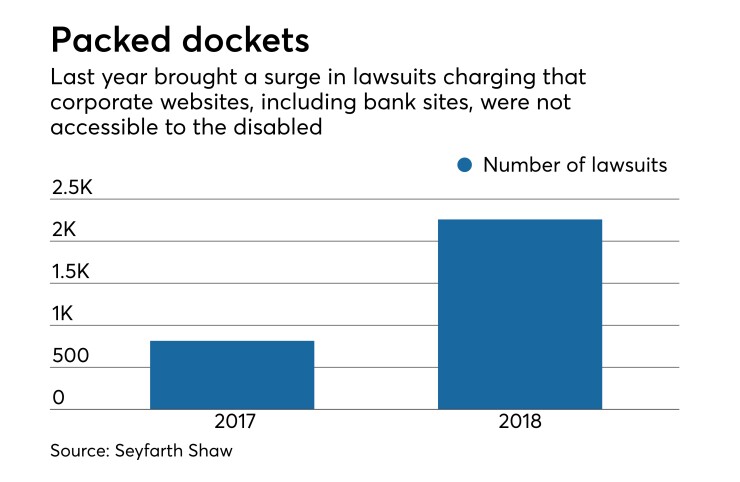

Lawsuits accusing corporations of operating websites that are inaccessible to consumers with disabilities skyrocketed last year. The trend shows no sign of slowing down in 2019.

Banks are vulnerable to these lawsuits, according to legal and technology experts, because they operate websites and mobile applications that promote products and services as well as let consumers conduct transactions. Both functions expose them to potential violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Just this year, at least 14 banks have been sued under the ADA in federal courts, according to the law firm Seyfarth Shaw in Sacramento, Calif. Defendants include Capital One Financial and Bank OZK in Little Rock, Ark.

Across all industries,

Attorneys expect these types of lawsuits to persist, largely because many recent judicial rulings have set precedents in favor of plaintiffs, said Kristina Launey, an employment lawyer at Seyfarth Shaw who advises companies on ADA compliance.

“The lawsuits are going to be increasing exponentially,” she said.

California is also likely to become a hotbed for the litigation this year due to a recent federal appellate court ruling in the state that was favorable to plaintiffs, said Tim Toohey, an attorney at Greenberg Glusker in Los Angeles. In that case, the court ruled against an argument by Domino’s Pizza that it could not make its website and app accessible because the

“The decision is likely to provide further encouragement” to plaintiffs, Toohey wrote in a

Even with the legal trends favoring plaintiffs, some bank executives choose to pay the costs of a legal settlement rather than make the financial investment needed to fix their websites, said Mark Shapiro, president of the Bureau of Internet Accessibility, a technology consulting firm in Providence, R.I. That is a mistake, he said.

“If you settle with them, it’s a short-term resolution, but you’re susceptible to other cases,” Shapiro said. “It’s not a smart thing to do.”

The steps banks need to take to minimize the risk of being sued are no secret. Several state banking associations, including those in

Websites and mobile apps must be accessible to consumers whose vision, hearing and mobility are impaired, Shapiro said. Helpful features include audio transcripts of written text, large font sizes and the ability to scroll through a page using a keyboard instead of a mouse.

All of those upgrades can help the disabled view, hear and access a bank’s content, he said.

“In many cases, these are not bogus lawsuits,” Shapiro said. “They are very legit cases.”

Bank management must also be mindful that if a website or mobile-based marketing promotion contains audio or video, they could potentially violate the ADA, Shapiro said. That is because the visually impaired, for example, may not be able to see the information that is conveyed and are thus excluded from the promotion.

“If you post a video for a promotion for taking points off your mortgage, if someone is colorblind and can’t see or read that, they’re excluded from the promotion,” Shapiro said. “You are discriminating against them.”

The cost to audit a bank’s websites and other technology for ADA compliance can run between $5,000 and $50,000, depending on the bank’s size, Shapiro said. The additional expense to remediate the technology would be much more.

To be certain, many banks have made a concerted effort to improve access for disabled customers—not just in the design of their technology platforms, but also retrofitting branches and ATMs, making it

Fifth Third Bank in Cincinnati, in one example, created a high school transitional program “that allows individuals who just happen to have a disability the opportunity to gain skills so they can go out and be active members of society,” Mitch Morgan, the bank’s manager for diversity and inclusion, told American Banker last year.

But banks and credit unions continue to be sued over website issues. And, in some cases, financial institutions have fought back.

Consider a lawsuit filed in February 2018 against Amalgamated Bank in New York. The plaintiff, Eugene Duncan of Queens, N.Y., alleged that he could not access the bank’s website because he is legally blind. Amalgamated responded in a court filing a month later that it was “ready and willing” to help Duncan access its services through other means, such as telephone banking, “but Plaintiff never asked for or sought any assistance.”

Duncan is “a serial plaintiff who filed this lawsuit to try to extort a monetary settlement,” Amalgamated said in the filing.

Amalgamated also said that the website of Duncan’s two law firms also did not comply with the ADA. It included a screenshot of both firms’ web pages in a court filing.

What happened next between Amalgamated and Duncan was not revealed in court. But six months after the bank submitted its response, the two sides agreed to a settlement. Financial terms were not disclosed.