It will be at least two years before banks are required to upgrade their consumer websites to make them accessible to consumers with visual and hearing disabilities, but many are being advised to take action now or risk being sued.

The Justice Department in 2010 announced plans to develop formal guidelines for how all companies, not just banks, must make websites accessible to the disabled. The guidelines will include steps such as adding audio for blind consumers and text alternatives for deaf consumers. The DOJ is expected to issue the guidelines in 2018.

But the issue has taken on added urgency of late as some banks have faced legal challenges from plaintiffs' lawyers who claim their websites do not comply with the existing Americans with Disabilities Act.

Bank of America, for example, reached an agreement in May with an attorney representing a blind consumer to make online mortgage documents accessible. The bank had previously offered to help disabled consumers by sending an employee to the consumer's house to read documents aloud.

Technically, company websites are required to be compliant with the 26-year-old ADA now, but the guidelines are so murky many firms have opted to wait until the DOJ rules come out to make any meaningful changes.

Many banks are stuck in a gray area, as they're waiting on DOJ's guidelines but don't want to be seen as running afoul of the law, said Hugh Wellons, an attorney with Spilman Thomas & Battle in Roanoke, Va.

"The problem is that even though there are not regulations yet, that doesn't mean you don't have to comply," said Wellons, who advises community banks on corporate and regulatory issues. "The banks' problem is they aren't certain what 'compliance' is."

Banks don't want to spend money now redesigning their websites based on unofficial guidelines, only to learn later that the Justice Department wanted something else fixed, added Jenifer Waller, a senior vice president with the Colorado Bankers Association.

"You could in theory make yourself compliant with [one thing] and then have to become compliant all over again if the DOJ's rules are different," she said.

Still, there could be a cost to waiting.

And at least one bank, Wells Fargo, has already been slapped with a penalty for website noncompliance. Wells reached a $17 million settlement with the Justice Department in May 2011, requiring the bank to remove physical barriers inside its retail branches and mortgage offices, and to make its websites accessible to consumers with visual and hearing disabilities.

The new potential for a battle with trial lawyers has forced some banks to move website ADA compliance ahead of other projects. At least seven Colorado banks have received threatening letters from plaintiff's lawyers. Officials with the Arkansas Bankers Association and the South Carolina Bankers Association have also warned their members about the matter.

Banks aren't alone in having a target on their backs. Plaintiffs' firms have sued companies in the retailing and restaurant industry for website noncompliance. The number of these lawsuits is expected to grow, with banks likely to be a primary target, according to the ADA Title III blog published by the law firm Seyfarth Shaw.

Wellons said a bank that receives the letter should not ignore it.

"The first thing they should do is contact their lawyer and then they need to let their [technology person] know about it," said Wellons.

Fred Green, chief executive of the South Carolina Bankers Association, said he has advised his members to contact his group and their legal counsel. In the meantime, the SCBA is developing follow-up advice on what banks should do.

The Arkansas Bankers Association has warned its members about the issue and is working to form alliances with other industry sectors that have been targeted, according to the group's website. The Colorado Bankers Association has planned a seminar for Dec. 13 to educate members about ADA compliance.

In the meantime, if a bank hasn't been aware of the need to have an ADA-compliant website, they do now and they're figuring out what to do, said Virginia O'Neill, senior counsel at the American Bankers Association.

"Our banks understand that being compliant with the ADA makes good business sense and it's the law," she said.

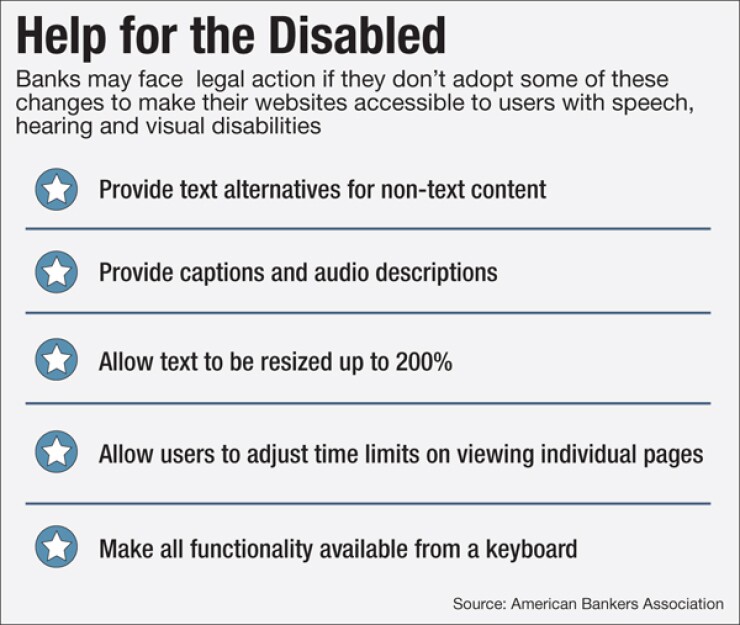

The Justice Department's guidelines may be based on a set of rules promoted by the World Wide Web Consortium's Web Accessibility Initiative, according to the American Bankers Association. Those rules, called Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0, include features such as providing text alternatives for non-text content, offering audio descriptions of site features, allowing text to be resized to a larger font and including captions with online videos.

The Justice Department did not return calls seeking comment.

The cost to make a website compliant with these types of requirements will vary based on the size of the bank and the features offered on its site, said Kathy Wahlbin, chief executive of Interactive Accessibility in Sudbury, Mass. Costs for an initial audit range between $2,500 and $4,500, with follow-up auditing ranging between $15,000 and $30,000. The process of actual website remediation would add to banks' tabs.

Making a website's content accessible to disabled users can be a challenge, said Kirk Reese, the chief technology officer at Docutech.

"It's not a simple task to make website and document content presentable in a manner that a visually impaired person can understand," Reese said.

Online material can't be understood "if the site's not accessible with assistive technology to do screen reading," added Jack McElaney, vice president of sales at Microassist in Austin, Texas, which provides accessibility remediation and training. "It's next-to-impossible or completely impossible to be able to do those types of transactions."