Live Oak Bancshares is set to expand an online lending program that management hopes will help the Wilmington, N.C., company compete more effectively against marketplace lenders.

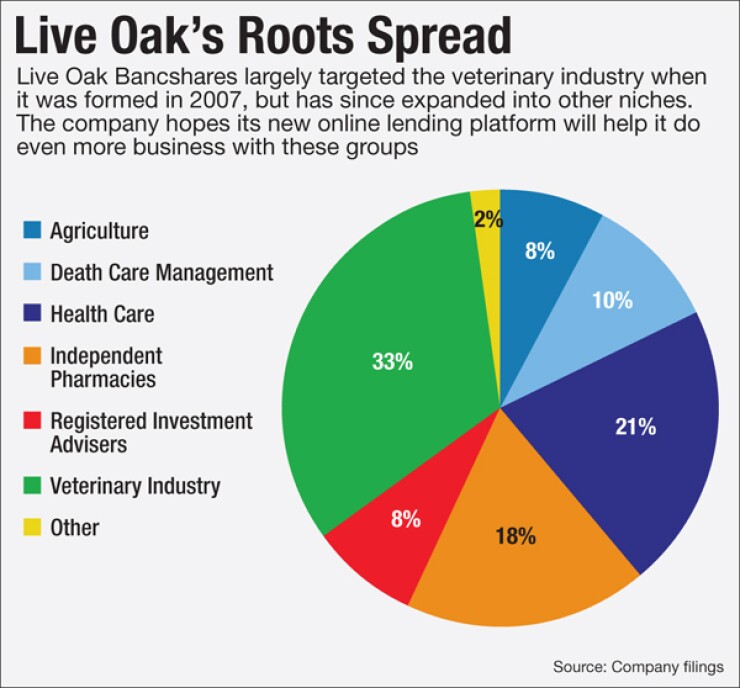

The $1.1 billion-asset company, which spent five months testing its digital platform, is ready to market services to borrowers within the 11 core industries that it serves. If the expanded rollout succeeds, Live Oak will consider offering its e-lending program on a national scale as early as next year.

The effort, which will provide loans ranging from $75,000 to $350,000, was largely influenced by inroads made in recent years by marketplace lenders.

-

For all the attention nonbank fintech firms get, they still have a long way to go before winning over key customer segments, such as business banking customers.

January 8 -

Live Oak Bancshares in Wilmington, N.C., one of the largest 7(a) program lenders in the U.S. last year, has promoted Greg Thompson to chief operating officer.

January 8 -

Live Oak Bancshares in Wilmington, N.C., has filed registration documents for an initial public offering, with plans to raise up to $86.3 million.

June 22

"The nonbank lenders out there demonstrated the massive market opportunity that exists," said Neil Underwood, Live Oak's president. Nonbanks "have also demonstrated that banks are not good at lending to the small-business market."

Live Oak, which began working on the project in mid-2014, originated $20 million in loans during a testing phase. The results surpassed targets in several areas.

"Going in, we figured our average loan size would be $100,000," Underwood said, noting that the actual average was double that amount. "That's good news to us. The click-to-close period has also exceeded our expectations. It takes about 10 days, and no credit decision has taken longer than 48 hours to make."

The time it takes to make a credit decision and fund loans is critical, since small-business borrowers have proved willing to pay a higher, "arguably crushing" rate for quickness and convenience, Underwood said.

Unlike most nonbank lenders, Live Oak's platform is not entirely automated. The company uses credit scoring technology to qualify applicants, though the ultimate lending decisions are made by bankers. Live Oak sought to streamline the lending process without compromising its underwriting standards, Jason Lumpkin, a senior loan officer and leader of the company's e-lending team, said.

"Borrowers have to be able to repay their debt from cash flow," Lumpkin added. "That remains fundamental."

The hybrid nature of Live Oak's platform, which pairs human decision-making and automated credit scoring, comes at a cost. Live Oak's staffing nearly doubled last year, to 337 employees, and salary expense rose by 73% in the fourth quarter from a year earlier, to $12.7 million. Still, Live Oak is committed to assigning each borrower who qualifies for a loan to a "dedicated banker" who will manage the application.

"We're trying to treat every customer like they're the only customer of the bank, and we mean that," Underwood said. "Speed can be a competitive weapon, but what if you could have both speed and customer service? That's what we've been working on the past two years."

The volume of loans Live Oak originated during e-lending's testing phase is an encouraging figure, said Aaron James Deer, an analyst at Sandler O'Neill. "They've used this period to fine-tune, to make sure it's hitting their objectives and make sure the customer experience is" a positive one.

Deer said he is projecting 18% growth for Live Oak's origination volume this year. The e-lending initiative is factored into that figure, though Deer said the buzz surrounding the effort is exciting. Live Oak "is doing something different," he said.

"They're not pure fintech," Deer added. "They're a bank, but they're using technology in a more constructive way than we've seen with any other bank."

Live Oak has been willing to experiment with technology since its founders, including Chairman and Chief Executive Chip Mahan, founded the company with the expectation that branches would become obsolete eventually.

That attitude sets Live Oak apart from most other bank, said Ron Shevlin, director of research at Cornerstone Advisors in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Banks have become adept at using digital channels, such as mobile banking, to serve their existing customers, but few are using them to acquire new business like Live Oak is doing, Shevlin said. A recent survey by Cornerstone found that banks haven't fully realized the importance of using digital channels as growth engines.

"I don't think [bank CEOs] understand how to use digital channels as a means to attract business," Shevlin said. "Most CEOs came up in commercial lending. All they understand are relationships and people. For them, it's all about getting bodies on the street and driving growth – guys who can meet with borrowers and close loans."

Shevlin said many banks are not ready to go as far as Live Oak has in rolling out a turnkey lending platform, though he said they should give much more thought to ways they can use digital channels in attracting customers. "I don't think bankers recognize what small-business customers' behavior is when it comes to shopping and research," he said.

"When I look at bank websites, they don't go in-depth in terms of the information they provide," Shevlin added. "They pretty much tell people, 'We've got loans.' Everyone knows banks make loans. Their question is, 'Are you the right bank for me?' "

In its first seven years, Live Oak has established itself as one of the nation's premier Small Business Administration lenders. The company, which earned $20.6 million last year, derives the lion's share of its revenue from loan sales, which totaled $641 million in 2015.

With its e-lending platform up and running, Live Oak's next major challenge is to move into non-SBA conventional lending. "We'd like to evolve into a digital small-business bank," Underwood said.