The Paycheck Protection Program debuted slightly more than a year ago with a flurry of applications for emergency small-business loans and a well-documented crash of the Small Business Administration’s overworked portal.

The SBA has since approved about 9.6 million loans totaling more than $755 billion.

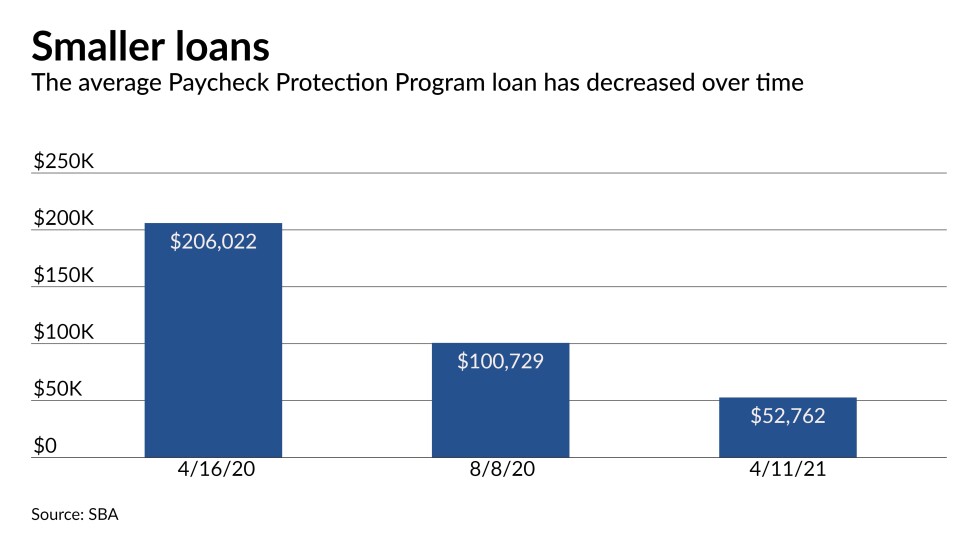

The initial $349 billion of funding barely lasted two weeks, forcing a shutdown on April 16, 2020. Congress eventually allocated more funds, allowing the program to reopen and operate from April 27 to Aug. 8.

A new round of PPP began Jan. 11, though the program has gone through a number of changes since its inception. For one, a greater emphasis has been placed on smaller loans to smaller businesses.

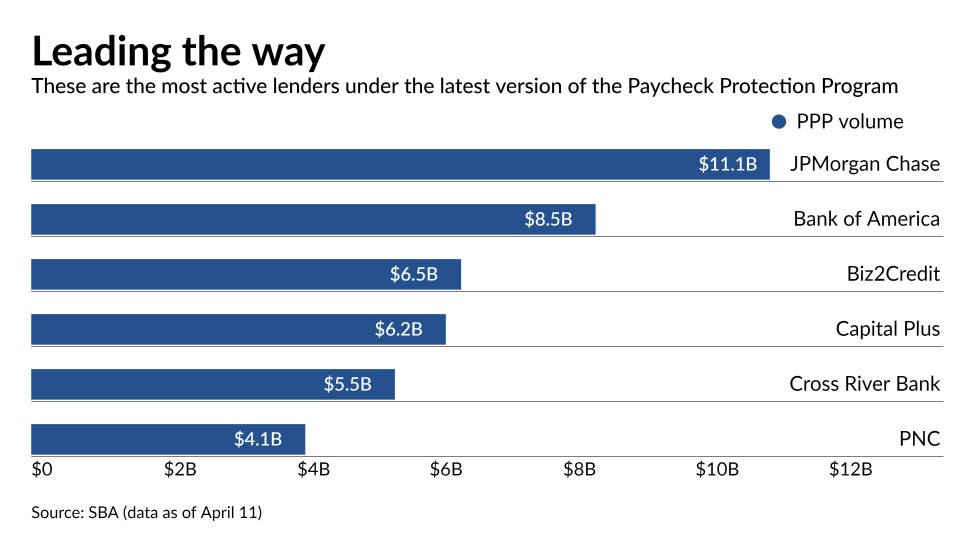

The PPP has changed in several other ways, too. The latest iteration of the program allows existing borrowers who can demonstrate ongoing pandemic-related hardship to apply for a second round of funding. And a number of community banks have significantly increased their involvement compared with the PPP’s earliest days.

Here is an outline of five ways that the PPP has evolved.