Troubled debt restructurings are on the rise, and they're causing regulatory headaches for bankers worried about how to properly designate and disclose the modified loans.

Though regulators are encouraging banks to work with borrowers, bankers are wary of what they see as the not fully considered consequences. Specifically, they want assurances that examiners will not turn around and demand the restructured loans be classified. Yet even defining what constitutes a restructuring is proving difficult.

"There's been a learning process for some banking organizations, and I think that realization has really crept in and there is an interest to really do it right," said Julie Stackhouse, the senior vice president of supervision at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. "What we find, though, is, there is confusion."

Questions remain about how long the loans should be reported, how much a bank must reserve for them, which kinds of loans should be restructured and whether they are considered nonperforming assets.

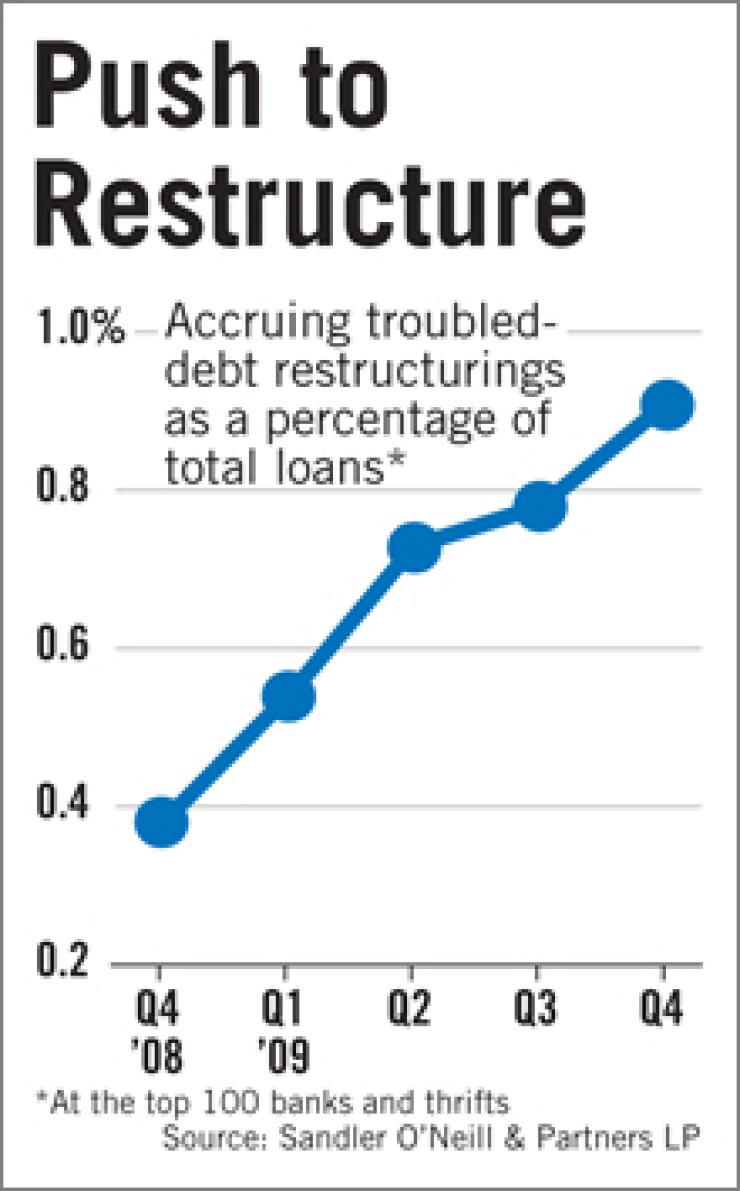

The issue has gained increasing relevance for bankers, examiners and investors as institutions increase their troubled debt restructurings.

The top 100 banks and thrifts significantly increased their accruing TDRs — restructured loans that are still accruing interest and being paid back — during 2009, according to a report from Sandler O'Neill & Partners LP. These loans as a percentage of total loans rose from 0.38% in the fourth quarter of 2008, to 0.91% in the fourth quarter of 2009.

Restructuring a loan by easing its interest rate or principal amount can make it easier for borrowers to afford their payments.

"Modifying these loans will increase the odds that they stay on a performing [status] longer," said Kevin Fitzsimmons, a managing director at Sandler O'Neill.

He said he expects the trend to accelerate as banks become more familiar with regulatory guidance issued in October.

The interagency policy statement encouraged banks to work with borrowers, especially those who continued to be creditworthy and demonstrate a willingness and capacity to repay the loan. "The regulators are really trying to motivate the banks to take the proactive action," he said.

Scott Kingsley, the chief executive officer of Community Bank System Inc. in Dewitt, N.Y., said his $5.4 billion-asset company is more apt to work with borrowers who experience a temporary disruption of their cash flow yet are likely to recover. Giving them relief is often in the lender's best interest, he said.

"The real risk is somebody handing you the keys back because, at the end of the day, we don't want the assets," Kingsley said.

Though TDRs can be beneficial, they run a significant risk of falling into default again and often are classified by regulators, said Kip Weissman, a partner in Luse, Gorman, Pomerenk & Schick. An increased level of classified assets could then prompt an informal agreement or enforcement action.

"We see this all the time," Weissman said.

Consensus also is scarce among bankers and examiners on whether TDRs should count as nonperforming assets. The decision to include or exclude TDRs from this category could have huge implications for a bank's Texas ratio — and, in turn, its viability, Weissman said.

For example, he said, a bank with a 3% ratio of nonperforming assets to total assets and an additional 3% of TDRs to total assets may consider only its nonperforming assets a problem.

"If the regulators accept that, then that bank's probably OK," he said. "But on the other hand, if the regulators view the [TDRs] as nonperforming, you could literally be looking at receivership, or certainly a consent order. So that's where the rubber meets the road these days, and it hasn't been resolved."

Banks also struggle with which loans to designate as troubled debt restructurings in the first place.

The October interagency policy statement said a restructured loan is considered a TDR when the institution grants a concession to the borrower for economic or legal reasons related to a borrower's financial difficulties.

Yet designating a loan change as a concession is often a subjective decision, said Dorsey Baskin, a partner in the professional standards group at Grant Thornton LLP.

Though many banks designated modified loans as TDRs during the economic downturn in the early 1990s, most no longer have a systematic way to identify them, Baskin said.

"Now, one of the tasks is to have a process in place and good controls so that the bank identifies the TDR, rather than the auditor and the examiner, because then it may be an indication of a control deficiency," he said.