Credit unions need to take a long, hard look at their cost structures/operating expenses and find ways to reduce them while still providing high-quality services to their members along with competitive fees and product pricing.

It's a tall order, but that's the advice of industry experts and insiders interviewed for this Special Report: The Bottom Line.

They note that data on the financial health of credit unions from the National Credit Union Administration paints a complex picture of extraordinary growth in members, loans and net income, but modest or weak efficiency figures.

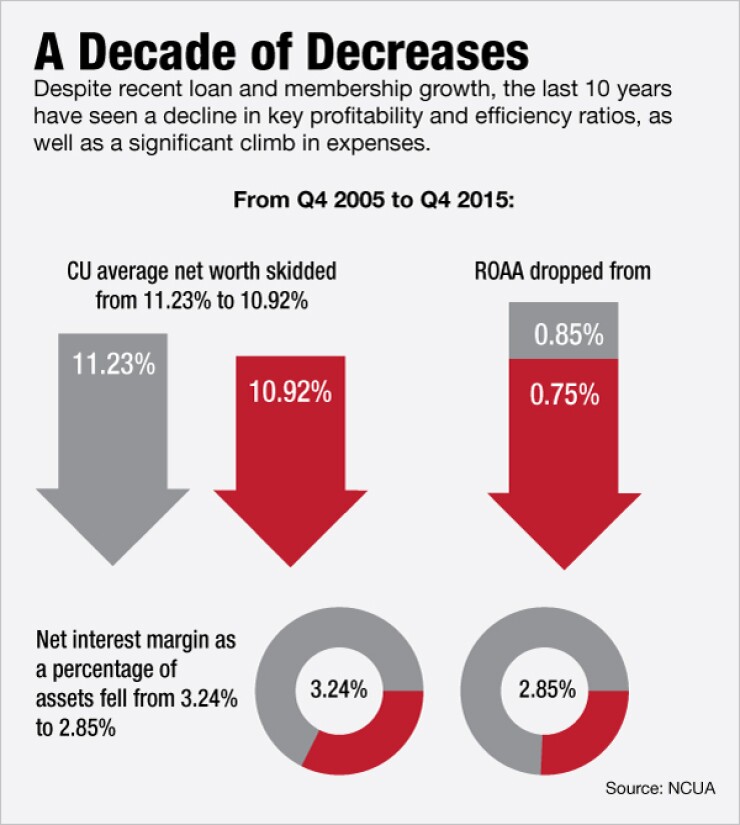

For example, from the fourth quarter of 2005 to the fourth quarter 2015 (a period that included the Great Recession), the average net worth of a credit union — that is, net worth as a percentage of assets — skidded from 11.23% to 10.92%.

Similarly, over that same period, return on average assets dropped from 0.85% to 0.75%, while net interest margin as a percentage of assets also fell from 3.24% to 2.85%.

Meanwhile, Costs Keep Cimbing.

During that same decade, total expenses at credit unions surged from $35.6 billion to $46.3 billion. Within those figures, non-interest expenses (or fixed operating costs) soared from $21.5 billion to $36.2 billion; labor expenses almost doubled from $10.7 billion to $18.4 billion; while office expenses increased from $5.9 billion to $9.3 billion.

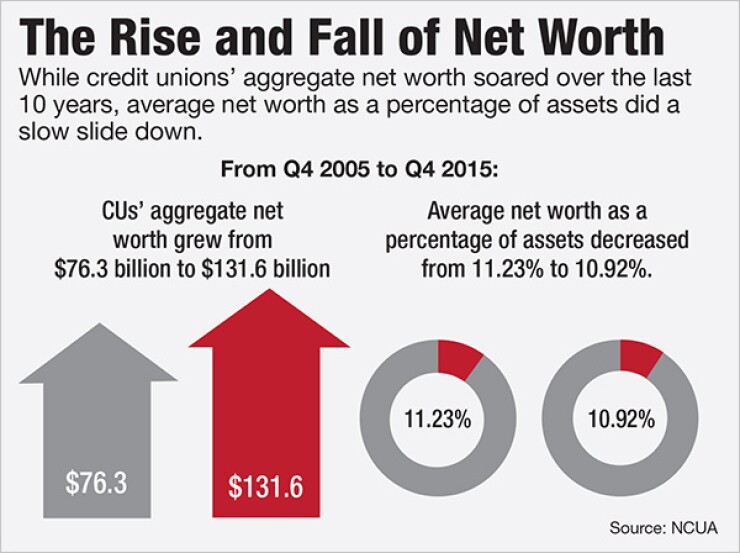

Finally, while CUs' aggregate net worth leapt from $76.3 billion to $131.6 billion over the decade between the ends of 2005 and 2015; their average net worth as a percentage of assets slid from 11.23% to 10.92%.

Meanwhile, operating costs — especially those related to compliance — are also cutting into the bottom lines of credit unions.

Eric Weikart, managing director of performance solutions at consulting firm Cornerstone Advisors, estimates that costs related to compliance around the Bank Secrecy Act, vendor management, mortgages and overall enterprise risk management have doubled in just the last five years. Credit union executives are very aware of these developments and are seeking ways to resolve them, he said.

Balancing Costs vs. Service

"Credit unions are finding increased compressions of their margins and complying with new regulations continues to drive up costs and resource usage," said Rick Blood, SVP-member services at Firefly Federal CU, a $1.1 billion institution in Burnsville, Minn.

Jackie Henderson, VP of human resources at $741 million Rivermark Community CU in Beaverton, Ore., said it is "definitely harder" to generate positive net income, and rising compliance costs is just one of many factors.

"Another is the [interest] rate environment we are in today," Henderson said. "Credit unions are competing with one another for [a] share of wallet, and members, especially [those from] Gen-Y, want to be able to transact anywhere—not just in a branch, but rather from their phones, tablets, and computers. That means a costly investment in technology."

Keith Troup, EVP and COO at Y-12 FCU, a $970 million institution based in Oak Ridge, Tenn., said CUs are also "under tremendous pressure" from competitors with lower cost structures. "Most of these are 'non-traditional' competitors who, in many cases, do not have [to bear] the cost of [running a] brick-and-mortar [operation]."

But the dilemma that confounds many CUs remains: how much do you cut before services to members are compromised?

Dennis Dollar, an Alabama-based credit union consultant, explained that credit unions are always under business pressure and supervisory pressure to improve their bottom lines because they can only build capital through retained earnings — therefore, improved earnings will always be under pressure.

"But it must be counter-balanced with their growing member-owner demands for more technology, enhanced services, greater convenience and better pricing," he added. "The key to a successful credit union is the ability to balance the increasing pressure to build capital through improved earnings with the increasing pressure of member demands for more convenient and better-priced services. Both are very real pressures and both must be accommodated."

Cost-cutting is clearly becoming an increasingly important theme for credit union boards as competitive pressures and cost burdens increase.

"Our board of directors are very interested in growth, and focused on ensuring that we are managing the credit union efficiently so that we can provide a better return to our members," stated Henderson. "The more waste we can identify in our processes creates efficiencies that allow us to do that. Our credit union is in a rapid growth mode, so it becomes even more critical for us to be responsible with spending."

The key is to determine how far a credit union can go with cutting costs before such actions have a negative impact on the membership.

"You must have a strong set of metrics in place to ensure that your members' needs and/or satisfaction are not being compromised at the expense of cost cutting measures," Henderson stated. "It is possible to cut too deep, which is why having metrics in place is so critical."

Blood noted that as credit unions find themselves looking for ways to either increase revenues or decrease expenses, "we would always prefer to offer new value [-added] products and services to our membership [rather] than… raise fees or take steps to reduce costs that may negatively impact the overall member experience."

Troup noted that Y-12 FCU has been very focused on cost-cutting measures over the past few years. One way to shave expenses, he suggested, is renegotiating contracts with vendors and third-parties.

"Many credit unions will accept the first price they are given from a vendor — [but] this should never be the case," he said. "Credit unions should not be afraid to ask for 25%-30% less than the price they were [initially] quoted. You [would] be surprised how many times vendors will accept the revised terms."

Labor Costs and Layoffs

Colin Anderson, president & CEO of $1.8 billion ORNL Federal Credit Union in Oak Ridge, Tenn., said his organization seeks to keep costs under control by periodically reviewing expenses and noting where efficiencies are maximized. "We use a profitability reporting system that helps us identify strengths and weaknesses in our structure," he said. "Based on these ad hoc reviews, we determine appropriate pricing strategies and staffing levels."

Anderson posits that credit unions can prevent (or at least minimize the likelihood) of layoffs and branch closings by ascertaining beforehand how much capacity the company actually has. "That way, we don't get ourselves unnecessarily extended," he added.

Anderson pointed out that since he has been at the helm of ORNL FCU, the company has not laid off any worker.

Troup conceded, however, that at credit unions, staffing usually represents the biggest expense — and sometimes, cutting jobs is a painful, but necessary, step.

"I would suggest [credit unions] not automatically [replace] a [position], when it is vacated due to staff retirement or resignation," he said. Instead, CU executives should ask themselves: "Is there a better way to do things where the role would not need to be replaced?"

Henderson noted that with the unemployment rate now at its lowest levels in many years, employers are forced to pay above-market rates coupled with other incentives to attract and retain employees.

Anderson of ORNL noted that his credit union has to pay above-market wages to attract some workers since unemployment levels are quite low in the Oak Ridge area and competition is strong especially among the Oak Ridge National Laboratory and other local financial institutions.

"We have a fairly stable labor market here and the government-related jobs produce a kind of an anti-recessionary climate. Thus, we have to sometimes compete with the Laboratory and other businesses for workers — so we offer higher-than-average salaries. But that's a cost of doing business here."

But with regard to layoffs, Anderson delineated the key differences between the dramatically different cultures found in banks vs. credit unions. "Banks are very committed to maintaining efficiency and net income," he said. "And if they have one bad quarter when they fail to meet performance targets, job cuts almost always ensue. But credit unions aren't like that — we, too, are concerned with efficiency, but, generally we are more concerned with returning value to the membership, so we can be patient about costs."

Indeed, credit unions do not fire workers at anywhere near the rate nor magnitude found in banks. "Banks are larger and have less of a personal interest in any one location or employee, but the difference is also one of our ownership structure," explained Julie B. Linch, SVP-retail delivery at Directions Credit Union, a $663 million institution based in Toledo, Ohio. "The members of a credit union own it — they like seeing familiar faces in the lobby and take a more personal interest in the staff and branch locations. Bank customers are used to not having a say in what happens — the relationship is always less personal.

Henderson at Rivermark also pointed out that layoffs are less frequent at credit unions than at banks because of their differing staffing practices. "In the credit union industry, we typically operate lean [anyway], so we don't over-staff," she indicated. "That way, if loans slow down or the housing market does (such as what happened during the recession), we don't have an excess amount of overhead that needs to be reduced."

Cut Some Branches?

Another cost-savings technique is closing unprofitable branches.

"As our members demand more and more ways to conduct transactions electronically through mobile devices, the need for branching diminishes somewhat," Henderson explained. "Closing under-utilized branches, especially larger branches with big-ticket lease prices and large headcounts can [result in] a big cost savings to the credit union and… creates an efficiency gain. [This can] be returned to the members in the way of increased convenience and access, lower rates, and lower fees."

Indeed, Anderson indicated that of ORNL's 32 branches, they are currently in the process of closing one office because of under-utilization.

There are pros and cons to this method of cost savings.

"There can be a rather quick savings by closing a branch office," said Linch. "But the ramifications are long term. If you're closing an office where another isn't available you'll lose most of your membership base in that area, whereas if you have other branches nearby it should have a much smaller impact. The actual facility needs to be considered as well — if you're leasing and can get out of the lease, it's relatively easy. But if you own the branch building you still have to maintain it so many of your fixed costs remain until it's sold."