A resurgence of credit unions buying banks has led to a fresh outcry by bank industry lobbyists, who say the activity demonstrates how credit unions are taking advantage of their federal tax exemption in ways Congress never intended.

Banking advocates claim credit unions are increasingly deploying cash generated by the tax exemption to offer prices banks often can’t afford to match. They also say it's bad public policy, arguing that such deals add to the federal deficit because they effectively remove taxpaying banks from federal tax rolls.

While credit unions have been buying banks for years, the trend spiked in 2019, when 16 credit union acquisitions of banks were announced, up from nine in 2018. The count tumbled in 2020 amid the coronavirus pandemic, but mergers and acquisitions bounced back in 2021 — prompting bankers to press the issue with lawmakers.

“We’ve been banging this drum on Capitol Hill,” said Aaron Stetter, executive vice president for policy and political operations at the Independent Community Bankers of America.

“At the end of April, all our bankers had virtual meetings with their members of Congress. One of the top issues was to request hearings" on the tax exemption, Stetter said. “We had a lot of good discussions, and a lot of the talks were fueled by these acquisitions.”

The American Bankers Association, too, wants lawmakers to review the issue.

“Our continued request is for Congress to do the work it needs to do to provide proper oversight and to see if the tax exemption is still warranted,” said James Ballentine, the ABA’s group executive vice president for congressional relations and public affairs.

So far, the pleas have been largely ignored.

Credit union trade groups contend that the tax exemption yields tangible benefits for members — who now number nearly 126 million. Meanwhile, Congress appears no closer to scheduling hearings on the 84-year-old tax exemption than it was a year ago, or the year before that.

Rodney Showmar, CEO of the $1.6 billion-asset Arkansas Federal Credit Union in Jacksonville, dismissed bankers' claims that credit unions pose a competitive threat, noting that the credit union industry’s $1.95 trillion in cumulative assets are dwarfed by banks’ total of $22.6 trillion.

"For the life of me I still can’t comprehend why the banks spend so much time, effort, energy, and money fighting to eliminate a competitor that has a less than 10% market share in their industry," Showmar said. "If the entire credit union industry was eliminated overnight, most banks would not even notice, and the ones that did wouldn’t see enough of a benefit to justify all the posturing.”

Viewed from a different angle, bankers’ cause for concern isn’t as easy to dismiss. Credit unions are growing at a more rapid clip, with assets increasing by an average of 9% since 2016, compared with 7% a year for banks.

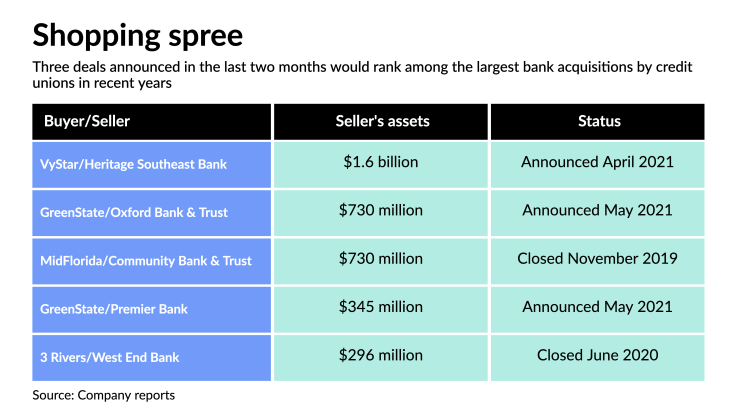

Then, there are the deals.

The most notable transaction, one that angered community bankers, came in April, when the $10.7 billion-asset

The price VyStar agreed to pay amounts to 184% of Heritage South’s tangible book value — significantly higher than the 156% average for 2021 bank deals, according to Janney Montgomery Scott analyst Brian Martin.

Other notable deals include Wings Financial Credit Union’s agreement to buy one of Minnesota’s few remaining depositor-owned banks, Brainerd Savings & Loan in Brainerd — a deal that quickly drew

Last month, the $7.5 billion-asset Green State Credit Union in North Liberty, Iowa, announced

It’s clear bankers view the latest spate of credit union acquisitions as a serious threat.

Lloyd DeVaux, CEO of the $522 million-asset Sunstate Bank in Miami, said his market is already home “to just about every bank in the world.”

Nevertheless, Miami nearly lost one of those banks to a credit union buyer last year, when the $13.5 billion-asset Suncoast Credit Union in Tampa, Florida, agreed to acquire the $904 million-asset Apollo Bank in Miami. They agreed in May 2020 to call off the deal because of the pandemic.

Buying Apollo would have given Suncoast “a big presence in the market,” DeVaux said. It's just a matter of time before a credit union sets its sights on another local bank, he said.

“We’re used to competition, but then you’d have someone who could go significantly lower in price,” DeVaux said. “If I have to charge 6% on a loan to pay 1.5% of that in taxes, credit unions can charge 4.5% … there’s always price elasticity. If you can charge less, you’re going to take more of the business.”

Since VyStar’s announcement, the industry’s leading trade groups, the ABA and the ICBA, have

Both continue to press the case, expressing hope the acquisition trend might prompt Congress to take a fresh look at the tax exemption. “I’m sure Congress didn’t bestow a general exemption on the credit union industry so they could target tax-paying banks,” Stetter said.

The size of the credit union-bank deals may draw fresh scrutiny, said Ballentine. “At some point, we believe Congress will begin taking a serious look at this.”

The last time either house of Congress examined credit unions’ tax exemption was in November 2005, when then-House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Bill Thomas, R-Calif., held a hearing on the issue To date, no lawmakers in either house of Congress have indicated any willingness to schedule new hearings.

A spokesperson for the Ways and Means Committee had not responded to an inquiry from American Banker by deadline.

Michael Bell, an attorney who co-chairs the financial institutions practice at Honigman, has advised many credit unions on bank acquisiitions.

Bell characterized bankers' complaints about acquisitions by credit unions as overheated, noting that credit union-banks deals fail more than they succeed. There are roughly seven rejections for every winning credit union bid, according to Bell.

“The market is free, and it cuts both ways,” he said.

But credit unions remain willing to challenge the odds. Showmar has made no secret of his desire to buy a bank, but he said his credit union has a well-defined scope for M&A targets. Though there have been several candidates, ultimately none measured up enough to move forward.

Still, “with the increase in M&A activity that has already occurred, I anticipate more opportunities to come our way as the year progresses,” Showmar said. "Maybe one will be a good fit."

Talk like that gets under the skin of banker groups.

Credit unions are using tax and regulatory benefits available to their industry “as an opportunity to purchase banks at [prices] no bank would be able to pay,” Ballentine said. “If you and I are making the same amount of money and I am not paying taxes, then you and I are not making the same amount of money.”

The scale of the deals is just one factor. The trend should also be examined from a public policy standpoint, according to Richard Garabedian, an attorney who has worked on cross-industry mergers.

“Should we permit a tax-exempt entity that is not a charitable operation to acquire a tax-paying entity? A Community Reinvestment Act-observant institution is also lost. These transactions make perfect sense for the credit union but are questionable from a fiscal policy standpoint," Garabedian said.

Problem is, “there doesn’t seem to be any mechanism to stop it,” Garabedian added.

If you and I are making the same amount of money and I am not paying taxes, then you and I are not making the same amount of money.

DeVaux, likewise, holds out little hope for timely action by lawmakers.

“Members of Congress … would prefer to just leave well enough alone, don’t rock the boat,” DeVaux said. “There’s very little support for doing anything other than that right now.”

At the same time, DeVaux says bankers have marshaled a strong case against credit-union bank deals, especially given the rising tide of government debt.

“When you’re scrambling to pay for a $6 trillion budget, it seems like that would add fuel to the fire to get rid of some costly tax loopholes … it makes so much sense, but nobody wants to take it on,” DeVaux said.

Nobody should, said Geoff Bacino, a credit union consultant who served on the boards of the National Credit Union Administration and Federal Housing Finance Agency.

“These were all business decisions. No one was saying, 'You have to sell to a credit union,’ ” Bacino said. In some of the recent credit union acquisitions, other banks looked at the selling bank but opted not to make an offer, he said.

Banks blame a host of ills on the tax exemption, “but at some point, you’d think they’d see that argument is not going anywhere and say, let'ss come up with a new plan,” Bacino said.

Keith Leggett, a retired ABA economist who continues to follow bank-credit union issues, noted the few lawmakers who have called for a closer look at the tax exemption did so at the tail end of their careers, when they had little opportunity to mount a sustained effort.

Thomas announced his retirement in March 2006, four months after calling the oversight hearing into the tax exemption. Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, released a letter that suggested the credit union industry may have outgrown its favorable tax treatment in January 2018, less than a month after announcing he would not seek re-election.

The ABA and the ICBA were right to make the case against credit union bank acquisitions, labeling them bad public policy, “but I don’t think anything is going to come of it,” Leggett said.

Banks and the nonprofit Tax Foundation claim

While the pandemic put the battling between banks and credit unions on ice throughout most of 2020, the two industries spent years at loggerheads before that. ABA and ICBA launched major lawsuits against credit unions’ federal regulator, the National Credit Union Administration, only to come up empty.

In 2016, the ICBA filed suit to block a revised member business lending rule the trade group claimed weakened congressionally imposed limitations on credit unions’ commercial lending authority. That challenge was thrown out the following year.

The ABA sued in 2017 over another revised regulation that it claimed watered down limits on credit unions’ fields of membership. After an early success at the district court level, where a judge partially invalidated the contested regulation, the ABA’s challenge was tossed on appeal.

Dan Berger, the president and CEO of the National Association of Federally-Insured Credit Unions, predicts that future challenges will lead to the same results.

According to Berger, lawmakers understand communities benefit when a bank’s management team, board of directors and shareholders opt to sell the institution to a credit union.

“These mergers often mean employees retain jobs and branches remain open,” Berger said. “The bankers that oppose these free-market transactions would rather have the selling bank’s branches, lending capacity and economic benefits abruptly exit the community than be serviced by a credit union.”

Bank groups, however, plan to continue pleading their case to lawmakers.

“Frankly, the Congress is shirking its duty by not having these hearings,” Stetter said. “The committees of jurisdiction need to take a strong look at this. We’ll keep hammering the point home.”