Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

As the financial crisis was close to its climax in late 2009, a group of highly experienced bankers gathered in a private room at Midtown Manhattan's 21 Club one afternoon to make a pitch to some of the country's most successful hedge fund managers. Veterans of Bank of America and Wachovia, the bankers said they were looking for several hundred million dollars to set up an institution that would buy failed banks in the South, profiting from the abundant government support available for such deals at the time.

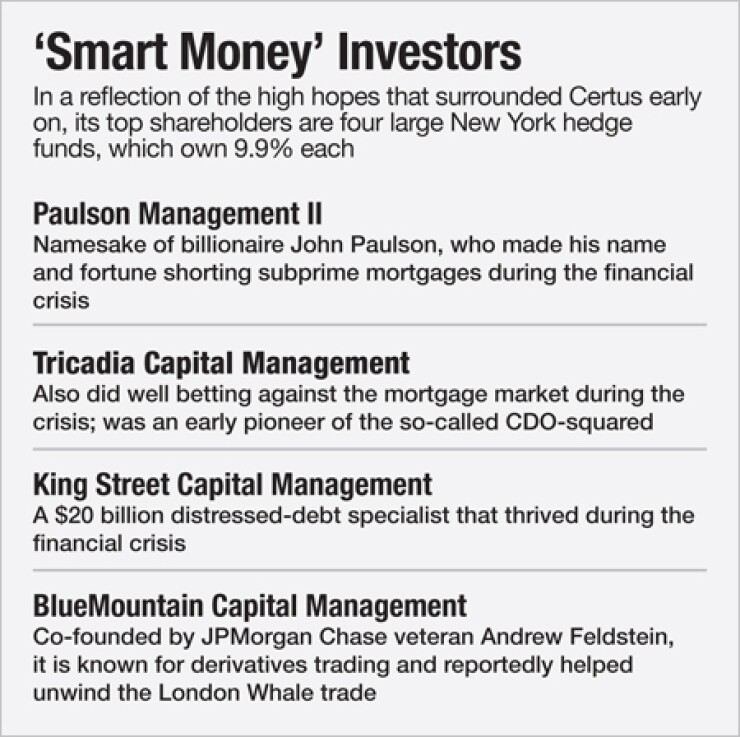

The sales presentation to a standing-room-only crowd of at least 60 was highly polished, according to a person who attended. It also proved a winner. CertusBank, the company the four bankers went on to found, garnered a commitment of half a billion dollars from what one investor called "the smartest of the smart money." Among its members: the hedge fund billionaire John Paulson and Tricadia Capital Management, a pioneer of financial instruments like the CDO-squared.

Lately, however, meetings among investors in the $1.7 billion-asset Certus have taken on a decidedly grimmer tone. On March 11, a group of investors held an emergency conference call to discuss ousting the board over what some regard as gross mismanagement by senior executives and possibly worse.

Among the concerns: nearly $10 million paid to a consulting firm owned by Certus' top officers; $146,000 for three months of work by an executive's son fresh out of college; $2.5 million for three executive apartments and high-end upgrades; $347,000 for private plane trips; $131,000 for Carolina Panthers games; several hundred thousand dollars for sponsorships and charitable gifts; and more than $500,000 for American Express bills. That's according to documents reviewed by American Banker and two people with direct knowledge of the bank's operations.

Certus also opened a new headquarters in one of Greenville, S.C.'s most expensive buildings. Amenities include a nearly $1 million art collection, a theater and a 13-foot touch-screen "media wall" that, the bank says, is the tallest in the United States. Another unusual feature: 300,000 pennies that a Certus official had affixed to the ceiling of an office suite, according to two people who have visited the headquarters.

All the spending has resulted in an explosion in noninterest expenses at Certus that contributed to combined pretax losses of more than $115 million in 2012 and 2013.

"Over the past two years, more than $100 million of equity capital has been erased in the most baseless and irresponsible way by spending exorbitantly on personal excess masked as corporate expense," wrote Benjamin Weinger, managing partner of 3-Sigma Value Financial Opportunities, a New York hedge fund, in a March 5 letter to fellow Certus investors that was obtained by American Banker. "This can go on no longer."

Investors will have the chance to vote on a new slate of directors at Certus' June annual meeting. Several have also hired law firms to explore ways to rein in Certus' management, according to people familiar with their activities.

Whatever the outcome, Certus' fast rise and recent troubles pose prickly questions for all parties involved. They include: whether political influence helped Certus prevail among the dozens of groups vying for access to failed-bank deals; whether its investors let the prospect of government largesse and outsized returns entice them into forgoing important controls; whether Certus' troubles support the view that private equity and hedge funds are ill-suited to owning banks; and whether its managers have spent improperly.

Certus certainly has company among crisis-era startups that have disappointed backers, who came into the deals expecting more bank failures than ultimately occurred. Companies like NBH Holdings, Bond Street Holdings and Capital Bank Financial Corp. have all had a

In Certus' case, there is also the chance that regulators will step in before the bank or its investors take action; the bank's losses recently pushed its tangible common equity ratio, a key measure of its solvency, below the level required by the company's federal charter.

Along with its losses, Certus has suffered an exodus of key employees. More than two dozen senior staffers have left since December 2012, including two chief financial officers, the latter of whom resigned in late February. That post remains vacant. Certus is also working with its fourth investment bank in the past two years.

"The board of directors of CertusHoldings, Inc. takes seriously the concerns expressed [by company investors] and, accordingly, the Board has unanimously approved the formation of a committee of independent non-executive directors to evaluate and respond" to questions about its operations, Certus said in a written response to queries from American Banker.

"We would urge all interested parties not to rush to judgment, or to form any conclusions until all facts and relevant circumstances are determined," the statement says. "We anticipate that all concerned will recognize the importance of an independent review being conducted professionally and objectively such that reasoned conclusions, established in facts, can be expeditiously reached, guiding our response. " Certus declined through Edelman, a public relations firm, to respond to specific concerns raised about its operations.

"Dream Team"

The disarray at Certus represents a dramatic fall for a management group that, less than five years ago, impressed some of the world's savviest investors.

Investment bank FBR Capital Markets arranged the 21 Club gathering and some 30 others as part of a road show aimed at raising $500 million for Certus. FBR managing director David Toepel called the four bankers who would run the fledgling institution the "Dream Team" of banking, in reference to the 1992 U.S. Olympic gold medal basketball team, according to a person who attended the meeting. Toepel doesn't recall ever referring to the group as the "Dream Team," he says.

The plan was for Certus to form a company that would buy failed banks along a corridor of Interstate 85 running from North Carolina through Georgia, a region

Leading Certus was Milton Jones, who'd recently left a position as president of Bank of America's Georgia operations, where he oversaw more than 150 branches and thousands of employees. In 32 years with B of A, Jones had held senior roles in finance and risk management and had sat on its management committee.

An Atlanta native, Jones was also a mover and shaker in the city's business and philanthropic communities, sitting on the boards of several nonprofits, including the Atlanta Business League, United Negro College Fund and Metro Atlanta YMCA.

Joining Jones were Charles Williams and Walter Davis, close friends and neighbors in Charlotte, N.C. Each had recently left a high-level position at a large bank: Williams at B of A, where he was its investment bank's chief administrative officer; and Davis at Wachovia, where he'd headed the retail credit unit.

A fourth member of the group was Angela Webb, whom Davis and Williams had persuaded to leave her job as head of human resources for Wachovia's mortgage unit.

At the 21 Club event, the group told investors that the plan was for Jones to head the bank as its Atlanta-based chairman and chief executive. Williams would serve as chief operating officer and Davis as chief credit officer; each would also hold the title of vice chairman. Webb would be chief administrative officer.

For Davis and Williams, the new company would be the realization of a long-held ambition. The two men had been drawn together by religious faith and an ambition to build a bank that they'd long discussed over Saturday breakfasts at the Original Pancake House in Charlotte, Williams told EnVision Life, a North Carolina talk show, in 2010.

"For eight years, we had been talking about doing something special. It became almost like a ritual," he said at the time.

To potential investors, the group was presented as offering experience, talent and one other key quality that could help distinguish it from the many rivals with similar business plans at the timethe political connections to give it an edge in obtaining the bank charter necessary to become a federally insured institution and acquire failed banks, according to people present at investor meetings.

Even the bank's nameLatin for "certain"was chosen because of its founders' desire to "bring certainty back to banking," according to a press release and interviews the founders conducted with the local business press around the time the bank was created.

Golden Charters

Obtaining a charter and investing in busted banks was a relatively new strategy in the wake of the financial crisis. When banks fail, regulators typically sell the remains to healthy institutions to limit the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.'s losses. However, the glut of crisis-era bank failures, combined with heavy industry losses, resulted in a shortage of potential buyers.

Regulators responded by allowing outsiders to bid for failed banks. To qualify, investors had to commit capital and assemble experienced management teams and boards. They were then allowed to apply with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency for a so-called shelf charter, which, if approved, would allow them to take part in FDIC failed-bank auctions. If they won an auction, their shelf charter was converted into an active charter at the time they took over their troubled target institution.

Two deals in early 2009 worked out very well for investors and helped draw a horde of suitors to failed-bank dealsIndyMac's sale to a group led by John Paulson and George Soros and BankUnited's sale to a group that included former North Fork boss John Kanas and billionaire Wilbur Ross.

Investors were also drawn to such deals by the view that they posed little risk, thanks to the FDIC's willingness at the time to guarantee buyers against many losses from acquired banks.

By mid-2009, groups backed by some of the highest-profile investors in the country, and managed by experienced bankers and former regulators, were clamoring for access to the failed-bank market. Demand for these deals remained high even after the FDIC

The biggest barrier to entry for these deals was obtaining a federal charter. Because of the number of suitors, bank regulators could be highly selective and granted a total of just five national shelf charters in 2009 and 2010, according to the OCC.

It was in the contest for a charter that some of Certus' backers believed their management team's experience and political connections could provide an edge. These connections were part of the group's sales pitch, according to people who were present at investor meetings.

It's unclear just how much political clout Certus really had, but its founders clearly made it a priority to nurture Washington ties.

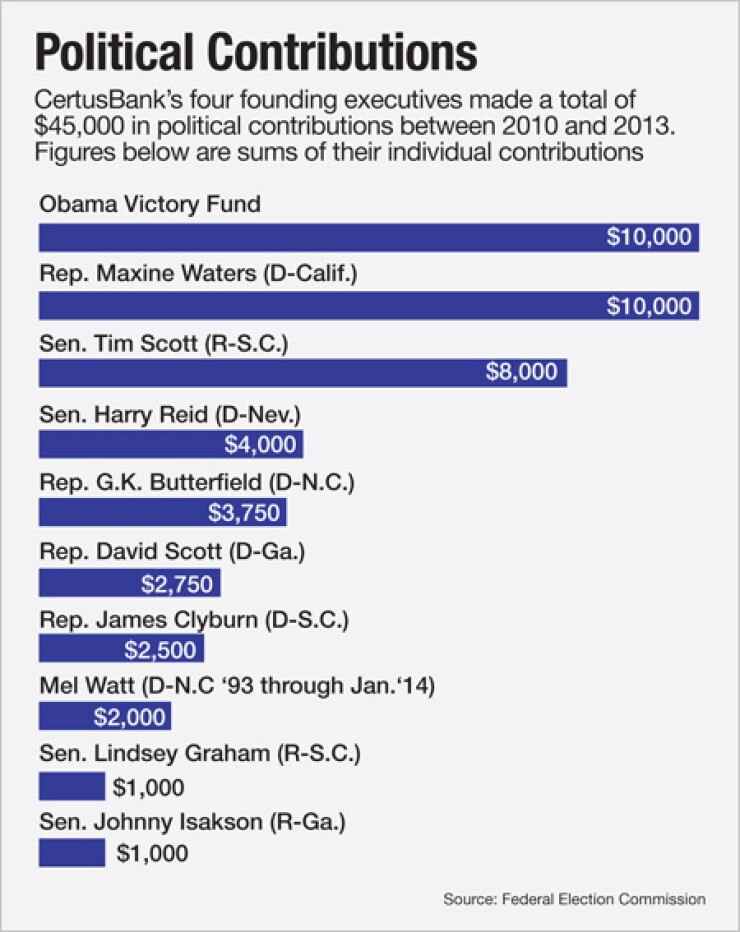

The four founders made a total of $45,000 in political contributions between 2010 and 2013, including $10,000 to the Obama Victory Fund in 2012 and $10,000 for the 2012 reelection campaign of Rep. Maxine Waters, lead Democrat on the House Financial Services Committee. (See table, "Political Contributions.")

Executives also surrounded themselves with politically connected colleagues and advisors.

Certus' board member J. Veronica Biggins was President Bill Clinton's personnel director in charge of hiring political appointees. The bank's political ties extend to Integrated Capital Strategies, the distressed-debt consulting firm set up to work out bad loans for Certus. ICS managing director L. Maurice Daniel is a former chief of staff to representative Rep. Bobby Rush (D.-Ill.) and was National Political Director for Vice President Al Gore.

Certus also hired well-connected advisors. FBR's investment banking head Ken Slosser spent ten years with the Office of Thrift Supervision, which was folded into the OCC in 2011. Former FBR banker Kevin Stein, who worked with the Certus group before leaving the investment bank in 2011, is a former official in the FDIC division that resolves failed banks. Joseph Jiampietro worked as a senior advisor to then-FDIC chairman Sheila Bair for two years through 2011 before moving to Goldman Sachs, where Certus became his client the following year.

Company executives also reached out to key regulators while they were seeking bank status. In January 2010, Jones, Davis, Williams and FBR's Stein met with Bair, according to her schedule.

Yet it's not clear the meeting was necessary or even helpful. Approval for the bank's charter came through the OCC, not the FDIC, though the two agencies' staff work together to vet prospective new banks. It was FDIC policy to accommodate requests for outreach meetings with Bair, according to Andrew Gray, the agency's spokesman.

Certus execs also held at least one meeting with members of Congress while seeking regulatory approval to become a bank.

The OCC ultimately granted the Certus group preliminary approval for a national charter in October 2010. Citing agency policy, it declined to comment on matters related to Certus, as it remains an open and operating institution.

Meanwhile, Certus was making progress raising money. In the six months after its December 2009 application to become a bank, it achieved its goal of lining up $500 million in financial commitments from around 25 investors. Demand was so strong that FBR canceled several road show stops.

Four funds came in as lead investors, each with 9.9% of the stock. They include: Paulson Management II, Tricadia Capital Management, BlueMountain Capital Management and King Street Capital Management (see table).

King Street declined to comment for this article. The other three lead investors did not respond to requests for comment.

For Certus' largest investors, a bet on the bank was to an unusually large degree a bet on management. Regulators' strict guidelines required failed-bank investors to lock up capital for a minimum of three years. In Certus' case, voting stock held by each of the four lead investment groups was capped at 9.9%, and they also agreed not to act in concert to influence the bank's management. Other investors were limited to 4.9% stakes.

Investors hoped to protect their interests via a requirement that Certus would register its shares for a public offering within six months of its first failed-bank acquisition. In addition, Howard Bluver, a former federal bank regulator and risk management expert, was appointed to Certus' board to represent outside investors.

For Jones, Davis, Williams and Webb, the payoff was supposed to come via sweat equity. None put up the money for more than a fraction of a percent of Certus' holding company. However, stock incentives could have pushed the four executives' collective ownership stake to about 7% in the event of a successful IPO, according to a regulatory filing. In addition, salaries were set at $340,000 for Jones and slightly less for the three other executives.

Aiming for $5 Billion

Certus achieved full bank status on January 21, 2011 when it acquired South Carolina's failing CommunitySouth Bank & Trust from the FDIC. CommunitySouth, which was six years old, had run into trouble due to heavy exposure to mortgages and had roughly $450 million in assets at the time Certus acquired it. The transaction rendered Certus one of only two new banks in 2011.

CommunitySouth was part of Certus' "aggressive" strategy to become a $5 billion-asset bank within two years, chief credit officer Walter Davis told the GSA Business Journal, a Greenville paper, shortly after closing the deal.

"Our investors want us to spend the $500 million [committed] quickly and come back for more," he said.

The company appeared well on its way to that goal when, four months later, it

All three acquisitions were so-called negative bid deals, in which the FDIC pays the buyer to take over an institution whose liabilities exceed its assets. In total, Certus received more than $241 million from the FDIC, according to a 2011 KPMG audit. The FDIC also protected Certus against 95% of any future losses on loans acquired in the three deals via a common loss-sharing arrangement, according to one investor's analysis.

The transactions left Certus with more than 30 branches, $1.8 billion in assets and more than half its investors' $500 million commitment still untapped. They also left Certus with a 2011 profit of $61 million, thanks to a more than $110 million accounting gain related to the failed bank deals, according to its audit.

"The first three assisted deals were very strong and set them up very well for the future," said a person involved in the company's creation, who asked not to be named.

Brick Wall

That bright future never arrived. After the first three deals, the FDIC informed Certus that it would not be considered for further acquisitions until it built up its infrastructure and invested in turning the troubled banks it had bought into a viable franchise.

Such cooling-off periods are common but also test bankers' ability to switch from acquisitions to the grinding task of turning around troubled banks. Early in this process, in February 2012, the bank carried out a reorganization that reduced the role of Milton Jones, the Certus executive with the most experience managing a retail network. Jones relinquished the president and CEO titles and became executive chairman. Davis and Williams became co-CEOs, and Webb became president. The reorganization frustrated some investors, who had been sold on Jones' leadership of the bank.

From Certus' creation, its founders were explicit that they planned to hand off a significant portion of the integration work to ICSthe consultancy Williams and Davis founded in 2009 and in which Jones and Webb are managing partners. Regulators and investors discussed the setup with Certus' founders before the bank was created and ultimately agreed that transactions between the two would be overseen by Certus' board.

The relationship "has been reviewed by our regulators and auditors without issue," Milton Jones wrote in a letter to shareholders this January.

In contrast, some Certus investors now appear to have big issues with the Certus-ICS arrangement. Certus paid ICS $9.7 million in the three years through 2012, with monthly invoices running as high as $700,000, according to KPMG's audits and documents obtained by American Banker. ICS earned net income of nearly $1.9 million in 2011 and 2012, and paid out more than $1.5 million in what was described as distributions to members, repayments of member capital and principal payments on notes, according to an audit by the North Carolina accounting firm GreerWalker.

Davis and Williams acted in their capacities as Certus officers to approve some payments by the bank to ICS, despite the fact that they founded and owned the consulting firm, according to documents obtained by American Banker.

Another concern: Certus was billed $194 an hour by ICS, or a total of nearly $146,000, for the services of Bryan Williams between June and August of 2011. Bryan Williams is the son of Certus founder Charles Williams and had graduated from North Carolina State University the previous year.

The rate Certus was charged for his services was near the middle of ICS' range, despite the fact that his only previous work experience was as an assistant high school basketball coach, according to Williams' LinkedIn profile. His rate was reduced to $75 an hour in September 2011, according to internal ICS documents. Williams is currently employed by Certus itself as a "liquidity management/portfolio analyst," according to LinkedIn. Bryan Williams did not respond to requests for comment.

As scrutiny of Certus' relationship with ICS has grown, the bank reduced its billings and terminated its contract entirely at the end of 2013, according to company documents.

Two other transactions have raised concerns as well.

In February 2013, Certus extended two loans for a total of $2 million to 100 Black Men of Atlanta, a nonprofit that promotes education and mentoring of young men, according to two people familiar with the bank's internal operations.

Both loans are currently listed as "classified," meaning Certus believes the borrower is likely to default, these people said. The bank spent another $9,000 supporting the group's 2012 Atlanta Football Classic, according to Certus documents. Milton Jones, Certus founder and executive chairman, also chaired the nonprofit between 2009 and 2011 and now serves as a director.

John Grant, executive director of 100 Black Men of Atlanta, declined to comment.

Another transaction involves the bank's sale to then-chief operating officer Charles Williams of a 2006 Toyota 4Runner at what may have been far less than the market value, according to documents reviewed by American Banker. The title to the vehicle was held by Certus in September 2011.

That month, Walter Davis authorized the sale of the vehicle to Williams, according to the documents. Williams wrote Certus a $300 check with the word "Truck" in the memo on Dec. 11, according to the documents. A vehicle of the same make and with the same VIN number was later offered for sale by a South Carolina used car dealer for $13,488.

Planes, Clubs, Artwork

Certus' spending on costly amenities has emerged as a serious concern among the company's investors, its former employees and others associated with the bank.

In August 2012, the bank bought three apartments in Greenville, S.C., for about $500,000 each, according to tax records. These apartments were used by Davis, Williams and Webb, a former employee says. Certus spent nearly $1 million more in 2012 to improve and decorate the three apartments, according to internal Certus statements of expenses viewed by American Banker and whose accuracy was confirmed by two people familiar with Certus' operations.

Among the nearly $1 million in improvements are a wine cellar, at $11,925; a TV cabinet, at $15,350; and $23,135 for electronics, according to the internal expense statements and the two people familiar with Certus' operations. (

The bank has spent millions more on its headquarters. Located at One North Main in Greenville, it is, at $28 per square foot, among the city's most expensive addresses, according to real estate data firm CoStar.

The headquarters features a C-shaped bar with dozens of mobile tablets and a 13-foot media wall, according to reports in the Greenville press. Management has also installed a theater, fireplaces in executives' offices, marble floors, a steam room and a ceiling covered in 300,000 pennies, according to the two people familiar with Certus' operations.

Certus has spent roughly $1 million more on headquarters art, the employees say. Its expense statements show the company spent $871,000 on its art collection in 2012, with the largest single expense $153,000 for a painting entitled Sixty by Fifty Number III by New York abstract painter Pat Steir.

Certus' entertainment bills include $131,250 for Carolina Panthers games, according to the internal expense statements. Additionally, the letter Weinger sent to Certus shareholders claims the bank spent $173,000 on other sporting events in 2012.

Certus has also run up high travel and vehicle expenses. The company bought three SUVs, for about $60,000 each, in 2012, according to the statements of expenses. Executives regularly charged the company for limousine and car services throughout 2012, the documents show. It paid more than $347,000 in 2012 to the charter aircraft companies AeroCab and Marquis Jet, the records show.

Certus made 34 payments totaling $48,500 to the Commerce Club, an Atlanta social club, in 2012, the documents show. Milton Jones is a Commerce Club board member, according to his bio on Certus' website.

Charitable gifts and sponsorships have been another Certus priority.

Certus has spent well in excess of $1 million on charitable contributions during its short life on a wide range of causes.

It spent $118,750 to help pay for the nonprofit Congressional Black Caucus Political Education and Leadership Institute's 2012 convention, according to internal Certus documents. Maurice Daniel, the former Al Gore aide and ICS managing director, sits on the executive committee of the institute's 21st Century Council, a policy group.

In 2012, Certus pledged $1 million to renovate a portion of the Peace Center for the Performing Arts in Greenville, which was renamed the Certus Loft. It also sponsored the "Certus Broadway Series," which has brought popular musicals, including Phantom of the Opera and Jersey Boys, to the Peace Center.

The bank donated another $175,000 to the Greenville County Museum of Art in October 2012 for the purchase of 19th century stoneware vessels and an arts program called "Certus Saturdays."

Other 2012 contributions include $30,655 to the United Way of Greenville County, $29,575 to the University of South Carolina and $25,200 to the Ronald McDonald House, according to a March 5 letter from hedge fund manager Benjamin Weinger to fellow Certus shareholders.

Cost Problems

Certus'

By then, its high costs were beginning to hit home. Its noninterest expenses more than doubled in 2012 from the previous year to $144 million and it recorded a pretax loss of $33 million, according to its KPMG audit.

Noninterest expenses edged up to $146 million last year when the bank's pretax loss hit $83 million, according to its FDIC call report. In total, Certus' expenses of $1.69 per dollar of revenue were far in excess of the 65 cent average for banks with $1 billion to $10 billion in assets.

According to Certus insiders, the board that was supposed keep management in line has failed at the task, and the resignations of key directors has made matters worse. Howard Bluver, the director tapped to represent investors, stepped down in December 2011 after being named CEO of Suffolk Bancorp in New York. At the end of that month Edward Brown, the former head of Bank of America's investment and commercial bank who had been Certus' lead independent director, also resigned from the board. Calls to Brown, who is now CEO of Hendrick Automotive Group, were not returned.

Along with Jones, Davis and Williams, the board now includes five independent directors, according to Certus' website. Only one of the independents has served in a management position at a bank Veronica Biggins, the former Bill Clinton aide, who spent 20 years at NationsBank before it was acquired by Bank of America. Another director, Robert Brown (no relation to Edward Brown), the founder of a North Carolina public relations firm, served on Wachovia's board.

In a letter to shareholders in January, Certus pledged to reduce total expenses by $25 million by the second quarter of 2014. Its plan calls for cutting staff and branches. Its executives agreed to 20% salary cuts, the letter states. Certus also pledged to offer its investors more access to its financials.

Sandler O'Neill, Certus' current financial advisor, has "encouraged CertusBank to work to improve its profitability and transparency with investors, which management has embraced," says David Franecki, a Sandler spokesman.

Why Certus' typically assertive investors have allowed the bank to reach this stage is an open question. Legal strictures on their influence on management may be one reason. Another possibility: Certus may not be a fight worth waging for funds with billions under management and many other regulatory entanglements to consider.

Whatever the reasons, the IPO once hoped for by everyone involved in Certus looks like a dream that this team is unlikely to deliver.

Correction: The original version of this story stated that Certus spent $5,000 at a footwear retailer. Subsequent information indicates that payment was made to another party. A reference to shoes has also been removed from a section headline in this story.