BROOKLYN, N.Y. – A Brooklyn credit union and a nonprofit have teamed up to address the effects of redlining.

Minority communities have long been discriminated against when getting mortgages and other financial services, particularly among black neighborhoods. Concord Federal Credit Union and Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation are working together to combat this by offering more affordable banking products and counseling to central Brooklyn, which is significantly under served by mainstream financial institutions.

Redlining isn’t unique to New York and happens throughout the country so the partnership between Concord and the Restoration Corporation could be replicated in other areas.

“There is a great need in Bedford-Stuyvesant and in central Brooklyn for financial services and products people can trust, rely on and afford,” Ronnie L. Brandon, president of Concord’s board, said during a launch event last week for the partnership at Concord Baptist Church of Christ in Brooklyn. “[We are] addressing the question of not what others can do for us, but what can we do for ourselves to build our community [and] to lift our community.”

Redlining is a discriminatory practice where a financial institution refuses some form of service, such as a loan or insurance, to an individual who is deemed to be a financial risk without any evidence to make that assessment, said Rachel Lovell, a professor at Case Western University who has studied redlining and its effects. Redlining targets people of color and those who are impoverished.

The practice of redlining can be traced back to the early 1930s where the the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and Federal Housing Administration systematically refused to lend to neighborhoods that were deemed too risky. White neighborhoods were rated as low-risk while black neighborhoods were labeled as high-risk, with the latter colored in red on maps. But the phrase was officially coined in 1960 by the sociologist John McKnight to describe this discriminatory practice of outlining communities that banks would ignore.

Although the practice is often associated with housing, communities that have been redlined suffer from higher rates of asthma and lead poisoning, poorer internet access and fewer choices for other businesses, such as doctors or grocery stores, Lovell said.

“Redlining is an unfortunate part of the fabric that capitalism is built upon that needs to go away,” said Keith Wright, who served for 24 years in the New York State Assembly, including as the former chair of the Housing Committee. “The people in power need to understand that redlining is not good for people in New York, and when you redline certain districts, it creates a local apartheid."

Redlining segregates neighborhoods, creating divisions that are “rife with poverty, rife with no access to capital, rife with bad schools, [and] rife with high crime,” which creates an unbalanced, unequal and unhealthy society, Wright said.

Concord was specifically created in response to redlining back in the 1950s, said Lori Llewellyn, an employee of the $10 million-asset Concord. The credit union served the central Brooklyn community, making loans and financial services more accessible to those rejected by banks and targeted by predatory lenders.

Despite the implementation of legislation in subsequent years, such as the 1968 Fair Housing Act, the effects of redlining still manifest today.

High levels of poverty are still present in central Brooklyn. Compared to the rest of the nation, Brooklyn consistently appears as an area with high poverty, high unemployment and low wage growth. According to a 2019 report from Brooklyn Cooperative Federal Credit Union, the area has a 23% poverty rate, compared to the national average of 15%. Brooklyn, which is 64% non-white, has a median income of $48,026, compared with $55,775 for the U.S., according to the report.

“You’re getting in the root of the banking system: That people of color are just not able to reap the benefits of real estate investment,” Wright said. “[B]eing denied access to credit, particularly mortgages, which offer substantial tax benefits, makes it nearly impossible for families in redlined communities to buy a home. And with predatory lending, which impacted thousands of families in New York City, people who owned a home suddenly found that the American Dream was pulled out from under [their] feet."

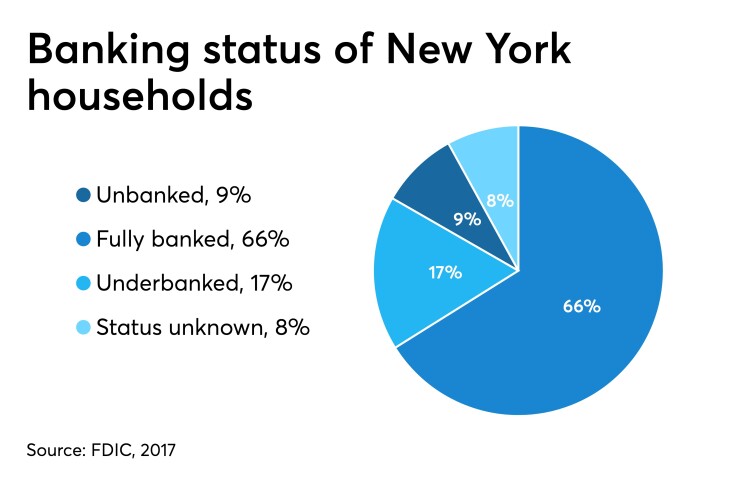

A fifth of households in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood are unbanked and nearly 30 percent are underbanked, according to John Dallas, senior financial counselor for asset building at Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, which is a community based center that provides services to help close the wealth gap.

Since many of these households are forced to turn to alternative financial services, including high-interest predatory loans, the Restoration-Concord partnership is looking to serve as a better option by offering financial counseling and coaching as well as accessible financial products.

The work between the two organizations will focus on referrals where Concord will offer financial products, such as affordable loans and savings accounts, and the Restoration Corporation will provide financial counseling and advice through its economic solutions center.

One of those products is a savings account that offers 1.25% interest annually. That’s much higher than the national average of 0.10% APY, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Concord expects that it could triple its size through the partnership.

Their goal is to have 100 individuals within the community take advantage of both institutions within the first year, Dallas said.

The partnership is part of the African American Credit Union Initiative, which is supported by Inclusiv and Citi Community Development. Concord is also participating in Inclusiv's new

Credit unions joining community organizations to combat the effects of redlining is something that others could try. That would fit with the industry’s ethos of people helping people, and credit unions have a history of supporting groups like the United Way, the Boys & Girls Club of America and other nonprofits that work to increase equality and address discrimination.

“That’s a great way to eradicate the effects of redlining in the future,” Wright said. “Where communities can pool resources collectively, certainly a lot of the problems that we’ve seen in the past probably would be eliminated.”