One credit union's admission that it is merging over economic fears isn't likely to be the start of a trend, but analysts say mergers are likely to kick back up after slowing down somewhat this year.

The $90 million-asset Chesterfield Federal Credit Union said in a letter to members posted on its website that it would partner with Virginia Credit Union in part because it was “not confident that we could remain well-capitalized through another economic downturn.”

Overall the number of credit union mergers has slipped in recent years. An economic recession, combined with other pressures such as keeping up with technology, could spur some institutions to look for mergers.

“Bigger is not always better, but there are realities of operations that need to be considered,” said Michael Bell, an attorney with the law firm of Howard and Howard in Royal Oak, Mich., adding that he counsels CUs against waiting until it is too late to look for partners. “A healthy credit union will have a line of strong partners competing to do a business combination, but this changes dramatically when the credit union’s health slips.”

Being healthy right now was a factor in deciding to merger into the $3.7 billion-asset Virginia Credit Union in North Chesterfield, according to the letter posted on Chesterfield’s website. The letter, signed by Chairman Scott Zaremba, said that “the time to take this step is now, while our credit union remains financially sound and we have the opportunity to partner with a strong, local credit union.”

During the Great Recession, Chesterfield, which is also based in North Chesterfield, saw a large increase in deposits in a very short period of time, while loans and other income-generating products did not keep up, said Chris Miller, executive vice president who oversees marketing and IT. As a result, its net worth ratio plunged from being well capitalized at 9.34% at the end of 2008 to being just adequately capitalized at 6.96% at Dec. 31, 2012, according to call report data.

But even during a strong economy, Chesterfield has run into issues with keeping up with compliance and providing the products and services, such as mobile deposits, that members want.

“There are income-generating products that we do not offer to our members,” Miller said, adding the CU offers auto loans, credit cards and personal loans, and it relies on noninterest income, most often in the form of overdraft fees and interchange on debit cards. “Those are the things that keep our credit union afloat.”

Chesterfield FCU approached VACU about a year ago, and the two CUs have been working on due diligence ever since. The merger is subject to a vote by Chesterfield FCU’s membership at a special meeting in January.

Glenn Birch, director of public and media relations at Virginia Credit Union, noted that his institution did not seek the merger. He said VACU has not been actively seeking mergers as a part of its strategy for growth. Its most recent merger was of Sperry Marine FCU, a small credit union in Charlottesville, Va., in 2015.

“Chesterfield FCU reached out to us because they believe a merger is in the best interest of their credit union and membership,” Birch said. “We agree there is a good fit between our credit unions’ mission, membership and shared location.”

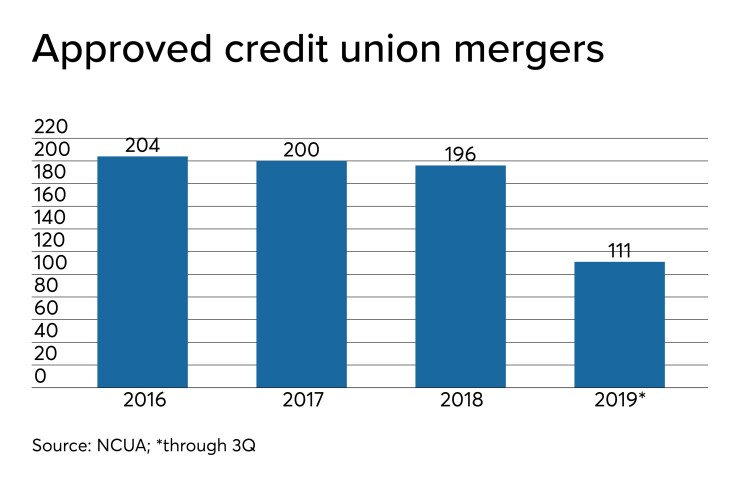

Despite the concerns of smaller institutions such as Chesterfield, the number of mergers has been decreasing over the last several years. The National Credit Union Administration approved 196 mergers in 2018, down about 4% from 2016. Through the first three quarters of 2019, the regulator has approved 111 mergers, putting this year on pace to be even slower.

Why the number of deals keeps slowing “defies all logic considering the increasingly difficult operating environment,” said Peter Duffy, managing director for Sandler O’Neill, which advises credit unions on merger-related activities.

Bell said not enough credit unions are looking for merger partners during what has been good economic times for several years.

Still, many credit unions are still facing the same issues and choices that Chesterfield had to contemplate.

“It is exceedingly difficult to offer good rates and fees to members, and it is exceedingly expensive to pay for technology, while also remaining compliant,” Duffy said. “When you put all those factors together, it is a big squeeze. The market is not giving in – people want lower loan rates and higher deposit rates, and don’t fee me or I will go to a fintech. It is an intense competitive environment and costs that are increasing, all the way up to Chase.”

Duffy believes the CU industry “may be turning a corner” with the pace and size of merger activities. From 2008 to 2018, the average size of a merged CU was $20 million in assets, while in 2018 there were four credit unions that were merged out with assets of $300 million or more. Sandler advised on two of those deals.

Last year, there were the announcements of the mega mergers of the $1.9 billion-asset

“What you are seeing occur is an indication that institutions are probably discussing more frequently what their path should be, and a precursor that there will be more mergers of all sizes going forward,” Duffy assessed. “If SunTrust and BB&T and are saying, ‘We are not big enough,’ then what are other institutions saying?

Duffy expects there will be “more deals and larger deals.” He said his firm is in about a half-dozen discussions with credit unions looking to merge and in three of those both sides of the potential merger are greater than $1 billion.

“That does not mean they are going to close, but what the larger institutions are saying is, ‘We don’t have enough in asset size, given how competitive things have gotten,’” Duffy said.