Renewed export demand from China and tight domestic supplies are pushing up prices for corn, soybeans and wheat, boosting farmers’ fortunes and paving a path for a range of other rural businesses, including

Corn, for example, has traded above $5.50 per bushel this week — about 30% higher than the final week of October.

The positive trend could also lessen

“When prices rise like this — and it’s really a significant increase between just last fall and now — farmers’ cash flow changes for the better quickly,” said Shan Hanes, president and CEO of Heartland Tri-State Bank in Elkhart, Kan. “That’s ultimately good news for everybody around here.”

A majority of the $133 million-asset Heartland Tri-State’s loans involve agriculture — either directly to farmers or to businesses that work with farmers. When low commodity prices coincided with the

“It looked like maybe a depressing time was settling in,” he said.

Farmers

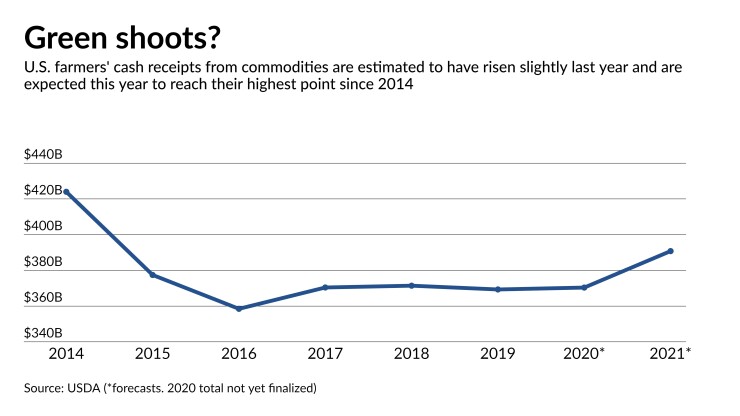

The Department of Agriculture said it expects farm income will total $111.4 billion in 2021. That would mark an 8% decline from last year, but solely because of the record government support in 2020. The current year projection would exceed by 21% the 2000-2019 average despite an expectation for farm subsidies to decline by 45% from last year, Seth Meyer, USDA chief economist, said at a virtual forum in February. That, he said, means cash income from crops is likely to surge this year.

Meyer said demand for U.S. crop exports is “remarkably strong” even “in the face of rising prices,” and the 2021 outlook is bright enough that the industry is on sound footing without lofty government subsidies.

Hanes said it will take time for farmers’ newfound prosperity to translate into spending on everything from new equipment to higher-quality fertilizer — and, by extension, lift the bottom lines of other agribusinesses in the rural Midwest. It will also take at least another year to ramp up crop production.

As long as export demand remains strong and supply is playing catch-up, prices could hold strong at their newfound levels, gradually leading to investments in land, tractors and other large-scale equipment that helps drive local economies. Rural banks finance those major purchases. Loan growth tends to follow.

Over the last five years, robust harvests steadily inflated supplies, putting downward pressure on prices. Then former President Trump’s administration raised tariffs on imports from China, fueling a trade war with the world’s second-largest economy and a crucial destination for U.S. crops. China levied new tariffs on American farm products in response, curbing U.S. exports and pinching farm incomes.

The

But trade tensions have eased and China is now in the midst of ramping up pork production amid a recovery from the pandemic — and needs U.S. crops to feed hogs. One result: Soybean, corn and wheat prices early this year have all traded at their highest levels since 2014, CME Group data shows. These crops form the foundation of the U.S. food supply; they are used in processed foods and to feed livestock.

The specter of credit quality challenges is fading along with the higher crop prices, and sentiment is rapidly improving, bankers say.

“When grain prices are up, everybody’s happy,” said Patrick Gerhart, president of the $36 million-asset Bank of Newman Grove in Nebraska.

“Overall loan demand is OK, but when prices are up and cash flow is strong, farmers pay down loans, too, so growth is not the first thing we see,” Gerhart said. “But credit quality has held up, and now it’s looking good. Our customers are doing well, and we’ll do well with them over time.”

A February survey of bank CEOs in 10 agriculture-heavy states across the Midwest conducted by economist Ernie Goss at Creighton University in Omaha, Neb., found a majority of bankers expect strengthening farmland prices and increasing agricultural equipment sales in 2021.

The survey produces a banker confidence index that measures outlooks for the next six months. In February the index produced a reading of 64 — anything above 50 points to growth — its highest level since March 2011, and up from January’s 60.

Dave Kusler, president and CEO of the $60 million-asset Bank of Hazelton in North Dakota, said beef prices are still under pressure — tied to the supply chain interruptions imposed by the pandemic — and cattle ranchers remain vulnerable early this year. Weather, he added, is always a wildcard for crop farmers; too little or too much rain in the spring is a perennial worry.

But overall, Kusler said, farm country is clearly on an upswing.

“Most people are really quite optimistic,” he said. “Compared to sentiment just last fall, things are much more positive."