For Asian-American banks, the pockets of investors appear to reach even deeper than the banks' credit problems.

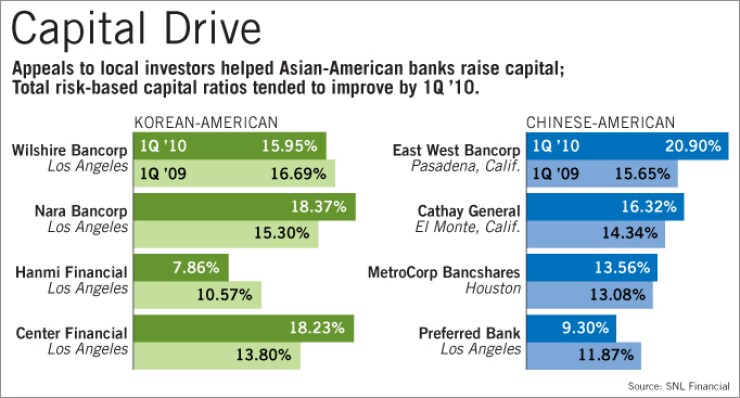

The largest Korean-American and Chinese-American banks, primarily clustered in Southern California, are successfully raising capital, surprising competitors with last-minute infusions even while some operate under regulatory orders.

The reason for the capital boom?

It's largely a function of proximity to their ethnic markets. And their loan portfolios were concentrated in commercial real estate, so when the market fell apart in California, they needed to raise capital to stay alive — and their communities delivered.

"It was very surprising to Korean-American banks as well as mainstream investors," said Alex Ko, chief financial officer at Wilshire Bancorp Inc. in Los Angeles, the largest publicly traded Korean-American bank in the United States, with $3.5 billion of assets.

Ko was referring to a bank he would not identify that he said raised more than $60 million just before it was set to be closed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., as he and others waited to hear about their bids for the bank. "It gives the signal for how much capital can be raised … if management can talk to investors effectively."

Yet the need for capital has been at least as great as the efforts to raise it, as Asian-American banks have experienced significant credit deterioration over the past several years while the California real estate market tanked.

Six of the eight largest Asian-American banks in the United States have announced or completed multimillion-dollar capital-raising efforts in the past year.

Not all of the banks are raising capital to shore up balance sheets; a few are doing so to acquire weaker rivals.

Because bankers with both goals have succeeded, the anticipated widespread consolidation among Asian-American banks has not taken place — some banks considered to be ripe for acquisition have raised enough capital to live another day. The consolidation in the market has occurred with a few pickups of failed banks.

Both groups have been successful because the weaker banks are tapping into the ethnic pride of local investors who want to keep the bank alive. The stronger ones have caught the attention of institutional investors as a likely spot for good returns.

"There is a lot of community support for ethnic-focused banks in their respective communities," said Julianna Balicka, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc.

Analysts were surprised, for example, when Los Angeles Saehan Bancorp on March 9 announced a $60.6 million privately negotiated capital infusion, barely beating its March 8 regulatory deadline to raise capital at its bank.

That effort helped the $649.3 million-asset Saehan Bank exceed capital requirements outlined in a consent order. Most of the capital came from individual Korean investors who were familiar with the bank.

More recently, one of the largest Korean-American banks, Hanmi Financial Corp. in Los Angeles, announced May 25 that it would receive as much as $240 million from Woori Finance Holdings Co. Ltd. in addition to $120 million raised in a stock offering.

If the infusion from Woori is approved, the $2 billion-asset Hanmi will exceed the regulatory requirement to raise $100 million by the end of July for its undercapitalized Hanmi Bank.

Woori, a majority of which is owned by the South Korean government, filed its request for deal approval with U.S. and Korean bank regulators on June 24.

Chinese-American banks also have been able to raise capital recently with the help of their close-knit communities.

Los Angeles Preferred Bank said June 21 that it raised $77 million through a private preferred stock placement, slightly more than the $70 million anticipated — even as the bank operated under a consent order.

The $1.4 billion-asset company said more than half of the funds were raised by directors, officers and friends and family of the bank.

On the flip side, healthier Asian-American banks have been capturing investor interest, but mostly from larger institutional investors.

"Banks that are not in trouble but are raising capital are doing so to be offensive," Balicka said. "In those cases, there is a lot of capital coming in from institutional investors.''

One of the first Asian-American banks to recently test the capital market was Los Angeles-based Nara Bancorp Inc., which raised $86.3 million in common stock in October. Alvin Kang, president and chief executive officer of the $3.1 billion-asset company, said in an interview that more than 70% of the capital was raised from institutional investors.

Even though the capital was not critically needed, Kang said the company wanted to be "opportunistic" and to be in position to benefit from what he thinks will be future consolidation.

The equity kicking into these banks signals a possible wave of consolidation that analysts have long predicted.

One of the most active acquirers among Chinese-American banks is the $20.3 billion-asset East West Bancorp Inc., which took over two failed banks after raising $249 million in July 2009 and $500 million last October. The company acquired Washington First International Bank in Seattle on June 11 and had snagged a close rival, Los Angeles-based United Commercial Bank, in November 2009.

Wilshire State Bank picked up a failed Korean-American bank, Mirae Bank, acquiring it with Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. assistance in June 2009. With the Mirae acquisition, Wilshire became the largest Korean-American bank in asset size, up from the third largest previously.

Ko said he would not be surprised if another Korean-American bank failed soon, though he predicted it would be some time before another whole-bank acquisition occurs in that market. "That type of deal is quite substantial and requires a lot of consensus between boards," he said.

Aaron James Deer, an analyst with Sandler O'Neill & Partners LP, said there has been less consolidation than was expected in the Korean sector partly because bank boards prefer to remain independent. "There's something to be said for serving on the board of a local banking institution. Some prestige, if you will," he said.

Further, Asian-American bankers said that until banks work through commercial real estate loan delinquencies, significant consolidation is unlikely to take place.

"The Korean banks were heavily into CRE with close to 70% [of their loan portfolio] or higher for some banks" in commercial real estate, Ko said. "Their biggest challenge is definitely the need to survive and manage through the credit cycle."