When Harris Simmons was a small boy, he asked his father, Roy, the longtime chief executive of Zions Bancorp. in Salt Lake City, to explain what he did for a living. “We take money from some people and give it to other people,” Roy told his son, whose mind started racing.

“I was just certain he was going to go to jail for that,” Simmons recalled with a laugh during a recent interview. “I remember my shock.”

But it didn’t take long for the younger Simmons to figure out how banking works. He got involved at Zions early on, taking a job there in 1970, the week after his 16th birthday, filing canceled checks. As an undergraduate at the University of Utah, he was splitting his time between campus and the bank.

At age 27, he became chief financial officer. Nine years after that, he was named CEO, succeeding his father.

“I grew up learning the banking business from my father — at his knee, if you will,” Simmons said.

In his nearly three decades at the helm, Simmons has applied his analytical mind to an industry that looks far different than it did during his father’s era. He has repeatedly demonstrated an ability to see around the next corner, a strong grasp of the operational side of banking, and a determination to play the long game.

Because of that rare combination of traits — which are evident in three bold moves Zions made recently — American Banker is honoring Simmons as its Banker of the Year for 2018.

After taking stock of the changing demands of regulators and the rise of digital banking, Simmons decided to rethink Zions’ decentralized business structure. He later took the streamlining a step further by shedding the consolidated bank’s holding company. Simmons also launched a massive technology project, unmatched by any other large U.S. bank, to modernize Zions’ core processing system.

“He’s a leader that leans into the really tough decisions,” said Scott McLean, Zions Bancorp.’s president and chief operating officer.

Deep roots in Utah

Harris Simmons was 6 years old when his father led an investment group that purchased a majority stake in Zions First National Bank. It was 1960, and for more than eight decades, the bank had been controlled by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Sitting inside his second-floor office in downtown Salt Lake City, Simmons narrated a history of the connection between his bank and his church. He noted that following the migration of Mormons to Utah in the mid-19th century, their leader, Brigham Young, needed to figure out how to start an economy.

“He was a very entrepreneurial individual, of necessity,” Simmons said.

Young started two banks in the early 1870s. Zions Savings Bank and Trust Co., the second one, was created in 1873 to provide competition for the first. Today, the organizational documents for the bank that was Zions Bancorp.’s earliest forerunner are on display in Simmons’ office.

Simmons’ father overcame a rough start to rise to prominence in Utah. He was given up for adoption as a baby, and after his adoptive mother died when he was 8 years old, he was sent to live with a family friend in Salt Lake City.

Roy Simmons entered the banking business in 1940 — working for his father-in-law, whose family had started the First National Bank of Layton, located in a small city about 25 miles north of Salt Lake City. He went on to serve as state banking commissioner from 1949 to 1951.

Later, he operated the Lockhart Co., an industrial loan company that carved out a lucrative business by taking advantage of certain regulations that restricted banks’ activities.

Specifically, Lockhart was able to pay higher interest rates on deposits than banks could, and it used those deposits to fund the second mortgages it offered — a revenue stream that was shut off to banks at the time.

When Roy Simmons became CEO of Zions in 1964, the bank was smaller than two other Utah competitors, and it was focused on the Salt Lake City market. He set out to build a statewide franchise.

“So my dad started to do acquisitions, ultimately from St. George up to Logan, across the state,” Harris Simmons said. As he reminisced, he pointed to a portrait of Roy Simmons that hangs in the hallway just outside his office door.

Roy Simmons died in 2006 at age 90. In

Friends and colleagues say much the same about the son who followed him into the banking business.

Interstate and digital pioneer

As a young man, Harris Simmons served on a two-year church mission in Sweden, got an MBA from Harvard Business School and did a short stint at a bank in Houston. But by the early 1980s the low-key banker was back in Utah.

Soon he saw an opportunity to grow Zions by crossing state lines — a novel concept at the time. “Harris saw, very early on, the future of this,” recalled H. Rodgin Cohen, an attorney at Sullivan & Cromwell who has done work for Zions over several decades.

Before a change in federal law in 1994, a bank could acquire an out-of-state depository only if the two states had entered into compacts that allowed for such deals.

Zions played a pivotal role in persuading lawmakers in the neighboring Silver State to pave the way for its 1985 purchase of Nevada State Bank. One question that Zions had to answer was whether a bank with a deep historical connection to the LDS Church would be willing to finance the gaming industry.

In fact, Zions had been financing casinos near the Utah-Nevada border for some time. “So it was like, been there, done that,” Simmons recalled.

After the Nevada acquisition, Zions expanded into Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, Washington and Wyoming.

Simmons also showed foresight with respect to the impact that technology would have on the banking business. In the late 1990s, long before the first smartphones were in consumers’ pockets, Zions emerged as a pioneer in the remote deposit of checks.

In recounting that chapter of the bank’s history, Simmons credited Danne Buchanan, who was then the chief information officer at Zions, with having an idea for how to clear checks electronically.

“He said, ‘I’ve been thinking about an approach that on the surface doesn’t seem very elegant, except that it works,’ ” Simmons recalled.

Under this early concept, a bank would take pictures of the checks it received, and then send those photos to the payer’s bank, which would reproduce a paper copy of the check. Unfortunately, the process would not be all that useful unless federal law were modernized.

Simmons met during the summer of 2001 with Roger Ferguson, then the vice chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, in an effort to sell the concept. The meeting was pleasant, but the idea of clearing checks electronically did not appear to be high on the Fed’s agenda.

Then came the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, which led to a temporary halt in air travel, grounding the planes that the Fed used to ferry checks across the country.

“About three days later, we received a call from the Federal Reserve saying, ‘We’d like to talk again,’ ” Simmons recounted. The law known as the Check 21 Act was enacted two years later.

“It actually took 9/11 for them to understand we have a weakness in the payment system,” Simmons said.

‘A very taxing period of time’

In March 2000, Simmons experienced what he remembers as the biggest disappointment of his career, when Zions’ proposed merger with First Security Corp. fell apart.

The deal, which was billed as a merger of equals, would have offered Zions an opportunity to expand in western states, while also consolidating operations. “So the math of it looked reasonably compelling,” Simmons said.

But the acquisition hit a snag when an accounting issue drew attention from the Securities and Exchange Commission. That led to the postponement of the meeting where Zions shareholders were scheduled to vote. During the delay, First Security issued a disappointing earnings report, and its share price tumbled, which made the deal less attractive to Zions.

In the end, investors representing just 33.7% of Zions shares voted to approve the acquisition, while 45.2% were opposed. The deal’s unraveling was particularly painful because Zions had already laid extensive groundwork for integrating its crosstown rival. Less than two weeks after the vote, Wells Fargo announced a deal to buy First Security.

As Simmons reflected on the failed acquisition, he was thoughtful and soft-spoken. “It was a very taxing period of time,” he said.

A key lesson that Simmons drew from the episode was that the bigger the merger, the more the acquirer has to sacrifice of its own culture. After shareholders rejected the deal, Simmons held a series of emotionally charged meetings with Zions employees.

He told them: “I can’t tell you that we’ll never engage in larger deals again, but what I can tell you is that never again while I’m working here will we ever call anything a merger of equals. There has to be a buyer; there has to be a seller.”

“Any employee who has ever seen Harris speak understands his authenticity,” she said. “He tells it like it is.”

The financial crisis that gripped the country in 2008 presented the next big challenge for Zions. The company, which operates in three Southwest states that were hit particularly hard by the mortgage meltdown, had a large concentration of commercial real estate loans, and many of them went delinquent.

In 2012, Zions repaid the $1.4 billion it received from the Troubled Asset Relief Program. But it was still holding a large portfolio of collateralized debt obligations whose value had fallen — a situation that led to Zions’ first big run-in with the post-crisis regulatory regime.

In December 2013, Zions announced that due to the portion of the Dodd-Frank Act known as the Volcker Rule, it would not be allowed to hold the CDOs to maturity. The company said that it would have to take a one-time, after-tax charge of $387 million as a result.

One month later, five federal agencies issued an interim final Volcker Rule that cushioned the blow to Zions, though the company still decided to sell off a portion its CDO portfolio in an effort to reduce its risk profile.

Simmons chafed at what he saw as the unfairness of post-crisis rules aimed primarily at big banks being applied to Zions, which was among the smallest companies designated as a systemically important financial institution. At the time, Zions Bancorp. had around $55 billion in assets, putting it not far above the $50 billion SIFI threshold.

“Sometimes we joke about ourselves as being an itty-bitty SIFI,” Simmons later told a congressional panel.

Rethinking a longtime strategy

Zions has long prided itself on being a collection of distinct banks sprinkled throughout the West. The company operates California Bank & Trust, Nevada State Bank and National Bank of Arizona, among other units.

An emphasis on local control has been intertwined with a heavy reliance on commercial lending. Personal relationships with bankers tend to matter to business owners, and commercial loans, including commercial real estate, account for about three-quarters of Zions’ total loans and leases.

For years, various Zions-owned banks operated under different charters. But by 2015, Zions had brought certain back-office functions under one roof, and Simmons was questioning whether the decentralized legal structure still made sense.

The central problem for Zions was that various units were reporting data in incompatible ways at a time when data consistency was becoming more important.

This industrywide shift was partly a result of post-crisis regulatory changes; banking agencies were placing greater emphasis on enterprise risk management, for example. And it was partly due to technology-driven business trends, such as the rise of digital marketing. In June 2015, Zions announced a plan to consolidate its seven charters into one.

Reflecting on his decision to

While the charter consolidation has led to greater efficiency, Zions retains its tradition of local authority. Executives across its 11-state footprint still operate under separate brands and still control pricing and most credit decisions, as long as they heed the company’s risk appetite.

“It’s still the local management teams and the connection to the community,” said Brian Klock, a banking analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. “Being able to keep the bank running every day, as if nothing has really changed, is big.”

Battling new regulations

Throughout his career, Simmons has been aggressive on the legislative and regulatory fronts. When he was elected chairman of the American Bankers Association in 2005, it galled some in the credit union industry. He had been a key player in getting Utah legislators to start taxing large state-chartered credit unions, an initiative that succeeded despite fierce grassroots lobbying by the other side. After the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act, his position as CEO of a midsize bank gave him the opportunity to be more persuasive in Washington than his peers at the crisis-tarnished megabanks were.

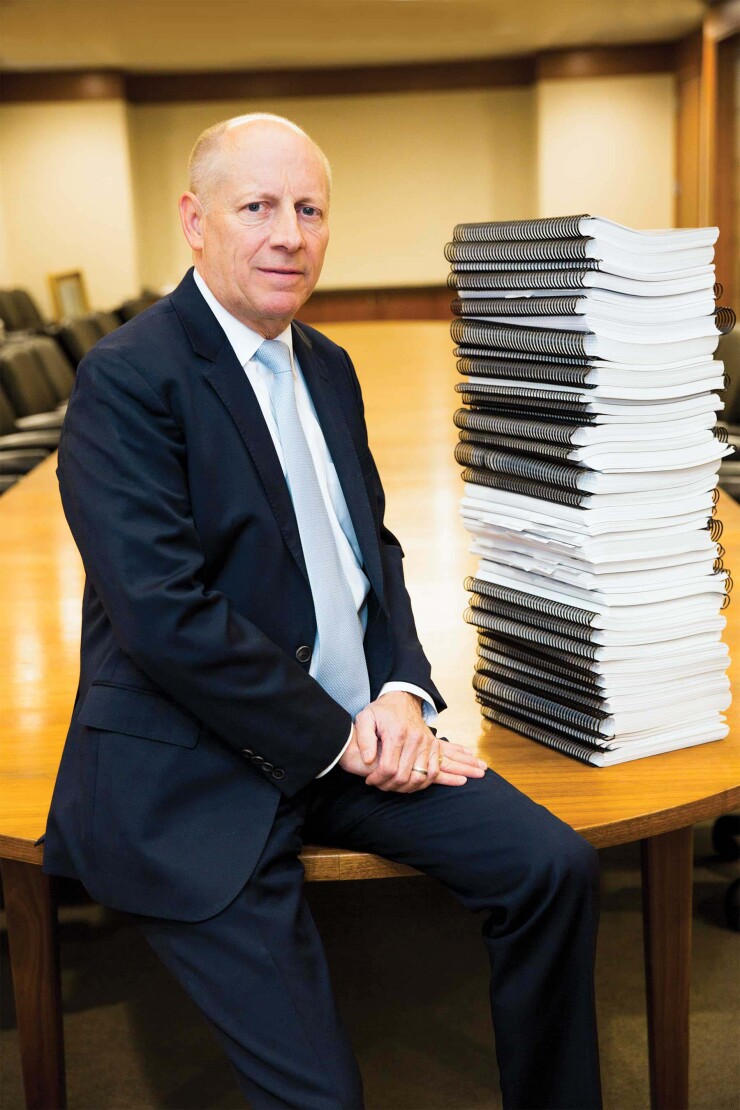

So it was no surprise that Simmons emerged as a key advocate for the regulatory relief law — signed by President Trump in May — that helps regional banks like Zions. On display in his office is a massive stack of paper — a single year’s stress test submission — that he showed to visiting lawmakers as a visual representation of the burdens imposed by the 2010 regulatory overhaul.

Simmons has been particularly galled by some stances of the Fed, whose stress test Zions failed in 2014. Though the central bank recently began promising more transparency, it has long kept its stress-testing models confidential in order to guard against banks’ efforts to game the results.

“Their approach to stress testing has been in my mind at best un-American and at worst illegal, with respect to the lack of transparency that it entails,” Simmons said.

He fought back on two separate tracks. First, he lobbied members of Congress to pass the regulatory relief measure, which raised the asset threshold for banks to be designated as systemically important. And second, he devised a plan that would help Zions even if the legislative effort failed.

The latter effort began back in 2015. Simmons figured that Zions ought to be able to escape its designation as systemically important if he could get rid of its holding company. He took the idea to a former senior regulator in Washington, who shot it down as unworkable.

But Simmons later got a different answer from Cohen of Sullivan & Cromwell, who noted that a provision in Dodd-Frank allows a systemically important financial institution to appeal its designation to the Financial Stability Oversight Council.

“It took about five seconds,” Cohen said, recounting his conversation with Simmons, “and he understood it.”

In September, the oversight council voted to end Zions’ status as systemically important. And on Oct. 1, the $66.7 billion-asset Zions announced that it had completed the merger of its holding company with its bank.

Zions’ maneuvers simplified its regulatory reporting. It is now a single entity that is regulated by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Fed is out of the picture — a result that could not have been achieved from the regulatory relief law alone.

“Basically this was an issue of the regulatory duplication,” Simmons said. “It’s not that the Fed was a difficult regulator. It’s just that everything was twice.”

A long-term perspective

Simmons, now 64, has been thinking a lot recently about the bank that he will eventually leave to his successor. And the question of whether Zions will be positioned to compete in the digital economy is at the heart of a large initiative to replace its core processing system.

“This project is an indication of Harris’ leadership style,” said Paul Burdiss, Zions’ chief financial officer. “Every decision he makes is for the long term.”

Sitting at his desk during the interview, Simmons noted certain similarities between the banking industry and the airline sector, both of which have layered additional technology on top of outdated computer systems over the decades.

Simmons once got stranded at the Denver airport because an airline’s ticketing system went down. When his flight finally began boarding, the gate agent resorted to writing down passengers’ names. Looking back at the episode, he shuddered at the thought that the same scenario could one day plague the banking industry.

Zions’ core conversion project, which was announced in 2013, is being overseen by Chief Information Officer

“We’re not replacing one system. We’re replacing multiple systems. And that’s what makes it so complex,” Smith said.

Zions’ new core system, which is being built with Tata Consultancy Services, a vendor based in India, is expected to offer a range of benefits. Those advantages include the ability to plug in services much more quickly and real-time payment functionality.

Smith described Simmons as a CEO who is steeped in the operational details of banking. “He needs to know how it all works,” she said.

The next phase

Zions Bancorp. has been led by a Simmons for the last 54 years, but the day will come when that is no longer the case.

“I don’t have any immediate plans to retire,” Harris Simmons said, “but time will bring that to pass at some point.”

He added that he is spending a lot of time on succession planning, focusing on a group of talented midcareer professionals who will eventually run the company.

Whoever does get tapped next will have big shoes to fill. Simmons has not only turned a Utah bank into a regional force — for the first six months of 2018, Zions reported a slightly higher return on equity than the industry average — he also has found many ways to give back to local communities.

Simmons serves as chairman of the board of regents of Utah’s higher education system. He is a longtime benefactor of the Utah Symphony. He has spent decades leading the efforts to fight homelessness in Salt Lake City. He also takes part in

When asked about his extensive work in the community, Simmons was characteristically modest, deflecting the attention to others. “This is, I think, part of the DNA of people who’ve been in this industry for a long time,” he said.

Scott Anderson, who is the president and CEO of Zions First National Bank and has worked with Simmons for 28 years, praised his boss’ community involvement, as well as his dedication to employees, customers and shareholders. Then he made a remark that surely would have made Roy Simmons proud.

“Harris is a banker to the core,” he said.