-

These deals are hard to put together but are well worth it -- if management teams can get through the problems of working together. Sterne Agee's Michael Barry and Daryle DiLascia explain.

February 14 -

The pairing of Rockville Financial in Connecticut and United Financial in Massachusetts would create a $5 billion-asset bank that can get more efficient yet invest in growth. More deals like it have been happening around the country this year.

November 15 -

Wilbur Ross says in an email to American Banker that BankUnited tried to sell only after an unnamed investment bank told management it could fetch a "substantial premium above market."

January 24 -

Did an anonymous open letter to BankUnited CEO John Kanas, emailed to all of the bank's employees, imploring him not to sell the bank really have an impact on the decision to abandon the sale?

January 19 -

Chief John A. Kanas has hired Goldman Sachs Inc. to help it find a buyer, according to news reports. Reasons for selling a bank that has outlined big growth plans puzzles observers.

January 13

An architect of one of the signature bank M&A deals of 2013 summed it up as merely a conversation between two guys.

"It was just Dick Collins and me," says Bill Crawford, the chief executive of Rockville Financial (RCKB) in Connecticut. Collins is the chief executive of United Financial Bancorp (UBNK) in West Springfield, Mass., which

Other executives, directors and advisors ultimately were involved, but Crawford's just-us-two comment highlights the personal connection that served as the deal's foundation. Private talks and mutual interest made it happen, not fishing for bids around the region.

Collins and Crawford's approach is bank M&A's predominant MO these days. Where auctions once ruled, banks are now opting to negotiate with one or maybe just a few partners in determining their future. Buyers are trying to learn from the mistakes of the past, sellers are viewing deals as partnerships, and they are all trying to figure out the best way to get ahead amid heightened regulation and smaller revenue.

Meanwhile, investors are more sensitive to stock dilution to their hard-earned tangible book values and regulators are taking a more studied approach to approving deals. The result? Bank deals have to make sense and be airtight more than ever.

"If you think about 2005 and 2006, valuations were strong, there were lots of buyers, regulators were approving deals quickly, [and] investors were tolerant of dilution," says Rick Maples, co-head of investment banking at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. "Now, there are fewer buyers, regulators are not giving away golden tickets, and investors are demanding a focus on structure. It all culminates with a discipline today that didn't exist five years ago."

Auctions were prevalent immediately following the 2008 economic collapse. Those postcrisis deals, however, were largely for the distressed banks that went to the highest bidders.

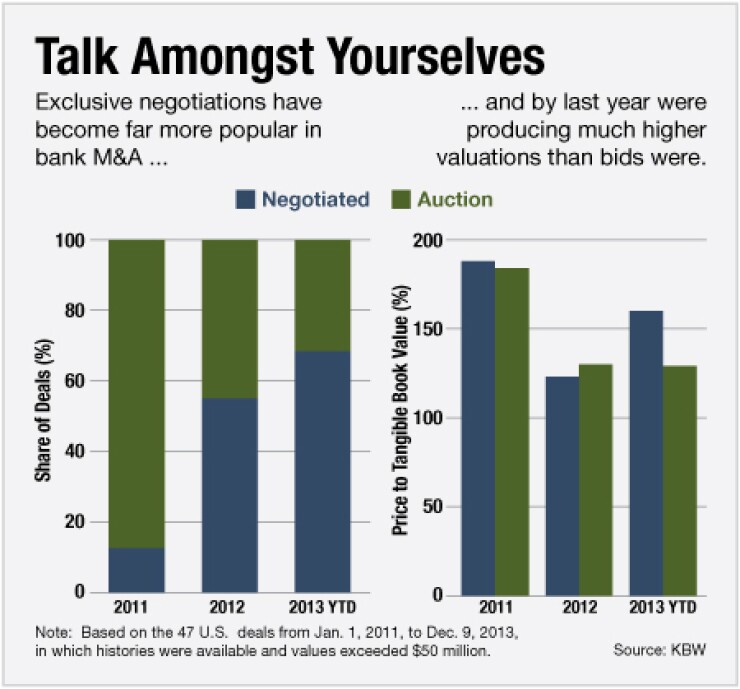

Since then credit quality has improved, and negotiated deals have been on the rise, according to a KBW study last year. It focused on 47 deals in recent years that were valued at $50 million in which either it acted as a bank advisor, or for which price and other transactional information were publicly available. The study defined scenarios with more than five suitors as an auction.

Negotiated transactions made up 12.5% of such deals in 2011, KBW said. By December 2013, that percentage had jumped to nearly 70%.

Robust auctions are rare now, says Bill Hickey, the co-head of investment banking at Sandler O'Neill.

"It is very company specific, but it is an aberration in today's market when a bank can go out and have more than five banks ready to be a buyer," Hickey says.

Clients are driving the change, not their advisors, investment bankers say. The effort involved in organizing an auction is said to be on par with the work involved in helping buyers and sellers determine a fair exchange of shares. Essentially, each process pays about the same.

Fresh memories of the downturn and intense regulation are prompting even the most enthusiastic buyers to cautiously approach M&A.

"Mergers were one of the places where banks got themselves in trouble, so I think they are trying to make smarter choices," says Ted Peters, the chief executive of the $2 billion-asset Bryn Mawr Bank (BMTC) in Pennsylvania.

Due diligence in auctions used to involve a 50-page confidential packet with the opportunity to do a final "confirmatory" follow-up, Maples says.

"Now, it is access to a data room that has 10,000 pages of data," he says. "That lends itself to a negotiated transaction."

Part of the due diligence is hunting for land mines, and part of it is ensuring that the deal is really going to make the bank more profitable.

Scale has long been an industry buzzword and a goal of M&A, but it has taken on a new meaning in the current environment. Before, scale was really a synonym for being in multiple markets; the biggest banks sought coast-to-coast operations. Now, scale is defined by taking a large share in business segments or geographic markets where banks already operate, and doing it all more efficiently.

"Banks are trying to get scale, but that was true five years ago, too," Maples says. "But in the past it was size scale, now they are looking for business scale."

The simple answer as to why there are more negotiated transactions could be boiled down to a lack of buyers.

"We might go out and contact nine potential parties, three are interested and maybe two bid. Or maybe no one bids," Maples says. "That is happening way more often than it used to. So, as a seller, you might be more open to a negotiated deal."

There are various reasons why the pool of possible buyers is shallow. Some were burned by the downturn and have no interest, at least for now, in returning to M&A. Others are constrained by lingering regulatory issues. Some could just be overwhelmed with options if regulators are only giving them a few bites per year at the M&A apple, they want to choose wisely.

Other buyers just don't like auctions and are using the lack of other buyers in the market to their advantage.

Peters at Bryn Mawr is an example of a banker who doesn't like to participate in auctions. He says his style of M&A lends itself to negotiated transactions. Bryn Mawr's deals are often marked by a lot of work put into making sure key employees stay, for instance.

"We want to put together companies in a thoughtful manner so that it works well," Peters says. "Some banks prefer to go in like Attila the Hun. That's not us."

Bill Crawford, the chief executive of the $2.5 billion-asset Rockville Financial, says he finds auctions "sterile," and prefers the connection created when two bankers are hashing out the details of how to make a potential deal between them work.

"I would have very little interest in a company being auctioned. A lot of work goes into determining the value, and the auction process doesn't allow for it as much," Crawford said in an interview last month. "The only way I'd do it is if it was clear that I had nothing but cost saves."

Additionally, given shareholders' sensitivity to tangible book value dilution, Crawford says he would fear being accused of paying too much.

"Your investors are going to say, 'Great, you won. That means you overpaid,' " he says.

Savvy acquirers are always on the prowl, investment bankers say, and their targets are well aware of their interest. If a buyer can catch a seller before it even contemplates auctioning itself, the buyer has time to make a strong case for how much their combined stock would be worth.

"The best buyers are always out there talking to their potential targets in a non-threatening way, saying, 'If you're ever going to do something, give us a call,'" Hickey says.

As the industry works to repair its tarnished image, there is a heightened desire among directors of potential sellers to keep merger talks confidential, says Rick Maroney, a managing director and principal at Austin Associates, an investment bank based in Toledo, Ohio.

"I know a lot of boards that don't want to get into auctions because of the ability to keep it under wraps," Maroney says. "They'd prefer to work with a preferred buyer."

Given the possibility the auction might not pan out likely adds to the desire to keep it quiet.

In 2012 it leaked that BankUnited (BKU), a $15 billion-asset bank in Miami Lakes, Fla., had initiated a potential auction. Its employees penned open letters to the company asking it not to sell. Ultimately,

Maples says the KBW examination showed that before 2008, sellers had multiple bidders 70% of the time. In the last few years, 65% of the deals have seen one final bidder.

"That is a tremendous shift in the odds," Maples says.

Of course, even in negotiated transactions sellers still want to know they got the best deal. To that end, experts say buyers allow prospective sellers to do a controlled market check, essentially allowing the sellers to approach a couple of others just to gauge interest.

"There are auctions and then there are auctions," says C.K. Lee, a managing director at Commerce Street Capital, a Dallas investment bank. Although traditional auctions with several bidders are falling out of favor, "we still present sellers coming to market with what we think are the four or five best positioned companies to do a deal."

Prolific bank buyer Prosperity Bancshares (PB) in Houston allowed FVNB in Victoria, Texas, to

Dealmakers say there could also be an increase in go-shop provisions in definitive agreements, which basically allows the seller to consider other deals after an agreement is struck.

Banner Corp. (BANR) gave Home Federal (HOME) such a provision in its agreement and in October, Home announced that Cascade Bancorp (CACB)

Some are also selling begrudgingly. Conventional wisdom would then say that those banks should try to sell to the highest bidder. But the highest prices paid in auctions today are likely a far cry from what the sellers think their bank is worth. In that case, sellers would rather take the stock of a partner they pick and hope for some upside potential, Maroney says.

"They don't really want to sell, but feel compelled to given all the challenges in regulation and revenue generation," Maroney says. "They get some value, but increased liquidity and an organization with more products and services. They don't feel like they are selling out."