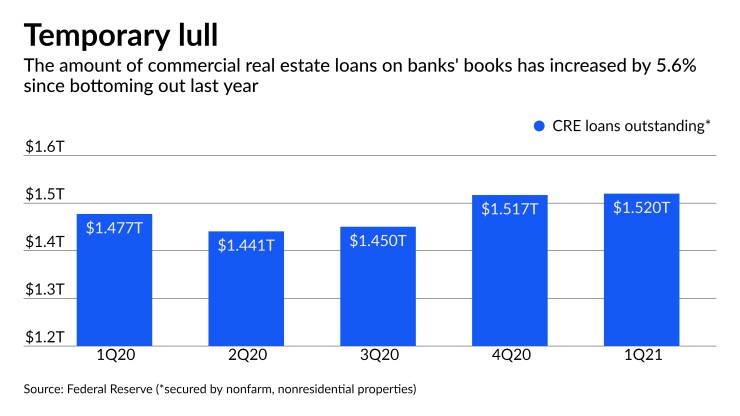

Demand for small business and commercial real estate loans is picking up, creating some optimism among lenders and more temptation to loosen standards to land those borrowers.

Given an undercurrent of uncertainty still tied to the pandemic, the shift may present a layer of risk should the economic recovery fail to live up to

Banks also expect to face competition from credit unions, fintechs and other nonbanks for new business.

Bankers, particularly those at community banks, discussed “improving pipelines” during recent first-quarter earnings calls, said David Long, an analyst at Raymond James. “We expect demand for credit will pick up and cause an acceleration in loan growth in the back half of the year.”

The Federal Reserve’s quarterly survey of senior loan officers found that, while loan growth was tepid in the first quarter, excluding the impact of

The survey found that banks generally loosened standards for borrowers of all sizes for the first time since the pandemic began.

For some bankers, loosening means returning to pre-pandemic standards.

“We’ve relaxed some standards along with a much-improved outlook for borrowers,” said Shan Hanes, president and CEO of Heartland Tri-State Bank in Elkhart, Kansas. “That said, we had tightened standards in 2020, and what we’ve done is really start to loosen things back close to normal.”

Commercial real estate loans, for instance, may now qualify for smaller payments compared to a year ago, Hanes said.

The $133 million-asset Tri-State is a prominent

Every small business in Tri-State’s loan book survived the fallout from the pandemic and the bank has already financed five new businesses that have recently opened.

“A year ago, I don’t know if I would’ve bet on anything like the solid recovery we’re seeing, but things are looking quite good coming out of this,” Hanes said.

Despite an upbeat assessment, Eric Corrigan, head of the financial institutions group of Commerce Street Capital, said setting pricing and terms for loans has to be done cautiously.

“There’s still a lot of uncertainty around things like offices and retail,” Corrigan said.

“With underwriting, do you base expectations on what normal looked like in 2019 or what it could look like in 2022?” Corrigan added. “These things present unique challenges and risk. Diligence is going to have to go a lot deeper for a lot of CRE and commercial credits, and that may have an impact on growth.”

An uninterrupted economic recovery, while looking likely, is hardly a sure thing, with industry observers pointing to the Labor Department’s latest jobs report.

Employers added 266,000 jobs in April, a number that was well below the one million jobs economists polled by Dow Jones had, on average expected. The unemployment rate rose to 6.1% from 6% a month earlier.

“Talk about a turd in the punchbowl,” Corrigan said.

Some employers are struggling to fill entry-level jobs, Corrigan said, but others may have scaled back because of

“Clearly there’s great optimism for the balance of the year,” Corrigan said. “I share in that, but I just think it could be bumpy.”

For a fifth straight month, Creighton University’s monthly survey of bank CEOs in the Midwest and south-central United States found executives confident in the year ahead, in terms of the outlooks for their banks and the economic vibrancy of their markets.

But bankers who participated in the survey said that, while farmland and home prices are strong and climbing, reflecting confidence, there are potential warning signs of inflation and unchecked exuberance that could soon create worry.

Reminiscent of the

The economic advances have largely been driven by federal stimulus programs, including checks delivered to most households and extended unemployment benefits, said Ernie Goss, the economist who spearheads the Creighton survey. Low interest rates have also played a big role.

The recovery is likely to prove uneven in the second half of the year, said Brad Milsaps, an analyst at Piper Sandler. He said markets with high vaccination rates and economies that have fully reopened, such as Phoenix and Austin, Texas, could excel on their own.

Others may have a more difficult climbing back as government assistance wanes, including cities such as New York, Chicago and San Francisco that are dependent on expensive downtown office towers to attract workers on a daily basis.

With more remote working, even after the pandemic ends, fewer people are likely to commute to work — or pay more to live close to work — and real estate at the cores of major cities could take much longer to bounce back as a result.

“Overall, I’m confident in the recovery and the outlook for banks, but some parts of the country will inevitably be playing catch-up to others,” Milsaps said.