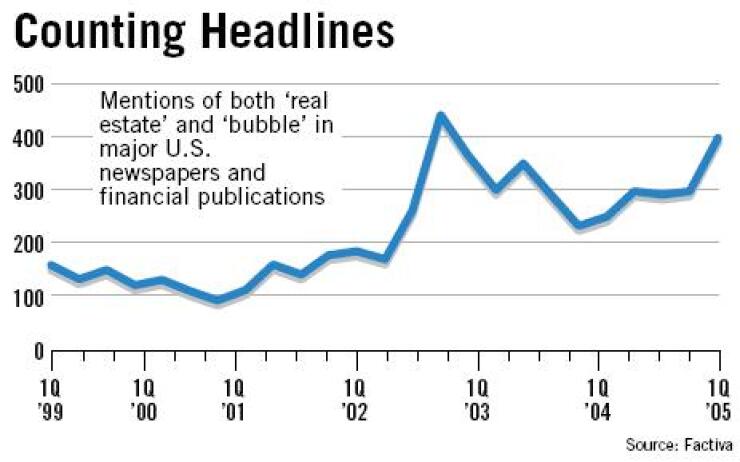

The uptick in mass-media chatter about real estate bubbles differs from previous ones in at least one way: This time some of banking's most sober commentators are contributing by subtly changing how they talk about housing.

Alan Greenspan may have kicked the mainstream coverage up a notch when he incrementally shifted his own position in March, but others at the Fed - as well as at the FDIC, the OCC, and Fannie Mae - have also voiced unease about the continued run-up in home prices.

Meanwhile, many industry professionals seem to agree - a first-quarter survey of 122 commercial lenders found that nearly half believe there is a property bubble.

None of this necessarily means that this time it's for real. For one thing, coverage in the general media is a notoriously unreliable barometer of economic trends. And those in the banking establishment who have changed their tone have not raised alarms about an imminent national correction; all have been quick to point out mitigating factors, such as the regional nature of housing markets and the fact that booms do not always end in busts.

Nonetheless, the change in emphasis among regulators and others is noteworthy.

For years Mr. Greenspan denied that a national bubble was something to worry about. In a speech last month, he essentially reiterated - word for word, at many points - his thoughts on the housing market from a speech he made in May, but he added a telling note of caution.

The crux of both of his speeches was that, despite analyst concerns, "a destabilizing contraction in nationwide house prices does not seem the most probable outcome" of the recent run-up.

But in last month's speech, Mr. Greenspan also said, "The recent marked increase in the investor share of home purchases suggests rising speculation in homes."

As if to reassure listeners, he followed by saying, "Even should more-than-average price weakness occur [nationally], the increase in home equity as a consequence of the recent sharp rise in prices should buffer the vast majority of homeowners."

Those anxious about a bubble pointed to investor purchases as a red flag much of last year. Fannie Mae, which until then rarely raised concerns about the housing market, joined the chorus in October, when its then-chief executive, Franklin Raines, spoke at a mortgage industry convention in San Francisco.

"I've spent a lot of time over the last few years arguing that there is no 'housing bubble,' and nationally that's still true, but we are seeing investor-driven price increases in certain markets," including northern California, he said. "These markets could soften as investor demand wanes, as it inevitably does."

(Mr. Raines was forced out over accounting issues two months later.)

In its February "FYI" electronic bulletin, the FDIC said, "The lion's share of [regional] home price booms have not ended in busts historically" - only stagnation.

But its conclusion was far from sanguine. "Although this paper demonstrates that relatively few metro area housing booms have ended in busts, there are reasons to think that history might be an imperfect guide to the present situation," the FDIC said.

"Foremost among these are changes in credit markets that are pushing homeowners - and housing markets - into uncharted territory," the bulletin said. Those changes include explosive growth in subprime loans and borrowers who are more leveraged.

Richard Brown, the FDIC's chief economist, acknowledged that the "level of concern is a little bit higher with the acceleration of home prices" in mid-2004 - one reason for the study.

"I think if we had talked a year ago we would have said, 'Yeah, prices have risen faster than fundamentals, but not that much faster,' " Mr. Brown said in an interview.

He stressed that a sharp run-up is not necessarily followed by a bust and that economic shocks usually play a vital role in a bust. Only 17% of the booms the FDIC identified in the two decades before 1998 turned into a five-year period in which nominal prices fell 15%. (The paper defined a boom as a 30% rise in inflation-adjusted prices in three years.)

The paper also said there were 33 boom markets in 2003 - the highest yearly total for the 25 years the agency studied, and 50% more than in 1988.

"I would hope lenders and borrowers in all these markets … take the long view," Mr. Brown said.

In a speech last month, Acting Comptroller of the Currency Julie Williams raised price declines as part of her warning about the growing credit risks stemming from aggressive retail lending.

The willingness of lenders to offer, and of borrowers to take, increasingly popular interest-only mortgages, for instance, is often "predicated on continued healthy price appreciation for residential properties," Ms. Williams said.

"If housing prices should stabilize or even begin to fall, and borrowers see their equity dwindle - or, worse yet, the value of their home fall below what they owe - there's no telling how these loans would perform," she said.

(In April of last year, former Comptroller John D. Hawke Jr. said in congressional testimony that the OCC was watching developments in areas of credit quality that remained "vulnerable," including "certain real estate markets and property types." In a December speech, Ms. Williams said the OCC was concerned that banks were not properly recognizing and adjusting for "weakness in certain real estate markets and property types.")

As late as mid-2004 Fed officials were generally quick to dismiss data on diverging prices and fundamentals as untrustworthy. But Mr. Greenspan is not the only one at the Fed taking another look.

According to the minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee's December meeting, "some participants" fretted that "the prolonged period of policy accommodation had generated a significant degree of liquidity that might be contributing to signs of potentially excessive risk-taking."

One of those signs was "anecdotal reports that speculative demands were becoming apparent in the markets for single-family homes and condominiums."

In January, Fed Vice Chairman Roger W. Ferguson Jr. made a speech to the Real Estate Roundtable, a Washington trade group, on the interplay between bubbles and recessions. He did not mention any particular bubble to the group of chief executives from real estate, finance, and investment companies.

"Unfortunately, detection of a bubble, which is problematic even ex-post, is an even more formidable task and arguably becomes virtually impossible in real time," Mr. Ferguson said. For this reason, "a clear-cut policy response to suspected waves of exuberance cannot be suggested."

Still, he said, it is a good idea to have a healthy financial sector and strong and prudent regulation of it during the boom, and to pursue "fiscal prudence and price stability" before a bust, so that action can be taken swiftly when it hits.

Recessions caused by asset-price bubbles are not necessarily worse than others, Mr. Ferguson said - perhaps a window into any effect on the Fed's rate decisions.

Scott Albinson, a managing director at the Office of Thrift Supervision, said it is keeping a closer eye on the possibilities on a "case-by-case basis" as rates rise but sees little evidence of a "huge, nationwide bubble." (One recent concern is that some homes apparently are being purchased before construction with an eye toward quick sales, he said.)

"It certainly is puzzling" that appreciation has "continued unabated" in some markets, despite the end of falling rates, Mr. Albinson said.

There has also been a hard-to-miss increase in private-sector anxiety.

In the survey of commercial lenders, conducted by the Philadelphia consulting company Phoenix Management Services Inc., only 39% said they did not believe a bubble existed; 15% said they were unsure.

In the second quarter of last year, less worry was expressed in response to a question about whether a real estate bubble was likely in the next six to 12 months. Only 22% said it was, while 42% said it was unlikely, and 30% said it could go either way.

"We started to see some negative" opinions about real estate "a couple of quarters ago," E. Talbot Briddell, a managing director at Phoenix, said in an interview. But few of the people who now see a bubble say "it would have any major impact on the economy in general," he said.

The lenders were surprisingly bearish, but for other reasons, according to the survey - the budget and trade deficits, the war in Iraq, and sluggish job growth. Sixty percent said a recession was "not at all likely" to begin this year.