This story is the latest entry in Credit Union Journal’s special report on cybersecurity, which has run throughout the month of October. Additional coverage on this topic

Got a spare $1.8 million? Institutions that don’t have adequate cybersecurity protections may need that much or more to clean up after a cyberattack.

A

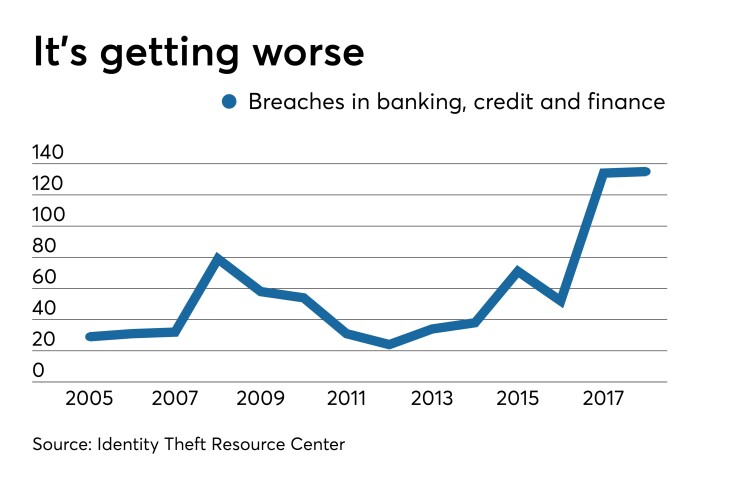

Falling victim of a cyberattack can be one of a credit union leader’s worst nightmares, and with data breaches increasing in size and frequency, financial institutions are more likely to fall victim than ever before.

The question facing credit unions is what to do when – not if – they are attacked.

“Most big incidents when they happen, people don’t think very clearly, so you’ll want to fall back on a plan so you can test it,” said Tom Kane, president and CEO of the Illinois Credit Union League.

Kane would know. About seven years ago, malware appeared on one of the league’s internal systems. ICUL immediately disconnected the infected device to ensure the threat couldn’t connect to anything else. As the league alerted relevant parties within the organization, IT personnel were called in to confirm that there was no bleed-over into the league’s wider network.

Ultimately, the virus was contained, the best possible outcome. But Kane said ICUL learned plenty of lessons as a result of the process.

For starters, he advised, credit unions need to look at their staff and identify who needs access to the core network and other sensitive member data – even if that means cutting some people out.

“Once I became CEO, they said that I didn’t need to have access to this anymore because I’m a vulnerability,” Kane said.

Though the threat amounted to nothing, Kane emphasized the importance of staying up-to-date with anti-virus protection and designing separate internal systems so that if one is compromised, the entire network doesn’t fall victim to a threat. That’s a feat more easily managed by larger credit unions compared to smaller ones due to structure and overall costs.

Aside from the actual risks that come along with a breach, credit unions must also account for the reputational risks associated with being the victim of a cyberattack due to lax security measures. Cybersecurity protection isn’t cheap, but “it’s the cost of doing business,” said Kane. The league spent between $2.5 million and $3 million to put defenses in place before the breach occurred, but a virus still got through because one system was slightly outdated. Since then, ICUL has spent as much as $300,000 each year making ongoing investments in personnel, systems and hardware.

Who ya gonna call?

If a credit union is breached, an institution’s response will scale depending on the type of attack. A small virus such as ICUL dealt with does not require attention from the National Credit Union Administration, but larger attacks that compromise sensitive member information could.

Lucy Ito, president and CEO of the National Association of State Credit Union Supervisors, suggested state-chartered shops also get their local regulators and law enforcement involved.

“That will enable credit unions to figure out [if] the breach they’re suffering is stand-alone or possibly part of a larger attack,” she advised.

Once a credit union conducts its incident response and wraps up any investigation, that’s when contacting members comes into play. Experts suggest CUs wait to contact consumers until after any investigation is completed so that intuitions have a better understanding of exactly what information was affected. Some partners, such as Visa, also have a time frame in which they require notification if any card data was stolen in an attack.

“If you know exactly what member information was exposed, that’s the members you need to contact,” said Robert Smith, information security officer at Tropical Financial Credit Union. “If you can't determine in a specific time frame if those members were or were not exposed, then you have to err on the side of caution where you have to notify everyone.

Individual CUs can also conduct threat tests to prepare for potential attacks, including sending a disguised e-mail to employees to gauge whether or not staff can discern between a threatening and non-threatening message. Tests also could loop in a review of roles and responsibilities, parties to notify, how to isolate compromised pieces of equipment and ensuring that the threat has not spread to other parts of the network.

Money matters

From a tactical perspective, 52% of attacks feature hacking while 28% utilize malware, according to the 2019 Data Breach Investigations Report from Verizon. And while attacks on banking and finance make up a small portion of the overall threat landscape, 71% of all breaches are financially motivated, Verizon reported.

“If a customer account is breached, the institution will probably have a hard time recovering those funds,” said Anthony Patti, a co-founder of Drawbridge Partners. “If there was a substantial amount of capital that was stolen, a lot of the times the institution is on the hook to make sure that a client’s funds are reimbursed.”

That’s been the crux of the credit union industry’s argument as it continues to push Congress for stronger data security protections: when retailers and others are breached and consumers lose money, their financial institution is left holding the bag.

Still, sometimes it’s possible for institutions to retain control of breached funds, but if they fail to do so then a credit union dons the reimbursement responsibility. Though that can be covered by cybersecurity insurance, that’s only when firms are covered by cyber insurance policies that cover human-based attacks such as phishing.

“There are a lot of cyber insurance policies that exclude the human element, so institutions need to be careful,” Patti said.