-

Banks, especially small to midsize ones, have been rewarded with strong loan growth this year. But heavy competition and uncertain economic forecasts are forcing them to keep fine-tuning their growth strategies, asset mixes and risk tolerance.

August 1 -

Most bankers expect to see deposits flow out of their coffers next year if interest rates rise as expected, and some are starting to estimate how many. Whether the trend is good or bad depends on each bank's specific situation, but everybody has to get ready.

July 30 -

Interest rates for mortgages over $417,000 have fallen 11 basis points during the past six weeks, driven by competition among banks to win the mortgage business of wealthy, less risky borrowers and in turn, make them customers of other financial products.

July 29 -

It sounds liked a great business formula: home loans soared at several megabanks last quarter after they spent months cutting thousands of jobs to save costs. But executives remain concerned about profit potential because market shifts and new regulations are making mortgage lending more expensive.

July 25 -

Banks are preaching the importance of getting low-cost deposits on their books now, ahead of new Basel liquidity rules, and the impending rise of interest rates.

February 14

It's the topic everyone in banking can't stop talking about in private, but which seems to touch a raw nerve when broached in public the

One reason is that some banks are better positioned than others to minimize the damage or even capitalize on it.

Deposits are widely expected to run off in droves in the second half of 2015 because the Federal Reserve is slowing its bond purchases and is expected next year to raise short-term interest rates.

The situation could produce a massive loss of liquidity; Marianne Lake, JPMorgan Chase's chief financial officer, in June predicted banks could see $1 trillion of liquidity losses.

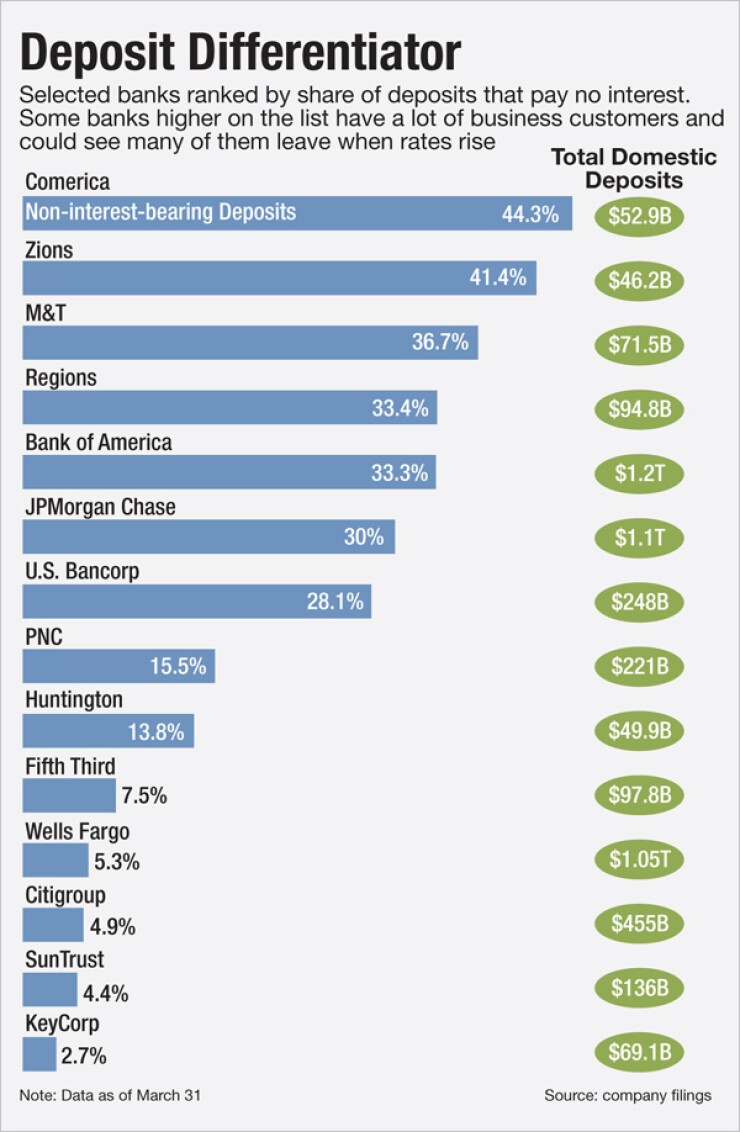

Some banks could fatten their net interest margins depending on what they pay for deposits now and if they can minimize runoff. But others, like Comerica and Zions Bancorp., whose non-interest-bearing deposits make up more than 40% of their U.S. deposits,

could be more vulnerable than others to missing that opportunity.

"The risk of deposit outflow is less about a true liquidity shortfall and more about the risk of higher funding costs, as banks could be forced to replace relatively cheap deposits with higher-cost funding," Bill Carcache, an analyst at Nomura Securities, wrote in a July 30 research report.

At the highest levels of banks' corporate ladders, deposits apparently are the prime topic of conversation.

"As you can imagine, [the rate of runoff in] deposit[s] is a rich discussion that we have maybe daily at the company," William Rogers, the chairman and chief executive of SunTrust Banks, said during a July 21 conference call.

So while most expect big deposit outflows, predicting who is most vulnerable to a loss of cheap deposits is complicated. The problem is that it's not easy to outline a direct cause and effect, said Brian Foran, an analyst at Autonomous Research.

"In terms of translating deposit runoff, one for one, to deposit costs, it's tricky," Foran said.

The industry as a whole has brought its deposit costs way down. Time deposits, which are more expensive, as a percentage of total deposits industrywide, have fallen from 45% in the first quarter of 2009, to 28% in the first quarter of this year, Carcache said.

But banks vary in their mix of customers, specialties and histories, so there isn't one telltale statistic that can determine which banks are most at risk, Foran says.

Some banks' business models have traditionally produced a large base of low-cost funding, and have always had a lower cost of funds, even before the economic crisis.

"If you've always had 40% non-interest-bearing deposits, like Cullen/Frost [Bankers], that's not a bad thing," Foran said.

But some banks just arrived to the party. Comerica, for example, has grown its cheap holdings faster than anyone, Carcache said. Comerica's non-interest-bearing deposits, as a percentage of U.S. deposits, rose from 8.3% in the first quarter of 2009, to 44.3% in the first quarter of this year.

Some other banks have also seen their levels of low-cost funding shoot up, including M&T Bank and Huntington Bancshares, Foran said.

"If it's gone up a lot in past years, you say to yourself, 'Whoa, why did that happen?'" Foran said.

M&T Bank's level of non-interest-bearing deposits rose from 8.7% in the first quarter of 2009, to 36.7% in the first quarter of this year. That move can largely be explained because of M&T's November 2010 acquisition of Wilmington Trust, which added a large number of high-net-worth clients.

Huntington's rose to 13.8% from 3.5% over the same period, because its deposit base shifted from a consumer-focused model to more business banking, Foran said.

Banks will want to hang on to those cheaper deposits when rates rise. But some are more vulnerable to losing those deposits.

Both the $65 billion-asset Comerica, in Dallas, and the $55 billion-asset Zions, in Salt Lake City, emphasize corporate and business banking. But corporate customers have the least brand loyalty and are most likely to yank deposits to get a better rate elsewhere, Carcache said.

In Comerica's earnings conference call for the second quarter, CFO Karen Parkhill said its deposits would decline and that it studied scenarios in which they fell as much as $6 billion, or 11% of its domestic deposits. But Parkhill said the company was nevertheless well positioned. Comerica has

"We did provide some sensitivity scenarios of what if deposits decline more, what if pricing increases more than it has over history, what if loans grow faster, what if rates rise faster," Parkhill said. "Depending on those varying assumptions, we showed that we are still very well positioned to benefit when rates do rise."

Parkhill was not available for additional comment, according to a spokesman.

Zions is also vulnerable because it holds a large proportion of low-cost deposits and corporate customers are a big piece of its client base, Foran said. As of March 31, about 41.4% of Zions' $46.2 billion in U.S. deposits were non-interest-bearing.

Even so, Zions has declined to provide a specific estimate of how much it expects in deposit runoff. During its July 21 earnings conference call, CFO Doyle Arnold deflected several questions about deposit runoff.

"If you want to refer to somebody else who's in tune with our thinking, I'll refer you to the CFO of JPMorgan Chase, who laid out pretty explicitly what she thinks is going to happen," Arnold said, referring to Lake's prediction of the $1 trillion of deposit runoff.

James Abbott, director of investor relations at Zions, cautioned that it's very difficult to predict what will happen with its deposit base.

"We'd be the first to tell you that we don't know how the deposits will react in the rising rate environment that we appear to be going to experience," he said.

Zions expects that it will see higher rates of deposit runoff, because of its concentration of commercial customers, and that it may see its low-cost deposits replaced with higher-cost deposits, Abbott said. However, these issues are true for any bank in this situation.

"This isn't a Zions problem. It's a problem for anyone who's got a commercial deposit base," Abbott said.

Like Comerica, Zions is also predicting that it will see an improvement in its bottom line. Zions estimated that its net interest income would rise between 15.1% and 17.8% during the first year that rates rise, if they rise by 200 basis points.

But Arnold and the other Zions executives certainly had been expecting to be queried on deposits since it is a hot topic.

"We debated about whether to talk about deposits in the opening remarks or wait for the question," Arnold said, which was met with laughter in response. "That's our No. 1 question."