Houston is proving that long-term appeal can outweigh short-term setbacks.

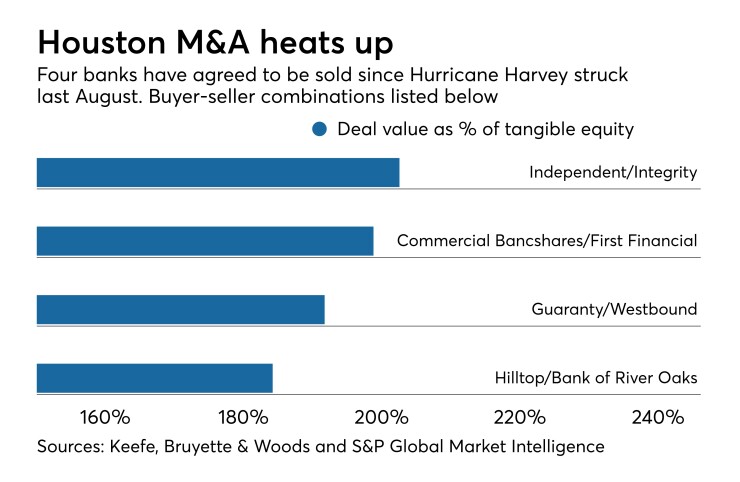

The nation’s fourth-biggest city has taken some hits in recent years, including a sharp decline in oil prices and severe flooding from Hurricane Harvey in August. In a sign that outsiders still have an interest, four Houston-area banks have agreed to be sold since Harvey.

While M&A activity paused briefly as bankers assessed flood damage — no deals were announced between Aug. 2 and Sept. 21 — consolidation accelerated quickly because of a strong desire to tap into the city’s bustling economy, industry experts said.

“Houston banks are doing well right now,” said Brady Gailey, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. “Harvey was definitely a scare and a lot of banks took special provisions in anticipation of loan losses, but that didn’t really happen. … It feels like Houston will be the heart of M&A in Texas for the next year or two.”

Texas has been one of the nation’s most active states for bank consolidation since the financial crisis, with 86 institutions agreeing to sell between 2011 and 2014, according to data from KBW and S&P Global Market Intelligence. Many of those banks sold at healthy premiums that topped 200% of their tangible book value.

The pace of consolidation slowed after the price of oil dropped sharply in 2014, bottoming out at around $30 per barrel in early 2016. That sent stocks for energy lenders tumbling and potential buyers and sellers to the sidelines; only 39 banks in the state were bought in 2015 and 2016.

The price of crude oil has partially recovered, rising by about 12% in the last year to more than $60 per barrel.

That improvement is encouraging renewed interest in Houston, said the leaders of Hilltop Holdings in Dallas, which recently agreed to buy Bank of River Oaks for $85 million in cash. The $9.7 billion-asset Hilltop began discussing a possible deal with the $439 million-asset Bank of River Oaks in early 2017, said Jeremy Ford, Hilltop’s president and co-CEO.

“There’s just a feeling of some comfort in the rebound of oil prices and the overall economic activity,” Ford said. Houston is “just more diversified.”

There are also shareholders at several banks who are looking to cash out, said Curtis Carpenter, head of investment banking for Sheshunoff & Co. Investment Banking. Shareholders at banks formed before the financial crisis, who have been sitting on their investments for about a decade, view favorable stock prices as a sign to move on, he added.

“We haven’t seen a market this good in a long time,” Carpenter said. “Some are saying, ‘Let’s take advantage of this.’ The best time to fly a kite is when the wind is blowing. And they see the wind blowing.”

Westbound Bank, based in the Houston suburb of Katy, agreed to sell itself to Guaranty Bancshares in Mount Pleasant, Texas, to give its shareholders liquidity and stock in a company with a history of paying a dividend, said Troy England, its president and CEO.

Selling will allow the $224 million-asset Westbound’s lenders to make bigger loans, absorb expenses tied to regulation and technology and add consumer products, such as mortgages, that were very expensive to offer due to compliance costs, England said.

“To compete in this market, you need a larger loan authority,” England said. “Liquidity is becoming an issue for banks throughout the country, and Houston is no different.”

Guaranty and Westbound briefly tabled their discussions when Harvey struck to “see how the hurricane played out,” said Ty Abston, the chairman and CEO of the $1.9 billion-asset Guaranty.

Houston has always been part of Guaranty’s strategy, so management did not have “a second thought about entering that market” despite Harvey’s damage and the potential of more natural disasters, Abston said. Because of Harvey, Guaranty took a deeper dive into Westbound’s loan book to make sure it was aware of any credits affected by the storm, he said.

“It has been remarkable how resilient and strong [Houston’s] economy is,” Abston said. “It is much more diversified than it is given credit for.”

Banks weathered Harvey better than initially expected, recording a total of $1.4 billion in hurricane-related provisions that covered Harvey and other storms, according to Autonomous Research. Stock prices for Houston’s banks bounced back to pre-Harvey levels by late September.

The low figure largely reflects the fact that the flooding spared most commercial structures, industry experts said. Most banks in Houston sell their mortgage originations.

“You saw some banks in the third quarter take some provision in anticipation of having some problems loans, but those generally haven’t been needed,” said Brad Milsaps, an analyst at Sandler O’Neill. “I think, in general, the underwriting was better and they were doing business with commercial customers that had the wherewithal and deep pockets with insurance or [an] ability to fix problems on their own.”

“M&A just needs buyers and sellers to have confidence in their markets,” said Matt Olney, an analyst at Stephens. “A natural catastrophe can temporarily remove the confidence, which results in a pause. Had the Harvey losses been more severe, then the pause could have been longer. … Conversely, more severe losses could also potentially result in greater rebuilding opportunity.”

Independent Bank Group, which has bought two Houston banks since April 2014, began working on its latest deal in the area a week after Harvey struck, said David Brooks, the McKinney, Texas, company’s chairman and CEO. He visited the city to check on the $8.9 billion-asset company’s branches and took Charles Neff Jr., president and CEO of Integrity Bancshares, to lunch. During that lunch, the executives decided to work on a merger.

The executives had a good sense of their banks’ exposure to Harvey within two weeks after the storm passed, Brooks said. They announced the merger in late November.

“If anything, the hurricane and the vibrancy and the ability of Houston to bounce back so quickly from a hard blow was an indication of how strong the market was,” Brooks said.

Consolidation will likely to continue around Houston, where nearly 100 banks hold almost $241 billion in deposits, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Energy remains an important part of the economy, though industry experts said the city has diversified in recent years.

Port Houston has seen increased traffic and the Texas Medical Center is world renowned, England said.

The storm likely addressed other issues in the economy.

Carpenter said some of his clients were struggling with loans to hotels, but those businesses rebounded because rooms were needed as people waited to repair flooding homes. Insurance money and other funds are expected to boost deposits at banks, while rebuilding will spur construction.

A limited supply of locally based banks — only 44 institutions call Houston home — will likely keep pricing high for targets, said Brian Johnson, a managing director in the financial institutions group of Commerce Street Capital.

“Community banks appear to have come through the cycle pretty well,” Johnson said. “Houston, like other metro areas in Texas, is attractive given the growth prospects in addition to the growth expected to come post-Harvey. In-state and out-of-state banks view that as an attractive market and that’s spurring this consolidation.”