Many banks redesigned branches and ATMs to accommodate customers with disabilities. Now the accessibility initiative is moving to a new front: addressing the unique financial barriers facing this community.

People with disabilities already face limited employment prospects, and those who receive certain disability benefits cannot accumulate more than $2,000 in assets without risking the loss of their benefits. That has the unintended consequence of discouraging people with disabilities from pursuing employment or even saving for a rainy day.

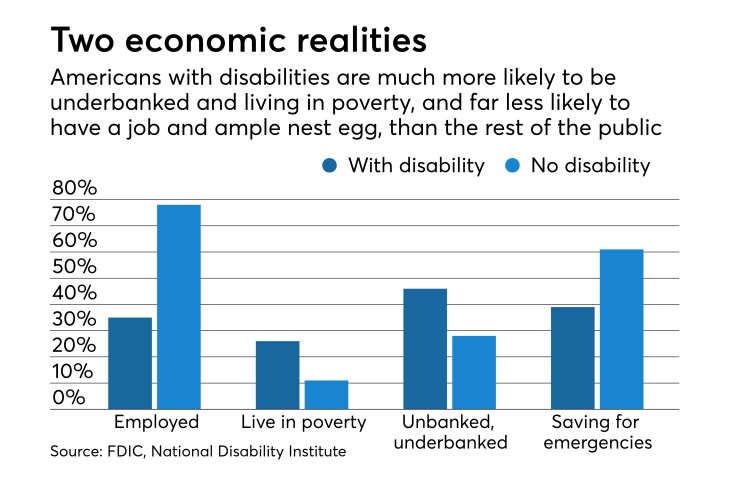

As a result, Americans with disabilities are much more likely to be unemployed, poor and unbanked or underbanked, and they are far less likely to have saved for unexpected expenses.

A relatively new type of investment account now allows those who receive disability benefits to save for some of the added expenses of having a disability — transportation needs or assistive technology, for example — but just a fraction of those who could open one of these accounts have done so. Proponents say that more specialized financial literacy programs are needed not only to raise awareness of those accounts, but more broadly to bring people with disabilities into the banking system.

A new initiative between the National Disability Institute and a financial inclusion arm of Citigroup intends to do just that. The goal of the Empowered Cities project is to create specialized financial literacy training materials that can be used by any nonprofit, municipal government or financial institution that regularly interacts with people with disabilities.

Michael Morris, executive director of the institute, said that traditional financial literacy programs often ignore the distinct financial challenges encountered by people with disabilities. His group wants to change that by reaching those who have regular contact with people with disabilities, so that they know how to tailor financial literacy programs to the needs of those consumers.

“Integrating traditional financial counseling with the intricacies and complexities of eligibility for benefits and how to work the two together is a big part of what we do,” Morris said.

The program kicked off in January with a New York pilot called EmpoweredNYC. The institute will work with the Office of Financial Empowerment in New York City’s Consumer Affairs Department, as well as the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities. For now, their efforts are focused on testing financial coaching strategies for city employees and staff at disability services agencies throughout the city.

Citi Community Development, which leads financial inclusion efforts for Citigroup, kicked in $2 million, half of which will go to the New York effort. The coalition hopes to fine-tune its tools and techniques there before rolling them out to other major cities, like San Francisco, Chicago or Miami.

“Everybody has complex financial lives for one reason or another,” said Bob Annibale, global director at Citi Community Development. For people with disabilities, that might mean navigating a maze of benefits, insurance and unemployment, but there’s been a dearth of specialized financial training for people who might counsel those with disabilities, he said.

Morris and others say that is because of long-held misperceptions that people with disabilities lack much money and therefore have no need for financial advice. Yet American workplaces are evolving and assistive technology are expanding job possibilities.

“Historically, people with disabilities have really been neglected with regard to being provided with financial literacy skills,” said Chris Rodriguez, director of the National ABLE Resource Center. “Now we’re in a much better place where people with disabilities can pursue employment, where they can have these tax-advantaged savings accounts, and we need to do a better job in providing people with disabilities the financial literacy tools and the assistance they need to feel comfortable in the banking space.”

The Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) Act, passed in 2014, allowed states to set up state-administered accounts modeled after 529 college savings plans. Rodriguez said that at least 30 states have initiated or set up such programs, and he expects more to follow suit.

The details vary by state, but the accounts usually allow a person to save up to $300,000 or more without endangering their disability benefits. They are administered and managed by the state’s treasurer and typically held at investment funds like BlackRock or Vanguard.

However, the $142 billion-asset Fifth Third Bank in Cincinnati also offers an ABLE account in 17 states and provides a debit card so the account can be used on a more transactional basis, say for medical expenses.

The enrollment figures are still relatively small, though. About 16,000 people have opened ABLE accounts nationwide, even though as many as 8 million to 10 million are eligible nationwide, Rodriguez said. A spokesperson for Fifth Third said the bank currently has 1,500 ABLE accounts with deposits totaling about $4.1 million and averaging $2,700 per account.

ABLE accounts are still a fairly new product — the first ABLE program was started in 2016. So, on one hand, it unsurprising that they have been underutilized so far. Also, most banks do not offer ABLE accounts as the financial institution for any given program is usually selected by a state’s treasurer.

Of course, banks must ensure their branches, ATMs are accessible under the Americans with Disabilities Act, but there are plenty of other ways that banks can show their support for the disability community.

Regions Financial in Birmingham, Ala., regularly collaborates with local disability groups to find out what it can do better. That collaboration led to

Like many other banks, Regions has also made a better effort to hire people with disabilities. Morris said that is one especially promising trend he’s noticed in recent years, and he said it sends a powerful message to others with disabilities.

“Many people with disabilities will say that the most positive thing for them is to go into a neighborhood branch and talk to a person with a disability,” he said. “That makes them feel empowered.”