Professional athletes may at times seem superhuman, but they need banking services just like everyone else.

Often, pro athletes face unique obstacles obtaining credit to buy a house or start a business, creating a need for expert financial advice.

For banks, successfully courting those clients is far from a slam dunk. Lenders must hone certain skills to build relationships, from recruiting prospects to developing an in-depth understanding of complicated contracts.

If mastered, the business could benefit banks that are searching for lucrative niches in an industry where many products have become commodities and a growing number of services are subject to intense competition.

“Lending to professional athletes can be a great opportunity as long as your eyes are wide open,” said Clay Gaitskill, a managing director of wholesale commercial credit at KPMG. “It takes some diligence, especially for banks that don’t have an established high-net-worth group that specializes in this.”

Accessing credit can be challenging, especially for younger athletes who have just signed rookie contracts. In many instances their credit history or assets may be scant, said Leon McKenzie, founder and president of Sure Sports Lending, a firm that provides financing to players and works with a network of roughly 175 banks nationwide.

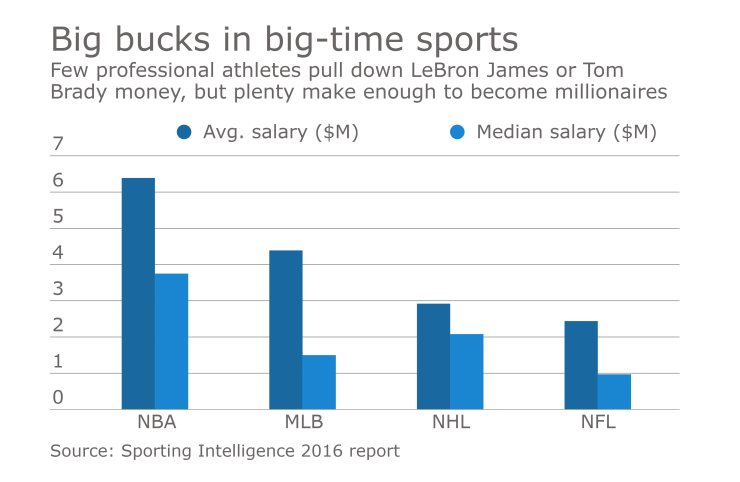

Those customers could still be attractive to banks. McKenzie notes that only a handful of players on a standard 53-member professional football roster are superstars with big contracts, adding that the “other 48” represent an opportunity for financial firms.

Many lesser-known players still make high-six-figure salaries, and some can top $1 million, McKenzie said. Those athletes need wealth management or private-banking services to help manage their funds, or they may want advisory services or loans to start a business. Athletes often want to buy houses for themselves or for family members.

Sure Sports, which also offers its own lines of credit, uses an athlete’s contract as the primary asset for underwriting, McKenzie said. Loans are usually short term in nature because they run the length of a contract. The firm will lend against 30% of a guaranteed contract — and up to 10% of a nonguaranteed contract — but it will also offer loans to free agents who are in between contracts.

Banks often set up their own parameters based on risk appetite, McKenzie said.

Developing relationships with athletes is a critical component of the business, said Tom Hall, president and CEO of Resurgent Performance, an advisory firm. That way the lender gets a more holistic view of the athlete's finances.

“You want to be the trusted adviser,” Hall said. “You have so many people vying for the athlete's attention.”

That is KeyCorp’s strategy as it works with professional athletes, said Pete Dunbar, a senior relationship manager at Key Private Bank in Indianapolis. The bank doesn’t actively solicit football, basketball and hockey players. Rather, it meets prospects through business managers or professional sports agents. The Cleveland company also works with Sure Sports.

“We prefer to work with athletes that have ties to our local markets,” Dunbar said. “That’s so we can have a broader relationship beyond just making a loan. We want to advise the client over a lifetime.”

There are risks involved with lending to professional athletes. It is always possible that a promising player will fizzle in the pros or that a rising star’s skills quickly and unexpectedly erode.

Player contracts can also be terminated if they grab headlines for off-field issues, though such instances are rare. The Baltimore Ravens, for instance, voided the contract for star running back Ray Rice following a very public case of domestic abuse.

Players with guaranteed contracts are still paid even if their ability diminishes, industry experts said. To cover instances where a contract is voided, lenders can buy insurance that will pay out if something happens.

Banks willing to lend money to pro athletes may need to be flexible with some underwriting criteria. For example, various leagues pay players differently — teams in the National Football League pay players only during the 17-week season, while National Basketball Association franchises distribute checks 24 times during the year. These differences can influence a player’s cash flow and, by extension, the structure of a loan.

Banks may also face reputational risk, Gaitskill said. Professional athletes often have big followings on social media, which could create headaches if they go online to complain about a bank experience.

That's why it's crucial for a bank to develop expertise before diving in, industry observers said. Banks that opt to work with a third party to help underwrite loans and recruit clients should conduct thorough due diligence.

From time to time KeyCorp will take extra steps to make sure it is repaid, Dunbar said. For instance, the bank could require an athlete to maintain a minimum deposit relationship.

“Our goal is to be able to tell the KeyBank story,” Dunbar said. “That’s why we only work with athletes who are concerned about long-term goals and want financial success and prudent investments.”