And the lady was like, ‘Hey, is this real? Are you really going to have to report this information to the IRS? And will it make a difference if I reach out and contact my congressman?' ”

“My wife basically told the lady, ‘Hey, this is very real. It’s not a fishing exercise, and you have to believe that reaching out to your member of Congress will make a difference,’ ” Fisher said.

Distrust of government and privacy concerns

One of the main themes of the campaign — and perhaps the most crucial for generating public opposition — was distrust in the government, specifically the IRS.

“Whenever the letters ‘I-R-S’ come up, people have questions,” Ballentine said. “And I think bank customers just had natural questions as to what type of information the IRS is seeking — that grew out of curiosity, and curiosity turned into concern.”

But Rossotti says that ingrained distrust of the government was exploited cynically by banks. Letters that the industry trade groups had prepared for customers, he said, suggested that the plan was meant to provide the government with all of a consumer's private banking details.

The proposal "was never that, and it certainly was not anything more intrusive than what 90% of regular taxpayers get," he said. "Every person that has a salary gets a W-2 that the IRS gets with 20 boxes on it and gives every detail about your earnings that goes into your bank account. Is that less intrusive than a summary report with two numbers?

“No, it's not, and [banks] implied that it was. It’s not that hard to put out confusing information for people who don’t follow things like this every day.”

Analysts agree that some bankers along with their

“As always happens in D.C., some of the arguments were conflated and aggrandized, like that your bankers were gonna spy on you. I think those were out of left field and probably unfair,” Boltansky said.

“But I found some of the commentary saying, ‘You want your banker to be a banker, not an IRS agent,’ to be compelling,” Boltansky said. “I think when we talk about any level of additional data collection, there are going to be concerns.”

Others says that concerns about how the proposed reporting regime would affect the level trust between bankers and customers were legitimate, especially for those who historically have been left out of the financial system.

“We heard quite a bit from our minority banks, Asian-owned banks, African American-owned banks, that their customers were concerned enough about this proposal that they would be reluctant to open up a bank account or drop their bank account, because they don't trust the government,” Merski said. “They don't trust the IRS.”

James Wang, president and CEO of Asian Bank in Philadelphia, compared the potential for distrust and confusion stemming from the IRS proposal to his immigrant and small-business customers’ discomfort with with currency transaction reports. CTRs, required whenever depositors withdraw more than $10,000 from an account at once, are meant to combat money laundering.

“Your typical small-business owner that is hardworking, filing their taxes — they already have a hard time comprehending, ‘Why do we need to file a CTR? I'm just conducting transactions,’ ” Wang said. “The customers feel like, ‘Well, everything I'm doing is legitimate, why would you need to collect additional information?’”

That kind of trust can be hard to repair once damaged, Wang said. “Our customers would not appreciate, when they put their trust and privacy within our care, that we had to then turn around and just hand that information over to the IRS.”

The shadow of distrust was magnified in part by technical ambiguities over how the IRS proposal would have worked in practice. By October, senior Treasury officials — including Secretary Janet Yellen — began to speak out more vocally in

But ultimately, the public never saw any precise legislative text that would have enacted the reporting regime.

Even as Democratic lawmakers floated a

“One of the first red flags on this was that it was this amorphous concept of financial institution reporting based on account flows, which is a big change from what usually you're doing” with IRS reporting, said Brad Thaler, vice president of legislative affairs at the National Association of Federally-insured Credit Unions.

Moreover, financial institutions say they’ve struggled for years to get a better sense of what law enforcement does with the myriad of reports financiers send to the government, such as suspicious activity reports.

“The government's already getting a lot of financial institution information, and one of the challenges we've heard about over the years is that there's never a report back to financial institutions or any clarity,” Thaler said. When financial institutions don’t know if their existing reporting is “even ever used, or to what degree that it's used, sometimes it just feels like they're doing paperwork for paperwork sake,” he added.

A 'very, very hard' reporting hole to fill

In spite of the widespread opposition to the plan and the government’s apparent decision to move on from it, few advocates expect that this will be the last time the public hears about this type of proposal. Treasury officials themselves have made clear that more robust reporting is a “

Earlier this week, during a panel discussion hosted by the Center for American Progress on tax compliance, Natasha Sarin, an assistant secretary for economic policy at Treasury, said that while it appeared the IRS reporting plan was off the table in negotiations amid the budget reconciliation process, “I hope to see it in a final package.”

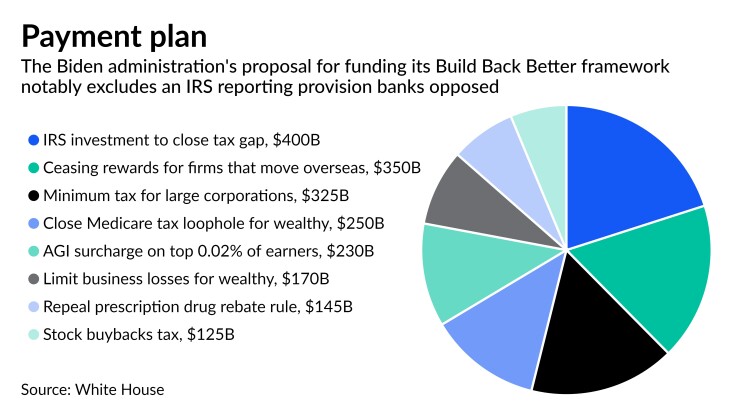

And even as the government appears to be backing away from the original scope of the IRS reporting plan, tax enforcement remains the single largest source of revenue contained within the most recent form of the White House's Build Back Better framework. Improved IRS tax compliance would generate $400 billion in revenue in the roughly $1.75 trillion spending package.

Bank lobbyists say they have no problem continuing to fight the IRS reporting plan, even if it continues to narrow in focus. Lawmakers appeared to briefly consider setting an income threshold — as opposed to a dollar flow-based threshold — of $400,000 a year before the plan appeared to be axed.

“There is no bad idea that ever goes away in this town. And whether it was in the infrastructure package, whether it was in a spending package, it was a bad idea,” said Ballentine. “It was a bad idea during the discussions of budget reconciliation, and it remains a bad idea today.”

Tax compliance advocates, meanwhile, warn that a financial institutions-focused reporting regime remains a compelling way for the government to begin to crack down on tax avoidance, and that bankers should tread carefully as their opposition persists.

“Certainly, if the whole thing falls apart and is never done, you are going to have a hole in the reporting regime which is very, very hard to fill,” Rossotti said.

“This is going to be viewed as a political victory for the bank lobbies, so they can take a victory lap,” Rossotti added. “But the question that you have to ask yourself is, was that a really wise move? To go all out, mischaracterizing this proposal — it certainly isn't going to win any friends among the people who really understand the issue.”