One of the nation’s largest credit unions is facing heated questions from a longtime member regarding a lack of diversity on its board of directors.

As the nation grapples with issues of race and social justice following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other Black people killed by police, some credit unions have

“The spotlight on racism has opened a lot of ears and a lot of minds,” said Jill Nowacki, CEO at Humanidei. “There has been a rise of listening sessions where credit union CEOs are hearing the stories of their Black employees for the first time, then conveying what they have learned to their boards.”

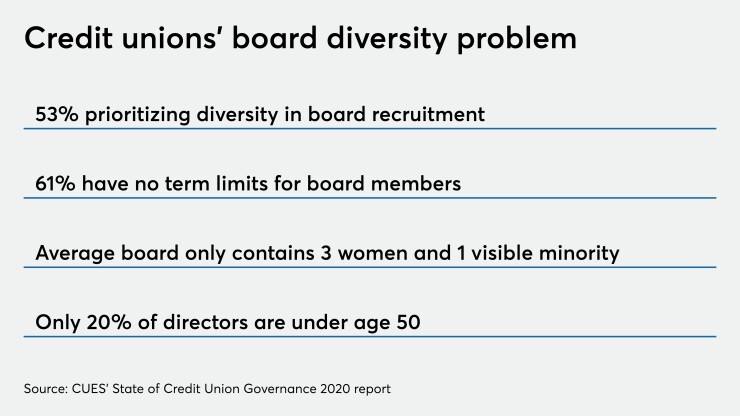

A lack of board diversity is not a new problem for the industry. Barely half of respondents to a recent survey from the Credit Union Executive Society, Quantum Governance and the Johnston Centre for Corporate Governance Innovation

One institution facing these challenges is SchoolsFirst Credit Union in Santa Ana, Calif.

SchoolsFirst Federal Credit Union, the nation’s fifth-largest credit union, is under pressure following a series of inquiries from a longtime member regarding the board’s diversity efforts — or lack thereof.

Barry Resnick and Narges Rabii-Rakin, friends and SchoolsFirst members for 40 and 20 years, respectively, began asking questions about the board’s nominating process earlier this summer when Rabii-Rakin was considering running for a seat on the panel. She struggled to find information about the process and had to reach out directly to SchoolsFirst staff for more details.

The credit union posts election information on its website in January but removes that content after the annual meeting in May. To be considered for a seat, members must submit a completed volunteer packet no more than 90 days before the annual meeting or be nominated via a petition signed by 500 members over the age of 18.

“The process is not very transparent, clear or open on how to become a board member — or even who the board members are,” Rabii-Rakin said. “Unless you’re very specific and deliberate, you’re not going to find out how to join.”

Though Rabii-Rakin was deterred by the lack of transparency in the election process, she said she is still interested in eventually joining the board. But as Resnick continued looking into the board, he discovered a lack of diversity he believes isn’t fitting with one of the nation’s most diverse regions.

Resnick had multiple email exchanges with a SchoolsFirst executive about the board selection process and subsequently

“I was shocked,” Resnick said. “All the legal letter did was confirm that these board members do not want to give up their seat.”

“I’m a member, it’s not like I’m some guy off the street,” he added.

SchoolsFirst representatives declined to be interview for this story but Mark Rapp, senior vice president at the credit union, said in an emailed statement, “While a photo of our board may not present an outwardly diverse appearance, these dedicated individuals are diverse in many imperceptible ways. That said, though, they and we know we can do more to represent diversity. And our board is committed to doing so over time.”

‘A disconnect’

SchoolsFirst is far from the only credit union dealing with these issues. A 2018 survey from the Credit Union National Association found 90% of credit union board members are white. The typical fortune 500 company board is 83.9% white, according to the Alliance for Board Diversity.

A lack of diversity on credit union boards, “presents a disconnect with the ethnic community we see in the country,” said Víctor Miguel Corro, CEO of Coopera.

For example, a homogenous board made up of mostly white directors may not understand the need for products or services that address the high costs associated with immigration, he continued. That could leave out a subset of membership, especially if a community’s demographics differ from that of the board.

There are steps credit unions can take to correct this.

Diversity "starts with the board itself,” Nowacki said. She suggested working with directors to determine what characteristics the current board of directors has and what qualities are missing from the panel’s ideal makeup.

Some institutions are also putting term limits in place, which Nowacki said can help ensure the board better reflects its currnet membership. A lack of term limits, she said, can create situations in which would-be directors who haven’t had the opportunity to serve are kept from contributing.

SchoolsFirst declined to comment on whether it is considering implementing term limits. Just 14% of respondents to the CUES/Quantum Governance study said their credit unions have term limits for directors.

On the other hand, term limits can also present problems for credit unions if there isn’t enough interest from members in joining the board. And smaller credit unions without the resources to invest in board recruiting strategies could also face challenges, along with institutions in less diverse geographic areas.

“This is a journey that may not have a clear finish line,” Corro said. “I usually call it a marathon without a finish line, because it’s something that you start, but that you continually evolve.”