Fintech companies like to say they’re democratizing finance, helping the little guy escape the high fees and elitist practices of the big banks.

Many fintechs offer apps and services that help people save, budget, get low-rate loans, reduce their debt and the like.

But the financial services analyst Karen Shaw Petrou forcefully argues in a paper published Monday that fintechs also pose serious risks that policymakers must address.

If not more thoroughly regulated, tech and fintech companies could create financial products that are more elitist than those traditional banks offer today, she argues. The flip side to the great promise these companies offer could be new forms of bias, threats to data privacy, security violations, misleading marketing and even systemic risk, according to Petrou.

As Congress and other policymakers examine big tech companies like Facebook for privacy, antitrust, cybersecurity and political-integrity weaknesses, they should also review the potential impact on economic equality and systemic safety as these companies delve more into financial services, Petrou said in a recent interview.

“My goal with this paper is to get finance on the agenda so that solutions can be put on the table because the real lesson we learn over and over again in banking is that retroactive consumer protection leaves a lot of badly hurt, vulnerable households in the ditch," she said. "It needs to be thought of now, before these products become even larger and more dominant in the financial system.”

To be sure, fintechs and challenger banks accuse banks of failing to protect their customers' best interests and of gouging customers living paycheck to paycheck with fees that make their financial lives impossible. They also say they are heavily regulated by state bank regulators and federal authorities such as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The real risk, from a fintech point of view, is continuing the status quo.

But Petrou, co-founder and managing partner of Federal Financial Analytics, is a veteran observer of banking in politics who has a history of insightful reads on the operational, reputational and political pitfalls that often lie ahead of banks (especially big ones), secondary markets, lawmakers and regulators.

If anything, her views will add to a brewing argument over the future of financial services, providing a counterbalance to the feel-good idealism that drives a lot of innovation today.

“I am all for technology,” Petrou said. “But I spent a lot of time when I was a student at MIT studying tech policy, and there is one after another example of seemingly promising technologies with terrible, unintended consequences.”

Bias and discrimination

In the worst-case scenario, big-tech companies and fintechs could discriminate against lower-income households, people of color and people with disabilities — behaviors that banks have been punished for and prevented from doing through fair lending and disparate-impact rules.

One example of the type of tech-related risk she worries about is the recent experimentation with facial recognition.

“It’s astonishing to me that

Facial recognition systems are only as good as the models they are built on, she noted. There have been numerous examples in consumer and security products where systems failed to recognize minority faces because of insufficient data or faulty programming.

“When these models are built by white men, they’re going to think like white men," Petrou said. "That’s one of the reasons why facial recognition does not work well on minority people.”

Another example is the kind of predictive modeling tech companies use for employment ads that end up only being offered to white men.

“We’ve seen a lot of this risk in nonfinancial technology based on big data and other very powerful techniques,” Petrou said. “We are taking a tremendous risk assuming that none of that would be used in financial product delivery or have a bias impact. It’s almost certain that some of it will and there will be bias unless policy intervenes quickly to prevent it.”

Another interesting case is Discovery Bank, which plans to launch in South Africa in March as a “

Petrou questions the wisdom of this.

“It’s unclear to me that people who smoke don’t pay their bills,” she said. “Clearly, people who live in dangerous neighborhoods aren’t likely to go out for a jog. It’s not going to happen because they don’t want to die.”

People who work three jobs can’t necessarily take 10,000 steps a day, and they may not be able to afford to drink carrot juice or eat organic foods.

“These are extremely judgmental measures of healthy living,” she said. “That’s implicitly very discriminatory if some elite view of what is good behavior is used in allocating credit based on it, or pricing deposits or offering securities. It’s a very slippery slope to a tremendous amount of disparate treatment.”

Current consumer protection rules might be inadequate to deal with such products, Petrou said.

“The models are opaque, the assumptions are hidden,” she said. "It’s already difficult to prove disparate impact, and this would be far more opaque.”

In this same vein, Petrou also worries about online lenders that use artificial intelligence in their underwriting and include data such as SAT scores in their decisions.

Some fintechs unabashedly go after wealthier segments like HENRYs (high earners, not rich yet).

“If it’s a business-model decision, that’s one thing, because that’s fair,” Petrou said. “As long as it’s not overtly discriminatory, you can target products based on wealth. When it turns to only white wealth, that’s where I get worried. And how will we know?”

Invasive analytics

Big tech companies that integrate finance with commerce, media and other types of business expose consumers to “misrepresented or complex products that put financial security at grave risk due to the absence of critical safeguards such as capital reserves, clear disclosures, transaction-audit and error-correction systems, conflict-of-interest restrictions, and even [federal deposit] insurance on products any consumer would consider a bank account,” Petrou wrote in her report.

One specific danger of a company like Amazon getting into finance is the possibility of analytics-based price manipulation. A consumer might try to buy a pair of sneakers and be offered a more expensive pair of sneakers because Amazon knows how much money he or she has.

“It’s watching your payment speed, estimating your pain threshold, and all of a sudden prioritizing products based on what it thinks it knows about what you can afford," she said.

The U.S. has separated banking from commerce for decades, she noted, because of conflicts like these.

“I’m trying to say, let’s take a look before people get hurt,” Petrou said.

Remedies

Addressing these issues, Petrou said, needs to start with attention from Congress and regulators, who often talk about responsible innovation.

“But if you push them, as I have, and ask what that means, nobody knows,” she said. “They’re ‘monitoring.’ Everybody’s running around monitoring. Can we monitor Amazon?”

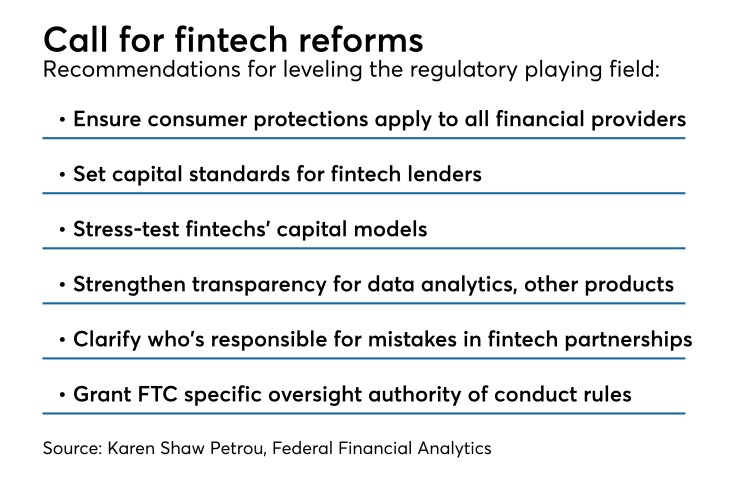

The same principles around illegal, improper, deceptive or confusing practices that are applied to regulated financial institutions need to be applied to nontraditional providers, Petrou said.

“If we have an asymmetric safety and soundness and consumer protection framework, which now we do, it will be a lot more profitable to offer product outside the reach of all the rules,” she said. “And a lot of people are going to get hurt.”

Fintechs such as online lenders often say they are regulated by national and state authorities. Petrou argues this is not enough.

“They’re regulated in certain consumer protection areas but not in others,” she said. “Do they have money at risk when they make loans? No, because they don’t have capital. Do they have servicing capacity to support vulnerable borrowers who miss a payment? No. Are there clear protections against cross-marketing? No.

“I’m not suggesting that all fintech or big-tech providers are predators. They’re not. I am saying the absence of a meaningful, prudential and consumer protection framework favors bad providers and high-risk behavior.”

Innovation can indeed enhance inclusion, but only if critical safeguards are in place.

For instance, clarity is needed around who is responsible for mistakes in the providing of fintech products, and how able those entities are to remedy them. Transparency is also needed, she said.

“What do your models look at? When did you change them? What are their results?” she said.

Fintech models also need to be tested the way the Federal Reserve requires banks to test and validate their capital models.

“The burden of proof needs to be on the provider, not the hapless customer,” Petrou said.

Reporting requirements for personal and small-business loans that mimic the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act would help provide transparency, she said.

Clear codes of conduct need to be established and disclosed in a way that make the provider liable to the Federal Trade Commission if the codes are violated, Petrou said. These should cover how products are packaged and on what terms financial products are offered and priced.

And the codes need to be enforceable. Otherwise, companies will end up offering what is most profitable to them, without taking the time to worry about the customer.

“The enforcement mechanism has got to be powerful and prepositioned,” Petrou said.

Banks are not perfect, as fintechs will eagerly point out. There are high fees, product structures that adversely impact low-income people and scandalously bad practices.

“The difference is that they can be and are punished,” Petrou said. “A lot of rules don’t apply outside the banking system.”

If a large fintech or tech company were to create fake accounts, for instance, “what rights would you as a consumer have? None.”

The overall risks are to economic equality, Petrou said.

“The U.S. is already profoundly unequal,” she said. “Let’s not make it any worse.”