Startups that provide early access to workers’ earned wages are jostling over key aspects of pending California legislation that would create the nation’s first-ever regulatory framework for the nascent industry.

The state Senate passed a bill 35-0 last month, but interviews with executives in the fast-growing sector revealed big disagreements about the legislation. Those disputes reflect key differences in their firms’ business models.

The proposed rules stand to help the companies, broadly speaking, by making clear that their products are not loans. The firms charge fees for access to income that workers have already earned, but have not yet received due to time lags in the payroll cycle.

Many of the companies partner with employers, which offer the products as an employee benefit. But because it is not clear today whether financial regulators view these companies as lenders, their business models can sometimes be a tough sell in corporate America. The pending legislation would solve that problem in the nation’s largest state.

“In the lack of regulation, there’s just a lot of uncertainty and concern,” said Frank Dombroski, the CEO of FlexWage Solutions.

Earned wage providers offer a new option for U.S. workers who lack a large enough financial buffer to cover irregular expenses. In a 2017 survey by the Federal Reserve, four in 10 U.S. adults said they would be unable to cover a $400 expense without borrowing or selling something.

Fees in the industry can vary substantially, depending on the provider and how often the consumer uses the product, but there is general agreement that these companies offer a better option than both payday loans and overdraft fees.

A paper last year by researchers at the Harvard Kennedy School

As the California Assembly prepares to hold hearings on the legislation, some of the companies that would be affected are seeking to loosen its consumer-protection provisions, arguing that the proposed rules would limit the number of cash-starved workers they can serve. Consumer advocates are trying to push the legislation in the opposite direction.

There are also diverging views about the bill’s treatment of certain companies that bypass employers and offer funds directly to consumers, which would be brought under the same regulatory umbrella as the firms that partner with employers. Meanwhile, at least one early access provider is taking umbrage at what it sees as the outsize influence of San Jose, Calif.-based PayActiv, which has led the push for legislation.

Industry officials are pressuring lawmakers in Sacramento to pass a bill this year. If legislation is passed, analysts say that the state's framework is likely to be adopted elsewhere.

“You would think that if California passes a bill like this, it could serve as a model for other states,” said Leslie Parrish, a senior analyst at Aite Group.

In an April report, Parrish estimated that U.S. employees accessed their wages early 18.6 million times last year. Workers received an estimated total of $3.15 billion, which works out to an average of nearly $170 per withdrawal.

“This emerging market is poised for exponential growth,” the report stated, “as solution providers increasingly partner with large employers as well as benefit and human resources platforms.”

The legislative push in California began after the Department of Business Oversight, which regulates financial institutions, made inquiries last year of companies that offer early access to earned wages, according to two sources familiar with the situation.

Democratic Sen. Anna Caballero introduced the legislation, but PayActiv is listed as its sponsor. Unlike in many other states, bills in California can be sponsored by corporations, unions and other interest groups.

The legislation includes provisions that appear likely to offer PayActiv a leg up over some of its competitors.

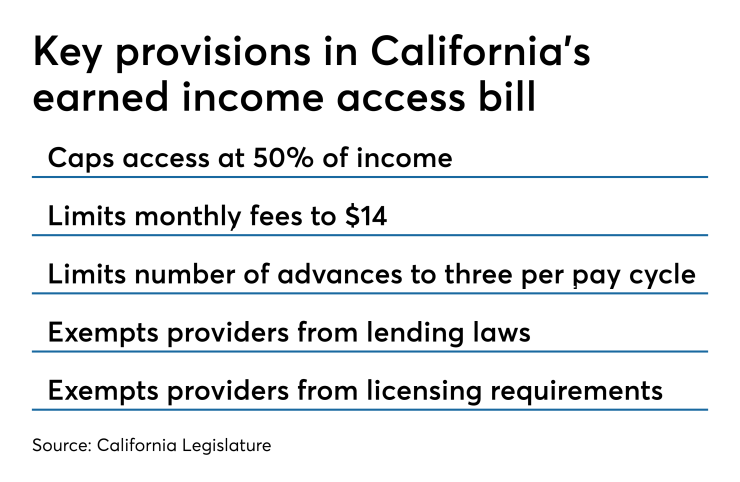

For instance, the bill would establish a $14 limit on the monthly fees that can be charged, and it would prohibit providers from delivering funds more than three separate times during each pay period. It would also bar consumers from withdrawing more than 50% of their unpaid income.

PayActiv charges users a flat fee of $5 for pay periods that are two weeks or longer, and a flat fee of $3 for weekly pay periods, according to an analysis prepared by the California Senate Judiciary Committee.

The company caps the amount of unpaid income that a consumer can withdraw at 50%, though a source familiar with the situation said that PayActiv uses a different method for calculating pay than the legislation contemplates.

One of PayActiv’s competitors is New York-based DailyPay.

DailyPay allows workers to access their earned but unpaid wages on a daily basis and does not cap the amount that they can tap.

DailyPay said in comments to the California Legislature that the bill is drafted in a manner to protect one company’s business model. The company pointed to the 50% limit on accessing earned income and the $14 per month fee cap, among other examples.

A source familiar with DailyPay’s arguments said that the proposed pricing rules could limit the ability of early wage providers to work with smaller, less credit-worthy employers, since those firms are more likely than big corporations to go out of business and evade their payroll obligations.

In its analysis of the bill, the Senate Judiciary Committee stated: “The criticism that these limitations mirror the business model of PayActiv, the sponsor of the bill, are not unfounded.”

PayActiv Chief Operating Officer Ijaz Anwar said in an interview that his company is not controlling the legislative process.

“We did initiate the process,” he said. “But once that was done, it has been a collaborative effort.”

The current version of the legislation is also facing criticism from consumer advocacy groups, which want stricter limits on fees and usage. In an April letter, the Center for Responsible Lending, the National Consumer Law Center and the Western Center on Law and Poverty warned of the risk that unscrupulous actors will exploit certain provisions.

Consumer groups argue that early access to wages can result in 'a hole in the next paycheck, which can create future problems and a dependency on chronic use.'

The groups argued that exemptions from California’s credit laws should be limited to products that charge no more than $5 per month. They also asked that access to early wages be limited to six times per year. Under the bill, a worker could spend up to $168 annually on fees.

“While early income access can help a worker cover an unexpected expense that the worker cannot handle out of the last paycheck,” the consumer groups wrote, “the result is a hole in the next paycheck, which can create future problems and a dependency on chronic use of early wage access.”

The consumer groups also want language added to the bill to require earned income access providers to be licensed by the Department of Business Oversight, which would not have supervision and enforcement authority under the current version.

Department spokesman Mark Leyes declined to comment on the legislation.

Some industry officials argued that, contrary to the views of consumer groups, the bill’s limits on fees and usage are too strict.

ZayZoon President Tate Hackert said that his company currently allows users to access 50% of their earned wages, but he wants to raise that limit.

“I think lower-income individuals can be hurt by that,” Hackert said, arguing that the legislation should allow workers to access 70% to 80% of their earned but unpaid wages.

Another big sticking point in Sacramento involves the status of companies that offer early access to unpaid wages, but do so through direct relationships with consumers, rather than by connecting into employers’ payroll systems.

Because the employers are not directly involved in these transactions, the advances must be repaid by the consumer, instead of being deducted from the employee’s next paycheck.

Consequently, the providers must get in line along with other billers at the end of the pay cycle, and they face a significantly higher risk of loss than the companies that partner with employers.

Firms that use the direct-to-consumer model include Earnin, which allows its users to cash out up to $100 per day, and Dave, which offers advances of $5 to $75.

Under the California bill, these companies would be treated the same way as firms that partner with employers. Neither business model would be classified as providing credit to the consumer.

In an interview, Dave CEO Jason Wilk expressed support for the legislation.

“I would say it’s still a work in progress, as far as we know. But overall we are a fan of regulation in this space,” Wilk said. “To the extent that we can get regulation in a major state like California, it’s helpful.”

But consumer advocates and at least some of the firms that work with employers argue that direct-to-consumer companies should not be exempted from lending laws. They contend that if the consumer has an obligation to repay the advance, the transaction should be treated as a loan.

American Banker

In an interview Wednesday, Jon Schlossberg, the CEO of Even, which partners with employers such as Walmart to provide early access to their workers’ earned wages, sounded surprised to learn that the California legislation lumps together both business models.

He said that companies that advance money directly to consumers can put their customers on a treadmill that is similar to the debt cycle that works to the advantage of payday lenders.

“That is in fact the most dangerous kind of earned wage access,” he said.

The California Assembly’s banking committee has scheduled a July 8 hearing on the legislation.