The Biden administration is eyeing banks as a resource to force wealthy Americans to pay more taxes. Banks say they aren't cops for the Internal Revenue Service.

A plan still in the early stages to expand the tax reporting that banks do on their customers' accounts — so the government can collect more on now-underreported investment and business income — has sparked a strong pushback from the financial services industry.

The administration wants to close the "tax gap" between what high-net worth Americans pay based on current reporting and what they actually owe. Many speculate this could mean an expansion of 1099 reporting for banks to provide account flow data that is now more opaque. A common 1099 form is submitted by banks with the amount of interest customers earn on their accounts.

But industry representatives and other observers say the idea — presumably to fund an infrastructure overhaul and the American Families Plan — would be a mistake. They say financial reporting is already robust, the expansion would prove costly and complicated for banks and their customers, and the benefits of expanded account flow reporting are questionable.

"This proposal will have real costs, not only for government, but also for financial institutions, small businesses, and individual taxpayers," several bank and credit union trade groups said in a recent letter to the Senate Finance Committee, which is exploring the idea. "Strengthening IRS funding to facilitate targeted auditing of questionable tax returns is a much more efficient and effective approach to closing the tax gap."

Some observers worry that expanding the reporting requirements could cause the IRS to receive more data than it actually needs, and damage the relationship between banks and their customers.

"We have to put the right protections on that data inside the IRS so it doesn’t burden taxpayers unnecessarily and cause a blowback to the financial institution," said Nina E. Olson, executive director of the Center for Taxpayer Rights.

Olson wants to limit the IRS's use of the data to sophisticated modeling for more targeted audits of wealthy taxpayers and not allow a new 1099 to be used as evidence that tax filers have underreported their income. An alternative approach puts the burden on the IRS, she says, not the taxpayer or the bank, to identify who should provide additional information.

The administration's plan represents the first serious effort in decades to collect taxes on underreported income from sole proprietorships, partnerships and other structures. Some have speculated that the administration aims to add new data entries on 1099 forms for bank account inflows and outflows for those types of entities.

“The President’s proposal would change the game — by making sure the wealthiest Americans play by the same set of rules as all other Americans," according to President Biden's American Families Plan. "It would require financial institutions to report information on account flows so that earnings from investments and business activity are subject to reporting more like wages already are.”

Any proposal also would need to include unregulated entities such as Venmo and PayPal, mobile payment apps and cryptocurrency exchanges, observers say.

But banking industry representatives say the plan basically amounts to deputizing the financial sector to help catch tax evaders, not unlike the compliance burden placed on the industry to crack down on money laundering.

"It’s really the IRS making the financial institutions the police force of reporting on everyone’s finances,” said Paul Merski, executive vice president and chief economist at the Independent Community Bankers of America.

The joint trade group letter said that policymakers should analyze the costs and benefits of expanding 1099 forms, that collecting more data would "require a new reporting paradigm for depository institutions," and that expanding resources for IRS audits is a better approach.

“We believe additional reporting requirements guided by subjective criteria have privacy and fairness implications and the potential to put financial institutions in an untenable position with their account holders,” the groups said. They included the ICBA, American Bankers Association, Bank Policy Institute, Consumer Bankers Association, Credit Union National Association, National Association of Federally-Insured Credit Unions, National Bankers Association, and the Subchapter S Bank Association.

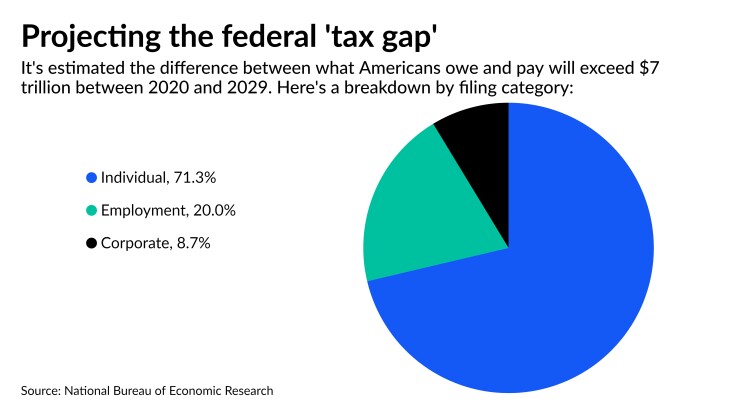

The projected federal tax gap from 2020 to 2029 is estimated to be roughly $7.5 trillion, according to a National Bureau of Economic Research paper authored by Natasha Sarin of the University of Pennsylvania and former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers. Up to 55% of income from high-net-worth taxpayers is unpaid because the IRS cannot identify opaque sources of income in partnerships, LLCs and S-corporations, according to the Treasury Department.

Experts said the Biden administration's plan would require banks — and potentially fintechs and other nonbanks— to generate a record of deposits and disbursements made by the top 25% of all tax filers.

The goal is for banks to provide information that would lead to more productive audits and aggressive debt collection while increasing voluntary compliance and deterring tax evasion.

The mechanics of providing such reports to the IRS would be similar to what banks already generate on 1099 forms for individuals with interest-bearing accounts, said Charles O. Rossotti, a former IRS commissioner.

"Every bank in the country has to report how much interest is earned on a bank account and they just run a computer program, that’s the same thing with this,” said Rossotti. In January he launched the website

“From a mechanical standpoint, it would be a very limited impact [on banks] with just two data points required,” said Rossotti. “You put [the data] in a computer program and run it once a year and that’s your obligation; there’s no judgment required, as opposed to [anti-money-laundering], which is very labor intensive.”

Others agreed that it is still early for banks to speak out against the plan.

“I’d like to hear from the bank IT people on just why this would be a big deal for the banks,” said James W. Wetzler, a former New York state tax commissioner and a former chief economist at the Joint Tax Committee.

But community bankers cite privacy concerns, and bank lobbyists claim the IRS currently has broad authority to access such data already.

“Turning over someone’s financial account information really goes way beyond any scope of complying with your tax liability," said Merski. "It’s basically opening up every bank or investment account for the IRS to look at. A lot of the time this closing of the tax gap is fools’ gold with banks doing all this onerous reporting and invading people’s privacy.”

But others counter that the IRS is extremely protective of taxpayer information and IRS leaks are extremely rare.

“The privacy issue is not a very persuasive reason to reject the proposal, because there are very rarely leaks of IRS information,” said Wetzler. “All the information anybody sends to the IRS is confidential and subject to secrecy laws.”

Perhaps the bigger issue is that the IRS appears to have a dual tax system, one for salaried W-2 taxpayers that has a high rate of compliance and another for sole proprietorships and small-business operators. The latter is seen as the biggest source of underreporting and tax evasion.

But because the effort to collect underreported taxes means primarily going after small businesses, it could face some political headwinds.

“There’s political support for dealing with rich individuals who don’t file their tax returns but I’m unconvinced there’s political support for cracking down on small business,” Wetzler said. “You’re starting to see that coming out in congressional statements.”

Rossotti testified at a Senate subcommittee on Tuesday that primarily addressed how much the government could raise by closing the tax gap.

A recent study cited by Treasury found that the top 1% of taxpayers failed to report 20% of their income and did not pay roughly $175 billion a year in taxes owed. But estimates vary widely.

“Once you figure out what compliance efforts are required of the banks and what burden that would be, you have to figure out how much the information would improve tax enforcement,” Wetzler said. "And that’s a very open question."

Meanwhile, banks would likely be doubly concerned if the plan applied only to them and not to unregulated nonbanks and payments apps that keep similar account records.

"Regulated banks have a very legitimate concern and our recommendation is that this is going to cover other entities including fintechs," Rossotti said. “We are trying to make this as mechanically simple a process as possible and to include anybody who has an account, not just at banks.”

Bankers have provided feedback to the Government Accountability Office on how to reduce the tax gap, and are in talks with tax experts on how to come up with a possible solution.

"We’ve been trying to talk to people that we know in the industry and make sure all of this is done to ensure it is the least burdensome on banks and taxpayers," Rossotti said.