Before they were bankers, they managed taverns in Portland and ran wholesale bakeries in New Jersey.

They were trained as college professors and social workers. Many of them have quickly broken into the top ranks of the banking industry. But their titles often prompt the same question: What is it that you do exactly?

Meet the newest members of the industry's C-suite.

-

How two midsize banks and a marketplace lender are relying on chief culture officers to maintain a lively work environment and preserve their values amid M&A and organic growth.

April 25 -

What does a chief culture officer do? Though this is an uncommon title in banking, it is starting to pop up in more executive suites. Heres why one bank sees the role as an important factor in its effort to excel.

April 25 -

Greg Carmichael, a former IT executive, has been tapped to lead Fifth Third Bancorp, a move showing the growing importance of technology in banks' operations. He'll have to find new ways to grow revenue as he succeeds Kevin Kabat, under whom profitability has sagged recently.

July 8 -

Lateral moves can be a way for women in banking to expand their knowledge base and make themselves more appealing candidates for upper management positions, according to the head of TD Bank's consumer bank Nandita Bakhshi.

November 26

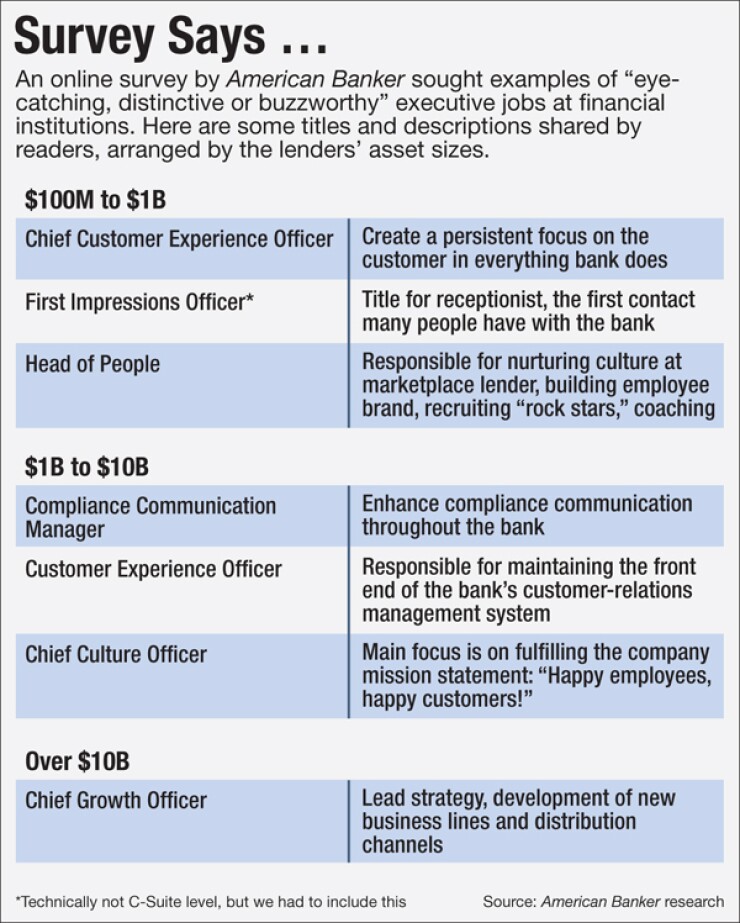

Over the past few years, banks across the country have added a slew of unusual C-level jobs with names that convey an edgy, Silicon Valley-style coolness. Chief innovation officer. Chief customer experience officer. Chief culture officer.

The new breed of free-thinking, entrepreneurial-minded executives oversee a range of functions yet share the common mission of helping banks adapt to a rapidly changing world.

"The next few years will be the most interesting and most challenging times," said Timothy Spence, whose job of chief strategy officer at Fifth Third Bancorp in Cincinnati is one that few competitors have in their executive suites.

"The things that create change are big shifts in the profile of your customer, big shifts in competition, structural changes. Those are the things that change the business. All three are going on at the same time."

At some banks, the flashy titles are all for show, said Carll Wilkinson, a corporate recruiter in Portland, Maine. A chief people officer, for instance, might have the same job as a chief human resources officer.

In many cases, though, the new job titles underscore how banks are reorganizing themselves internally, often with the intent of becoming more digitally savvy, said Rod Taylor, president of the executive search firm Taylor & Co. "The term that was used 10 to 15 years ago is 'business process redesign,' " Taylor said.

Think of it this way: banks are typically structured in silos, with finance, marketing and other departments operating mostly independent of each other. Traditional C-suite roles reflect those divides.

But digital projects require more collaboration. Releasing a new mobile app or analytics program, for instance, requires input from across the bank — from wealth management, commercial banking, legal and so forth.

The new C-suite jobs typically play a role in bringing those departments together — quickly, profitably and with employee morale intact.

"Completely reorganizing the bank to operate across all of the silos is unimaginable," said Gerard du Toit, a partner at Bain & Co. So banks have added new leadership roles to cover the gaps.

The executives who seek out these new jobs have a few traits in common, based on recent interviews.

Many are up-and-coming professionals in their late 30s to mid-40s. Most got their start outside of banking, but say they enjoy working in an industry that is in the midst of disruption.

They hold senior-level roles at sprawling organizations, but many insist they are not the bureaucratic types. In an industry that values caution, they talk passionately and openly about topics ranging from analytics to emojis.

Most importantly, they are eager to make changes — even small ones — to the way banks have traditionally done business.

"That style, that mindset — they're not like those people who are wearing pinstripe suits," Taylor said.

Here is a look at a few of the industry's new roles and nontraditional executives.

From the Department of Big Ideas: Chief Strategy Officer

To understand Spence's role as chief strategy officer, you first need to think about the "big, structural" challenges facing the industry, he said.

Banking "was a really great business for about 30 years, from the early 1980s up until the financial crisis," Spence said.

But improving profitability has been a challenge since then, as low interest rates weigh on revenue, competition for loans intensifies, regulatory expenses rise and technology needs multiply. "We went from a sector that was the darling of investors to a sector that has no growth," Spence said.

The $139 billion-asset Fifth Third — like many regional banks across the country — has posted lackluster results in recent years. In 2015, profits rose 16% from a year earlier, to $1.7 billion, but expenses escalated at a faster pace than revenue.

Spence is in charge of finding new ways to promote growth — through new technology, acquisitions or investments.

The role of chief strategy officer tends to exist in industries that are going through large structural shifts, he said, noting that many retail and media companies also have added them to the C-suite.

Spence joined Fifth Third in September, after a decade at the consulting firm Oliver Wyman. In the months since he arrived, the company has reorganized, shifting several tech-focused groups under his purview. He now oversees about 100 people in areas such as analytics, innovation, mobile banking and M&A.

The reorganization has helped Fifth Third achieve a more disciplined approach to digital projects, according to Spence.

"If you want to make a change, you have to be really deliberate and consistent," he said.

Spence's group is conducting research into the way millennials interact with their finances. It's also implementing a data analytics program for commercial clients.

Spence was not formally trained as a banker — in addition to consulting, he also worked in tech startups. But he said his comfort with uncertainty suits his job.

Liz Dukes Wolverton has been in banking longer than Spence. But she has more in common with him than just a title.

Like Spence, Wolverton sees her role as a change agent and considers her nontraditional background an advantage.

She has been with the $29 billion-asset Synovus Financial in Columbus, Ga., for roughly 14 years — having arrived there with experience that included managing the finances for a concert venue. She became Synovus' first chief strategy officer in 2014.

"I don't think I'm encumbered by some of the historical thinking in how you make money or how you execute strategy in the bank, because I'm a little bit outside of that box," Wolverton said.

Spence, 37, and Wolverton, 42, are the youngest members of the executive suites at their companies, and both report directly to their chief executives (Fifth Third's Greg Carmichael for Spence and Synovus' Kessel Stelling for Wolverton).

Because such roles are unprecedented, Wolverton said she thinks banks are looking to emerging talent to fill them. "They're really aren't a lot of predecessors to pull from," she said.

Each bank that creates a role like this also seems to have its own job description, though she, like Spence, is focused on growth at a company that is trying to evolve beyond its shaky performance in the crisis. Her measures of success include "not just growth, but how you grow, the mix of that growth, how you direct your resources toward that."

"A lot of what we're trying to do is transformational," Wolverton said, adding that the C-level title and the backing of the CEO confer the status necessary to achieve such big changes.

From the Department of High Tech: Chief Innovation, Digital and Data Officers

Not all of the industry's fancy-sounding new jobs are in the executive suite.

Over the past few years, big banks in particular have placed them a few rungs down the executive ladder.

Wells Fargo, for instance, recently added a chief data officer and head of innovation. Both report to the bank's chief administrative officer, not to the CEO.

Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America have added similar roles outside of the executive suite.

Offering a prestigious title is one of the ways that big companies recruit ambitious, top-performing employees, according to Taylor, the executive recruiter from Atlanta.

"It's the appearance of seniority" that counts, Taylor said.

For younger employees, in particular, a fancy title can provide an early career boost, he added.

Charles Thomas (right, in the photo above) joined Wells Fargo two years ago in the newly created position of chief data officer. He previously served in the same role at USAA, the $71 billion-asset savings bank in San Antonio.

Thomas, 45, oversees about 500 employees across the globe. To describe his role at the San Francisco-based company, he prefers to use football analogies.

He plays "offense," using analytics to help the company to sell products. He plays "defense," providing accurate data to regulators and the public. And he plays "special teams," using data to help executives across the company make better decisions.

"We are a true enterprise function," Thomas said, noting that his group works across departments.

Thomas holds a Ph.D. in sociology from Yale, and originally set out to be a college professor. After working as an adjunct, though, he decided that career path did not suit him. "That was horribly misguided," he added.

But Thomas found his calling in financial services, quickly moving up the ranks in a field that is still figuring out how it wants to capitalize on the troves of data it collects.

"My vision for the role is data should be touching every portion of the company," he said.

Wells Fargo's head of innovation is in charge of pushing the company to develop new technology. The company tapped Steve Ellis — a 28-year veteran of the company — for the role. Ellis (left, in the photo above) took over last summer, and has overseen the launch of Wells Fargo's fintech incubator for startup companies.

His innovation group includes about 100 employees, working on projects such as biometrics, data security and authentication, he said.

Ellis, notably, doesn't have "chief" in his title — he's an executive vice president — but says he prefers it that way. "I wouldn't want the chief thing," he said. "What matters to me is getting stuff done."

In a straitlaced industry, Ellis has spent decades following his own path. He is a self-described "Deadhead" (a nickname for fans of the Grateful Dead, the rock band led by the late Jerry Garcia). Before he got into banking, he managed a bar and sold microbrews in Oregon.

After joining Wells Fargo, he quickly worked his way up to senior-level roles in treasury management and wholesale services. Along the way, he "caught the Internet religion" and was instrumental in pushing the company to develop mobile technology.

He also has encouraged his colleagues to loosen up a bit.

"I was actually the guy who helped drive casual Fridays to be casual every days," Ellis said, discussing his department's dress code.

Ellis, 61, said he did not start out with the intention of climbing the corporate ladder. But he is proud of what he has accomplished at Wells Fargo.

Rather than planning his next move, he said he has begun to think of retirement. "I see a future of snowboarding."

From the Department of Happiness: Chief Culture Officer

Having more fun has become a serious business in banking.

Over the past few years, banks across the industry have tried to shake their reputations for being hard-charging and stuffy. They have encouraged young bankers to take the weekends off and relax a bit more. They have also hired executives to manage workplace morale.

Enter the chief culture officer.

One of the many reasons for the rise of culture gurus in the industry — and perhaps most prevalent among them — is the more casual attitude that millennials have toward the workplace than their older peers. (

"The new attitude is, 'I want to have fun. I don't want to sacrifice today for tomorrow,' " Taylor said.

Investors Bancorp in Short Hills, N.J.,

Before joining the $21 billion-asset bank, Budinich worked as a consultant in the field of "positive psychology," which he describes as the study of optimistic thinking.

When Budinich, 60, talks about his job, he exudes a level enthusiasm that is rare in a buttoned-up industry.

"In order to be a great company — to be the best in class — feeling and emotion and outlook in life matter," he said.

Budinich runs employee training and development programs at Investors. He also organizes social outings, and sends a lighthearted email called "The Morning Juice" to employees every day.

The goal is to cultivate a positive workplace, in part because optimistic people simply sell more. "My job is to keep people in love with the bank," Budinich said. "It distracts them from the heavy load that they carry."

Budinich said he is especially pleased with a project he worked on last year, helping to keep employees' spirits high during a stressful core conversion.

The switch was hard on the bank's older employees, who had used the same system for decades, he said.

In addition to training employees on how to use the new system, Budinich took extra steps to help the company's "mature, legacy employees" cope with the change. "We had to keep people in the game, to not get upset and stress out," he said. "Culture had to get involved."

Before he was a banker, Budinich ran a wholesale bakery, selling zucchini bread — his family's special recipe — to high-end grocery stores in New York. He also opened a restaurant in Vermont.

The experience taught him that "you can sell ideas," he said, recalling what it was like to persuade stores to buy his family's bread.

But two decades ago, Budinich left his business ventures behind for a career in banking, working in various roles at banks such as First Fidelity in Newark, N.J. (It was acquired in 1994 by Wachovia, which, in turn, was absorbed by Wells Fargo during the financial crisis.)

Budinich said he got into his current line of work during a "low period" of his life, after he started working in banking. Around that time, he read "Think and Grow Rich," a 1930s self-help book by Napoleon Hill, a founder of the modern self-help movement.

The book changed his life. "I read it about 10 times," he said.

Though he loves his work at Investors, he would like to go back into consulting someday, to help employees at other banks across the country.

"We live in a world that doesn't provide many opportunities to find happiness," he said.

In the meantime, Budinich — like banking's other new C-suite executives — is pushing bankers to keep an open mind, and embrace the rapid pace of change in a once slow-moving industry.

— Bonnie McGeer contributed to this article.