Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

Detecting financial crimes can be painstaking work. Bank investigators have to piece together a paper trail of transactions — a trail that in most cases is intentionally designed to avoid detection — out of a huge trove of data. It’s easy for important connections to get missed.

“It’s like the old cop shows where people would get the highlighter out and highlight that this thing over here is the same as that one over there,” said Michael Shearer, group head of compliance product management and compliance chief data officer at HSBC.

But combating money laundering is a lot easier when you have artificial intelligence in your corner, he says. You can find a single transaction that might be related to another payment or counterparty. And once an AI algorithm knows what patterns to look for, however tenuous, it can find them on its own.

“We’ve been able to see connections between seemingly unconnected networks of people, where only one fact links two networks — one fact within thousands of pieces of information,” Shearer said. “When the numbers get big, that’s impossible for a human today, but pretty trivial for a machine to do.”

Humans have dreamed of creating machines capable of simulating thinking and feeling since antiquity, and the advent of digital computers in the 20th century made countless computational tasks fast and routine. But it’s only in the last decade or so that computers have become capable of learning and adapting, greatly expanding the range of tasks they can reliably and accurately perform.

AI’s core competency — as of right now, anyway — is its ability to comprehend and spot small changes within a seemingly infinite pool of data. That may seem quaint, but there are countless applications for that capability in the banking industry, and many banks are already putting AI to work. AI can monitor thousands of transactions per second and compare them against normal patterns to identify fraud or other irregularities,

AI can shape customers’ experience with a bank as well. It can sift through years’ worth of customer transaction history and activity to inform financial advice — perhaps a customer is making more money, and the bank can suggest opening a Roth IRA. AI is similarly able to recognize customer patterns and use that information to show them products and services they might be interested in and not showing them the ones they probably aren’t.

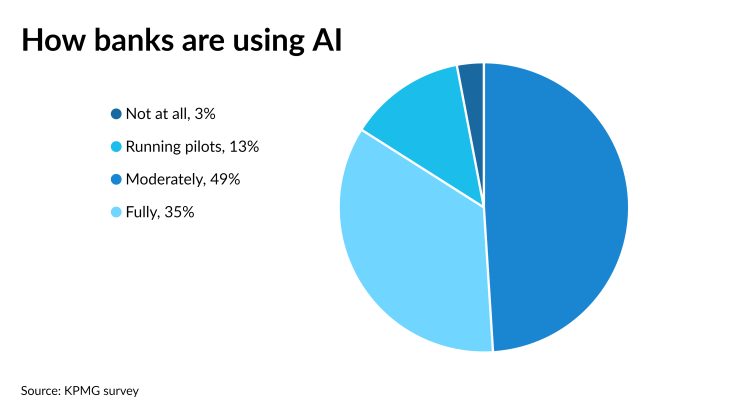

But while banks’ adoption of AI is broad, it isn’t particularly deep. That is in part because of prudence and caution, regulatory barriers and uncertainty about the efficacy of the technology. That caution could result in the banking industry remaining strong and competitive for years to come because it didn’t buy AI’s magic beans. But it also carries the risk that the banking industry could get left behind.

State of the art

The companies that lead in the development and use of AI are Big Tech: Google, IBM, Amazon and Microsoft.

But banks are a logical consumer of that technology, because the banking industry is teeming with data — balances, transactions, interest rates, loan performance, market fluctuation and risk are all quantifiable data points that constitute a complex ecosystem that is difficult for human beings to comprehend.

Banks have been interested in AI for years.

“I would say banks are in the upper tier in terms of AI innovation,” said Darrell West, vice president of the Brookings Institution in Washington and the author of several books on AI.

But a large swath of traditional banks — especially smaller banks — remain skeptical of AI. In a recent survey from KPMG, 75% of financial services business leaders said they think artificial intelligence is more hype than reality.

That could be for many reasons: too many news articles about it (this one included), too many vendors slapping “AI” on software that doesn’t qualify under any definition of artificial intelligence. Some may have no experience with it. Some may feel that all the disruptions of the pandemic have left them with scant energy and resources to invest in experimenting with new technologies.

Álvaro Martin, head of data strategy at BBVA, said that the bank is mindful not to rely too heavily on AI in its customer interactions because the result can be alienating.

“At some point, it might become even creepy for some people,” he said. “So you need to make sure that people understand what you’re doing, how you’re dealing with their data. And eventually create these seamless flows in which things just happen and customers are happy.”

Agnel Kagoo, advisory principal in financial services at KPMG, said bankers’ skepticism could stem from the fact that their experiments with AI have had no tangible results.

“We’ve seen a lot of organizations embrace AI and start to work on it,” he said. “But they have been in continuous experimentation mode, so nothing has really gone into production to drive through business value in terms of new revenue growth, efficiencies or better recommendations. So there’s a lot of money going into it, but no return coming up.”

But there is also a cultural and generational reluctance in the banking industry to count on an AI-centric future, Kagoo said.

“Not everybody in the organization is bought into it because there are varying levels of literacy,” he said. Some banks are trying to help everyone to understand what AI is, the pros and cons of it, why it is OK, and why it is not the be-all end-all, he said.

And some of the people using AI in banks — the people who create statistical models, for instance — may not see it as anything noteworthy, said Tim Cerino, AI leader for financial services at KPMG.

“When we speak to folks who are doing quantitative finance and financial engineering, or credit default monitoring, some have said, Isn’t this just old wine in new bottles?” he said. “We’ve been doing this stuff for years. They may take an underwhelmed-sounding perspective.”

But those banks buying into the promise of AI are finding several areas where the technology is making hard tasks easier and routine tasks faster.

Alexa, follow the money

Uncovering and combating money laundering is a prime example of where AI can help make a difficult task simpler. And in the case of HSBC, the bank has found that it can use two complementary AI approaches to detect money laundering — supervised and unsupervised learning.

Supervised learning is where software is taught to look for particular types of behavior by being fed examples of those behaviors. Unsupervised learning, by contrast, gives the AI software a baseline of activity and directs it to identify novel or unusual behavior. The two approaches together make recognizing patterns and linking networks faster and more precise than a simple rules-based approach, Shearer said.

“It makes the front-end machine one of your best investigators,” Shearer said. “You can distill the art of what a great investigator is looking for into an algorithm that the machine learns. Then you can apply that algorithm across your entire population; it’s like a force multiplier for your investigators.”

Banks have been experimenting with the use of AI in anti-money-laundering work for years, but in most cases they are reluctant to put those systems into production for fear of regulatory fallout.

In 2018, the Federal Reserve, Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and Financial Crimes Enforcement Network issued a statement that gave banks cover to at least pilot the use of AI in anti-money-laundering efforts. But the regulators have not given full approval to put such systems into production. They also haven’t promised that if a better-tuned program finds more real cases of money laundering, banks won’t be penalized for that.

Sultan Meghji, the inaugural chief innovation officer at the FDIC, said regulators are aware of the many potential uses for AI, and sees the technology as an opportunity to make banks more effective and responsive.

Meghji, who joined the FDIC in February after serving as CEO of the cloud-based core banking software company Neocova, said AI can be divided into two spheres: probabilistic and deterministic.

Deterministic AI applications are ones where a given input results in a given output, and the results are repeatable and the mechanism demonstrable. Probabilistic AI is more like the AML applications described earlier — flagging certain transactions that have a higher probability of being important, for example.

Deterministic AI applications are more likely to get the blessing of regulators, Meghji said, because the inputs and outputs are foreseeable and predictable. Probabilistic applications result in a range of possible outputs, which if left unchecked by a human could result in a false result — flagging the wrong transaction as fraudulent, say.

“I like being able to say, ‘Put A in, you get B out,’ and you can explain how you got there,” Meghji said. “If you can’t do that, then I worry about your ability to implement technology.”

But regulatory concerns can cut both ways. Banks may be hesitant to adopt AI for fear of regulatory reprisal, but at least in HSBC’s case, its adoption of AI was in part a response to money laundering and sanctions violations uncovered by the Justice Department in 2012. That action caused the bank to forfeit $1.25 billion.

“We have invested heavily to bring our controls up to set a standard for the industry, and I think we’ve been very successful at doing that,” Shearer said. “The bank has a real ambition to be effective in how it manages financial crime risk.”

While AI can make mistakes, people can, too. One of the biggest advantages to AI over traditional transaction monitoring systems is that AI can look at much more information surrounding a transaction and come up with a more nuanced evaluation.

“The benefits of AI for us are about the granularity of the detection process,” Shearer said. “We can be a lot more targeted about what we are looking for using a machine learning approach than we can be with rules, which catch a lot of behavior that isn’t of concern.”

An AI-crafted customer experience

Banks have also found that AI is effective in shaping the customer experience, using customer data to offer personalized interactions or just-in-time advice. TD Bank Group acquired the AI software company Layer 6 in 2018 for precisely this reason.

Layer 6’s technology can access customers’ transactions and account balances and identify trends — if it sees that a customer might overdraft, it will send the customer an alert, for example. But the full potential of AI in enhancing the customer experience has not yet been realized.

“It’s still early days,” said Tomi Poutanen, chief AI officer at TD Bank Group. “There’s a lot of work in just being able to make AI work in a big enterprise and building up a platform that can have a flywheel effect where you build models and then you accelerate the development of those models. But it’s been gratifying to see how valuable advanced machine learning algorithms can be in retail banking and also in our wholesale initiatives.”

AI can also provide some financial advice to customers. BBVA, for one, has been using AI to predict consumers’ financial movements and to tell whether they’ve missed a payment or funds have been wrongly diverted.

“Financial health is a really important strategic priority for us,” Martin said. “It’s all about making sure that our customers understand their finances and then we’re able to help them improve them.”

Mike Abbott, head of banking at Accenture, said that AI’s ability to look at customers’ current and past activity across channels and business units can help banks understand customers’ needs and solve their problems.

“AI should be the equivalent of a digital brain,” Abbott said. “It should be the best universal banker you have. If you think of what great branch managers have been able to do for a hundred y

ears over time, that’s ultimately what you want AI to do.”

AI is also being deployed by several banks in the form of virtual assistants, most notably Bank of America’s Erica virtual assistant, which launched in 2018. Erica has 19 million users, and answers about 12 million questions a month.

“When people have fairly targeted questions around things like moving money, status of transactions, paying bills, Erica does a really, really good job,” said Christian Kitchell, AI solutions executive and head of Erica at Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

Erica isn’t the only banking virtual assistant out there — TD Bank Group and U.S. Bank each have their versions as well. But there aren’t many, and part of the reason the service isn’t more universally adopted is that if AI makes a mistake with a customer’s money, it could do more harm than good.

That concern led Bank of America to test and retest Erica for more than two years before putting it in front of customers. The service is even trained to pick up on signs of frustration — such as a customer trying to do something multiple times on the bank’s app and logging out before finishing.

“Honestly, it’s really hard,” Kitchell said. “Being able to assimilate all of those different pools of data, profiles, metrics — all of those things have to be reconciled. We joke sometimes that AI is very sexy, but a lot of what we do is more akin to connecting pipes and gears. It’s an awfully ambitious task.”

Can AI make lending fair?

One of the more promising — and perilous — uses of AI is determining who gets a loan and under what terms.

Human beings' track record on credit decisions has been mixed. Racial and gender discrimination is illegal and has been for decades, but it still happens. And there is some research that suggests that AI could ultimately do a better job of assigning credit than people do.

Meghji of the FDIC said expanding credit access is precisely the kind of application that regulators want to support.

“We want every American to have access to best-in-class banking products and services,” Meghji said. “We want every small business, especially minority and women-owned businesses, to have access to amazing banking products and services that really help them. And these are places where AI has tremendous value.”

But West at the Brookings Institution a says there is a risk that AI could pick up on subtle customer behaviors that strongly correlate racial and gender identity and steer those customers away from some products and toward others — discriminating in practice, if not in principle.

“Human lenders are forbidden from using race, gender or marital status” in assessing an applicant’s creditworthiness, West said. “But with AI, you can find proxies for any of those things and use that to make lending decisions. So it’s a way to bypass some of the existing legal restrictions.”

For instance, an analysis of the magazine subscriptions a customer purchases or which stores they frequent could indicate a customer’s race or gender.

“They may not be incorporating race or gender directly, but you can certainly find factors that allow you to predict race or gender,” West said. “We want to build an inclusive economy that’s fair to everyone. And so we want the technology to correspond to basic human values.”

TD Bank Group has been using AI in its credit underwriting process since 2018, and the technology has become integrated beyond lending decisions to the management of the credit, the handling of nonpayment and the advice given to customers along the way, Poutanen said.

“We’ve seen that over and over again, where we’ve brought in machine learning algorithms that have replaced traditional and linear models, the machine learning algorithms are just way more accurate,” he said.

Machine learning is highly dependent on the information it is fed, and AI can learn racism and sexism just as people can. If a machine learning model used for lending was trained on a biased dataset — say, it only contained loan applications from white neighborhoods — it might favor white borrowers in its decisions.

Another fear is that AI used in lending could run amok, and come up with its own patterns of creditworthiness; that people with the last name “Smith” are high risk, for instance, by looking only at last names. Bank regulators have insisted that lending decisions can’t be made in a “black box” — every loan approval or rejection needs to come with a clear explanation of why that decision was made. Banks and fintechs have learned how to back up the reasoning behind AI lending decisions — the kind of deterministic AI applications that regulators can get behind.

“I strongly feel that machine learning is a better reflection on a customer’s behavior and financial state than, say, solely relying on a FICO score,” Poutanen said. “A FICO score is a lagging indicator of somebody’s financial state. Machine learning can incorporate a lot more information about the customer, look at their most recent data, look at their transaction behavior and account data. Those are more relevant signals of the behavior of that customer.”

Where AI fears to tread

For all of AI’s applications and for all of its gains, there are still far more things that only people are capable of. One of them is making big, important decisions — something AI can’t do on its own.

For instance, when a wealth management client is thinking about making a major change, “Nothing beats a conversation with a professional,” Poutanen said. “It’s no different than going to go see your family physician who deeply understands you. You want to be talking to a human doctor, not a robot.”

AI is also ill-equipped to handle emotionally charged situations or complex problems. Bank of America’s Erica virtual assistant is trained to intuit certain kinds of situations — a death in the family, for instance — and quickly pass the customer to a live representative.

And AI is also not yet capable of answering nuanced or complex questions, Kitchell acknowledged.

“There are certain areas where there’s a much better opportunity to provide the right level of service with a human, as opposed to a virtual assistant,” Kitchell said.

But Erica’s efforts aren’t wasted in those cases, he said, because the interactions with Erica are forwarded to a human agent who can see the context of what the client is looking for and help the person more quickly. And the simpler questions that Erica can handle are questions that a human doesn’t have to.

But because one of the things AI does well is to complete routine processes quickly, it can scale up a mistake faster than a human. And the question of legal liability in the event that something goes wrong — a creditworthy borrower rejected for a loan or charged too high a rate, an account wrongly opened or closed — it could make small problems much bigger than they might otherwise be.

“The more value you’re getting out of AI, the higher the liabilities are going to be,” said Andrew Burt, managing partner at bnh.ai, a Washington law firm focused on AI and analytics. “If you’re making lots and lots of decisions with a particular model, and one of those decisions is slightly discriminatory, you’re going to have a whole host of discriminatory decision making accumulate in a very short period of time.”

It’s important that banks think ahead of time about the legal and ethical risks associated with assigning tasks to unaccountable machines, Burt said.

“It is really expensive, time consuming and bad for society for companies — financial services in particular — to wait to ask for help until the bad thing happens, because usually someone has been harmed,” Burt said.

Burt added that banks adopting AI should recognize that those systems require tweaking and maintenance.

“What I get most concerned about for these large, analytically mature banks is that they’re resting on their laurels and not adjusting their model risk management practices to handle these new, much broader applications like chatbots and robotic process automation,” he said.

Facial recognition is another use of AI that could backfire on banks. There have been instances of facial recognition systems exhibiting bias after being trained on data that is not diverse. Many cities have banned their police departments from using the technology for this reason.

“Facial recognition is something I warn a friend or a client about every day,” said Patrick Hall, principal scientist at bnh.ai. “It’s very high risk at this stage. I would think very carefully about what the actual business benefits of using this technology are versus the risk.”

The risk of not taking a risk on AI

The engineer Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel, famously said in 1965 that computational capacity would double every year. That prediction became what is known as “Moore’s Law,” and while his prediction centered more on economics than technology, it has become synonymous with the idea that the things computers are capable of doing today will appear quaint when compared to their capabilities tomorrow.

There is every reason to believe that the capabilities of artificial intelligence and machine learning will similarly expand in the coming years to be able to perform all of the tasks that they are so conspicuously unable to perform today.

AI’s near-term advances seem to be in making human banking employees more efficient. They could help customer service representatives understand the context of the client’s situation — or, in the other direction, make sure that anything the bank tells that customer is accurate. The near-term future of AI is to be more integrated with the customer experience, BBVA’s Martin said.

“Ideally you would want as a customer to have seamless interactions between different channels, not just in terms of the information being connected behind the scenes for you, but also that if you get stuck in the process at some point, you want something to trigger so that eventually someone might ask you, ‘OK, do you want us give you a call?’ ” Martin said. “That kind of interaction is probably the way in which AI will most probably shape the way we interact with our financial institutions.”

From a regulatory perspective, a human-enhancing AI is the most fertile ground for the technology to grow into, Meghji said.

“AI is fundamentally about doing one of a couple of things very well,” he said. “Either it’s discovering something that you wouldn’t have discovered necessarily, or it’s learning how to put efficiency into your organization. So instead of one person only being able to do 20 transactions in a day, just imagine if they walk in in the morning and they can handle 100 transactions.”

Meghji worries with the application of all new technology, not just AI, banks, especially those that have old core systems, are not always adhering to current best practices.

“If you just layer on technology after technology after technology, and you aren’t thinking about the macro level value you’re trying to get out of that system, you can end up with a lot of unintended consequences,” Meghji said.

But there is a danger that banks’ reluctance to adopt AI — whether out of fear of legal and regulatory restrictions or out of prudence or some other reason — could leave them at a competitive disadvantage with challenger banks and fintechs.

“Not just in banking, but in all industries there is going to be some amount of disruption in terms of customer expectation management, financial institutions included,” Kagoo said. “If they do not continue to innovate and drive more hyperpersonalized services and meet their customer where they want to be met, they will lose out right in terms of market share, because the consumer is continuing to get used to, or be introduce to, these kinds of digital models and personalized service.”