-

Still reeling from underwriting guidelines that went into effect last year, some small lenders are worried that a new mortgage disclosure regime might be the thing that pushes them over the edge.

April 14 -

Independent lenders rebut suggestions that they pose a greater risk to FHA (and hence taxpayers) than the large banks.

April 8 -

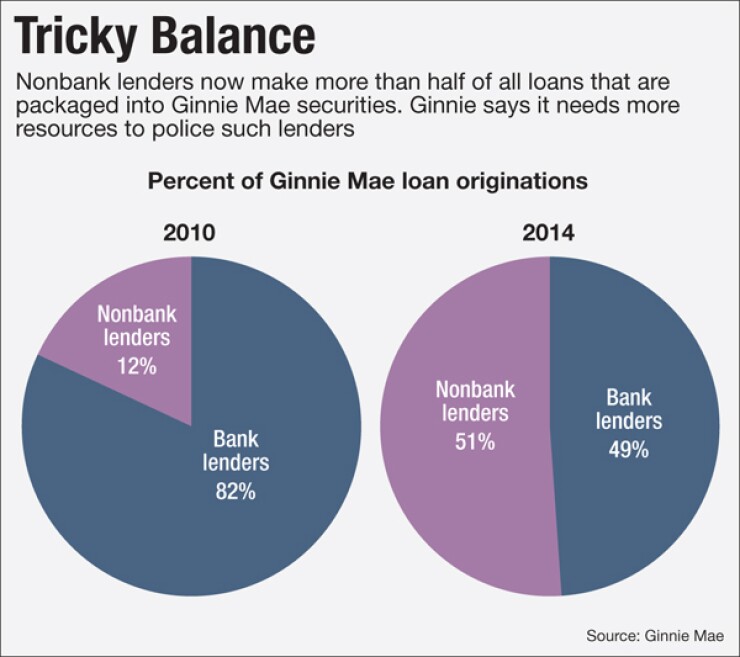

The shift in market composition is fueling concerns that if defaults rise, the Federal Housing Administration would have a harder time making lenders eat the losses on poorly underwritten loans.

April 6 -

Some nonbank issuers of mortgage-backed securities are wrestling with capital pressures, and Ginnie Mae has cooperated with their efforts to sell chunks of mortgage-servicing-revenue streams to investors.

March 31

As banks have largely ceded the

Most such lenders and servicers are in fine shape now, but any number of events

It's a huge concern for Ginnie President Ted Tozer, who says the company does not have the resources or manpower to examine these firms' finances. He's asking Congress to increase Ginnie's budget to ensure better oversight of nonbank lenders and servicers.

"We're in uncharted territory," Tozer said in a recent interview. "These nondepositories are really good companies, they're really well-run, but the Achilles heel is liquidity. Their financing structures are really complicated and we need the staff to analyze them."

Though no Ginnie issuers have defaulted of late, Tozer said Ginnie's staff spends lots of time counseling nonbanks on what to do "when they're feeling the pinch."

So far, a handful of small nondepositories have struggled to raise cash to fund their operations. Some have been advised to sell off mortgage servicing rights ensuring they don't get in a bind that could lead to a default or an inability to pay bondholders, Tozer said.

The issue is critical because Ginnie must ensure that issuers have the financial wherewithal to make principal and interest payments to bondholders. Ginnie securities are backed by loans that are guaranteed by the Federal Housing Administration, the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Rural Housing Service.

Since mid-2011, six large non-depositories Freedom Mortgage, Lakeview Loan Servicing, Nationstar Mortgage, Ocwen Loan Servicing, PennyMac Loan Services, and Quicken Loans have catapulted into the top 10 ranks of Ginnie issuers. They have replaced large and regional banks, including Citigroup, Flagstar Bank, PNC Bank and SunTrust Mortgage, that have shed market share in the past few years.

Nonbanks' share of just FHA-backed home loans has jumped to 62%, while large banks' share has slipped to just 30%, according to Ginnie data.

The dramatic shift has created an oversight challenge for Ginnie, which long relied on the Federal Reserve and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency to determine the safety and soundness of its issuers.

Tozer said he now finds himself in the position of doing due diligence on nondepositories with very little backup.

Moreover, some of the largest nonbanks including

Though the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the 50 states

"There's really no regulator when it comes to the financial stability of nonbanks," Tozer said.

Christopher Whalen, a senior managing director at Kroll Bond Rating Agency, agreed.

"There is no prudential regulator for nonbanks at the federal level," Whalen said. "There is a liquidity concern and a capital concern."

Vincent Fiorillo, head of global relationship management at investment firm DoubleLine Capital, said ensuring that payments continue to be made to investors, especially when a loan defaults, is critical.

"Of course it's a concern for Investors," Fiorillo said. "Investors want transparency."

Mortgage servicing is a cash-intensive business. Servicers can easily run aground, and eat up wads of cash, because when a loan defaults they are still required to continue advancing principal and interest payments to bondholders.

For some defaulted loans, that can mean making these advances for three years or more before they ultimately get reimbursed when a loan goes through foreclosure and final disposition.

"For nonbanks, the question is 'where is that cash flow going to come from?'" said Mark Garland, the president of MountainView Servicing Group in Denver. "If it's not from existing cash flow, it's from lines of credit. A servicer might have all the liquidity in the world but still be cash-starved."

In the past, Ginnie has used only a very basic and broad set of financial eligibility standards to address the financial capacity of its issuers. Tozer said he needs more analysts to understand the terms of, say, a nonbanks' preferred stock issuance or any constraints they may have rolling over debt.

Tozer is particularly concerned about how servicers will manage during a period of rising rates.

"We want to make sure a non-depository can get through a potential liquidity crisis," Tozer said. "As the (Federal Reserve) starts tightening, we want to have a mechanism in place so we are ahead of the game, if there are potential crises coming up or if there's a squeeze."

Ginnie has a staff of 145 and a budget this year of $23 million. For 2016, Tozer is asking Congress for a 20% budget increase to $28 million, which would allow the agency to hire about 30 people. For 2017, he wants a $10 million to $15 million budget increase.

"What I'm asking for is a drop in the bucket compared to the amount of risk we're trying to mitigate," Tozer said.