Wells Fargo may soon have to begin selling parts of its massive branch network if it cuts back on cross-selling as a result of its phony account scandal, analysts said Thursday.

The San Francisco bank has struggled in the aftermath of revelations that it opened roughly 2 million fake accounts. Many blame cross-selling, which has been essential to Wells' business model, for the fraud. As a result, the bank is expected to cut back on its aggressive sales tactics, which may spur it to close branches as well.

"It is incumbent on the company to overreact and minimize cross-selling in the near term to ensure the company does not have to ensure political grandstanding," Mike Mayo, a bank analyst at CLSA, wrote in a research note on Thursday. "In short, Wells' mishap requires a strategic pivot, and it could consider branch reductions as part of that strategy."

The bank is also trying to put a new emphasis on digital distribution. Tim Sloan, who became chief executive on Wednesday after John Stumpf resigned, emphasized the creation of a new unit this week dedicated to virtual payments and digital innovation.

Mayo said that Wells' new focus on digital channels could "accelerate Wells' transition from traditional retail branches to virtual banking channels and eventually lead to 1,000-plus branch closures."

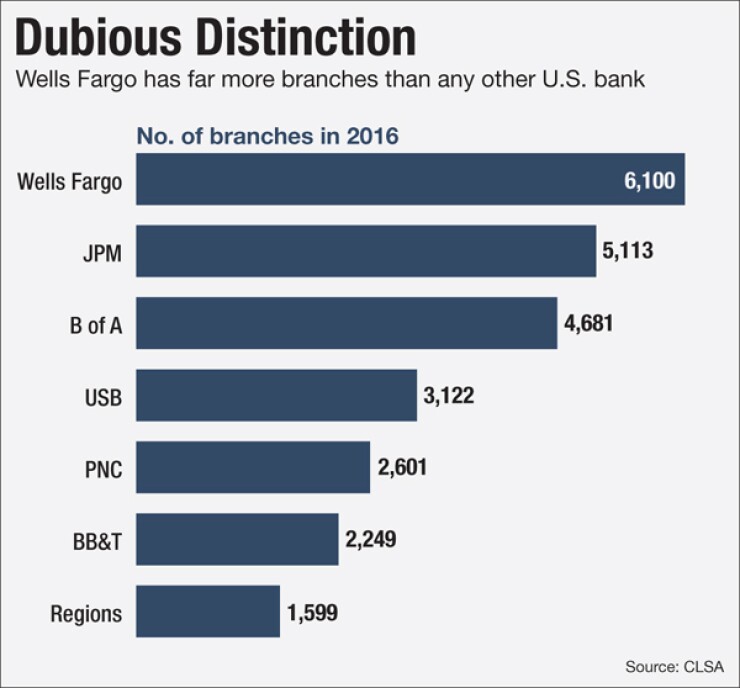

Wells currently has 6,100 branches — 10% more than its nearest competitor JPMorgan Chase and 30% more than Bank of America.

Those branches exist in part so that Wells can easier try to cross-sell products to its customers. Stumpf was widely mocked in recent congressional hearings because he'd encouraged branch employees to attempt to sell eight products to each customer because "eight rhymes with great."

Yet it's not clear how quickly or how far Wells will walk away from cross-selling. Asked about the strategy in an interview on Wednesday, Sloan signaled that it remains a key part of the business model.

"I have a really good appreciation of what drives the wholesale banking business and that is we've got a relationship-focused business model of bringing more products and services to our wholesale customers, making sure we deliver those in an appropriate way and take the right risks," he said.

Still, the writing may be on the wall. Brian Kleinhanzl, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, said he does not expect big changes across Wells' branch structure just yet, but acknowledged that the long-term secular trends "are moving digital."

"We expect branch closures to continue as long as they can do it without disrupting the customer base," Kleinhanzl said. "If you have issues with your customer base, it can make it more challenging."

Wells has only consolidated a small number of branches since 2010, Mayo said, while JPMorgan Chase has cut branches by roughly 9%, or about 150 branches a year. B of A has eliminated 17% of its branches in the past few years and expects more reductions ahead.

Wells could also boost earnings by reducing branches. If it cut 1,300 branches, or 23%, it would save $5 billion in pretax earnings, which would include all related expenses, Mayo estimated.

Some analysts said Wells can move beyond the scandal because the financial impact of the illegal sales practices so far has been negligible. The company paid $185 million in fines, but just $2.6 million of the $5 million set aside for to reimburse affected customers as part of the settlement.

"Helped by Wells' well-diversified business mix and solid earnings power, the financial impact of the sales practice issue should be manageable," John Pancari, a senior managing director and senior equity analyst at Evercore ISI, wrote in a research note Thursday.

Still, it is unclear what the full financial impact may eventually be from fines, remediation costs, forgone deposit and card revenue, lost revenue from municipal bond underwriting and higher compliance costs. There also may be other settlements with the Department of Justice, the Labor Department and state attorneys general.

Investors are hoping some of the pressure may be off after Stumpf's departure.

Eric Oja, an analyst at CFRA Research, called the sudden exit of Stumpf a "significant positive" for the bank because it "will quiet down the congressional and regulatory backlash seen" in the last few weeks.

Oja issued a buy recommendation on Wells with a 12-month price target of $50 a share. He also thinks Wells is well positioned for a possible interest rate increase in December.

An environment of higher interest rates is one reason some banks are reluctant to close branches, which can earn a higher return on assets when rates rise.

"When rates move up, the profitability of the branches moves up dramatically," Kleinhanzl said. "But we've been talking for five years about rates moving up."

Mayo said he wants Wells to grab "victory out of defeat" by making 1 million phone calls to customers who were impacted by the unauthorized accounts and to give $100 million to the roughly 115,000 customers who were charged fees.

"Management changes are better late than never for a crisis management scenario that has been about the worst that we've seen," Mayo said.