-

Consumer advocacy groups are urging regulators to take a closer look at how alternative lenders are using the stockpiles of personal information they collect.

October 2 -

In comments to the Treasury Department, traditional financial institutions are calling for more oversight of an industry that is fast becoming a big competitive threat.

September 30 -

A small Internet-focused bank plans to offer Prosper Marketplace's personal loans directly to its own customers through the bank's website. Prosper could use it as a template for deals with other banks.

September 15 -

Online marketplace lending platforms are filling real needs. But few banks participate in this booming niche, reflecting the industry's risk aversion and regulatory concerns as well as resistance to change.

January 22

It's like asking a toddler to dive into the pool for the first time: the child wants to jump, but the fear of the unknown keeps him from taking the plunge.

A similar situation is taking place with banks and online lending.

Kabbage, based in Atlanta, is one of many nonbank alternative lenders looking to partner with deposit-funded banks. The firm is aggressively trying to sell licensing rights for its technology, which can help banks expand their sources of revenue generation by adding short-term consumer loans and more small-business loans, and reduce their reliance on traditional strongholds like commercial real estate lending.

Lending Club is also keen on working with more banks, Richard Neiman, the San Francisco company's head of regulatory and government affairs, said during a recent panel discussion at a community banking conference hosted by the Federal Reserve Board and the Conference of State Bank Supervisors.

But leaders of small and midsize banks, by and large, have been lukewarm, or outright reluctant, to accept those overtures, worried that online lending could also lead them down a dark path filled with scary monsters, like the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and hackers.

"There are banks that wouldn't touch this with a 10-foot pole," said Chris Marinac, an analyst at FIG Partners. "Banks get tripped up by this kind of thing because there's this fear of the unknown, and that the CFPB will huff and puff and blow their house down."

It's not just Kabbage's online focus that scares bankers. The company uses something that many bankers consider far more sinister: underwriting criteria other than FICO credit scores.

"I saw Countrywide do that, so I'm not going there," said John Pollok, chief financial officer and chief operating officer at South State Bank in Columbia, S.C. "I know how to lend money. I'm not going to rely on someone else's black box."

About 53% of the $8.1 billion-asset company's loan book consists of consumer loans, including residential mortgages. South State may expand into online consumer lending, but it would only use technology developed in-house, and it wouldn't outsource the underwriting, Pollok said.

Some policymakers believe that banks and nonbanks should work together.

Collaboration between the two sides could lead to increased lending to small businesses, Fed Gov. Lael Brainard said during last week's community banking conference. "By working together, lenders, borrowers, and regulators can help support an outcome whereby credit channels are strengthened, and the possible risks are being proactively managed," she added.

Brainard spoke to bankers' concerns about fair-lending compliance, noting that banks must carefully vet the underwriting practices of online lenders. "To the extent that the underlying algorithms used for credit decision-making use nontraditional data sources, it will be important to ensure that this does not lead to disparate treatment or have a disparate impact on a prohibited basis," she said.

Some banks have already moved into online lending, either by launching their own platforms or partnering with nonbanks.

The $184 billion-asset SunTrust Banks in Atlanta bought online lender FirstAgain in 2012, and later relaunched the division as LightStream. The business makes

The $714 million-asset Marlin Business Bank in Salt Lake City, which doesn't have branches, in July unveiled an online portal for small-business loans of $5,000 to $100,000.

And on Monday, Regions Financial announced an agreement to partner with Fundation Group, an online small-business lender, to sell co-branded loans through Regions.com.

Of course, the risks for banks vary depending on the specific nature of the partnership. Many banks refer customer leads to online lenders such as Lending Club and Prosper Marketplace, a relatively simple arrangement compared with agreements to outsource underwriting to a nonbank.

Cross River Bank in Teaneck, N.J., goes as far as issuing loans on behalf of alternative lenders, a setup that allows the nonbank firms to avoid state-by-state interest rate caps.

More banks should be looking at products that embrace marketplace lending, Gilles Gade, the $382 million-asset bank's chairman, president and chief executive, said during a panel discussion at the Fed's community banking conference.

"Let's embrace technology rather than treating it like a threat," Gade said, adding that bankers simply need to "own the relationship" with alternative lenders by implementing strict monitoring and oversight.

More banks should consider online lending because they need to find new ways to generate higher-yielding assets and expand profit margins, Marinac said.

"The old business model of having a ton of commercial real estate isn't going to work anymore," Marinac said. "Banks should not wait forever to consider alternative lending."

Marinac said banks with no current exposure to consumer loans could diversify their portfolios by devoting about 1% to consumer lending.

"We're not advocating going to 20% or 30% into this," Marinac said. "This can be a viable business for banks, especially if you're just putting your toe in it and not your entire leg."

At a conference last week hosted by FIG Partners, Kevin Phillips, Kabbage's head of finance and accounting, made his sales pitch to banks during a panel discussion. Banks, he said, have a very different set of strengths than Kabbage.

Banks have a cost of funds that Kabbage "can only fantasize about," Phillips said. Kabbage funds its loans by obtaining credit facilities or other financial arrangements from outside sources.

Banks also have ready access to customers' checking and savings accounts, whereas Kabbage has to request permission for that access, he said. Getting electronic access to a customer's bank account makes it more likely that the lender will be repaid.

For its part, Kabbage offers a sophisticated online platform for accepting loan applications. These are essential in the world of online consumer and small-business loans, CEO Rob Frohwein said in an interview.

"Banks realize the time has come to address this market and that it's not going away," Frohwein said.

But then there's the part about how Kabbage makes credit decisions.

Kabbage touts its massive pile of consumer data. It has 50 terabytes of data on consumers, pulled from sources ranging from social media to UPS shipping volume. A team of Ph.D.s in California and India crunches numbers to form the basis of credit decisions.

That's the part that causes grave concern for many bankers.

"I need to be able to look somebody in the eye to decide whether he can pay back that loan," said Sammie Dixon, chief executive of the $229 million-asset Prime Meridian Bank in Tallahassee, Fla.

There's good reason for banks to be wary, said Sal Inserra, an accountant at Crowe Horwath who advises financial institutions.

"There's a risk associated with the reliance on someone else who's controlling the data," Inserra said. "What if they make an error when they update the data? What if they change something?"

If a bank makes online consumer lending a significant part of its balance sheet, its management "better understand how it works and know how the secret sauce is made," Inserra said.

"What if you find out that it's a magic eight-ball" being used to make credit decisions, Inserra asked.

The Kabbage product can be configured to handle an individual bank's specific risk appetite, Frohwein said. If a bank only wants to use an applicant's FICO score as the basis for underwriting, Kabbage can do that, he said.

As for regulatory concerns, Kabbage has discussed its model with regulators for years, and "it's something we're comfortable with," Frohwein said. Bankers, too, need to take the time to understand what they're buying into.

"There are plenty of ways to say no, but if they want to be able to serve these types of markets, it's imperative that they do the hard work to figure out a way to do it," Frohwein said.

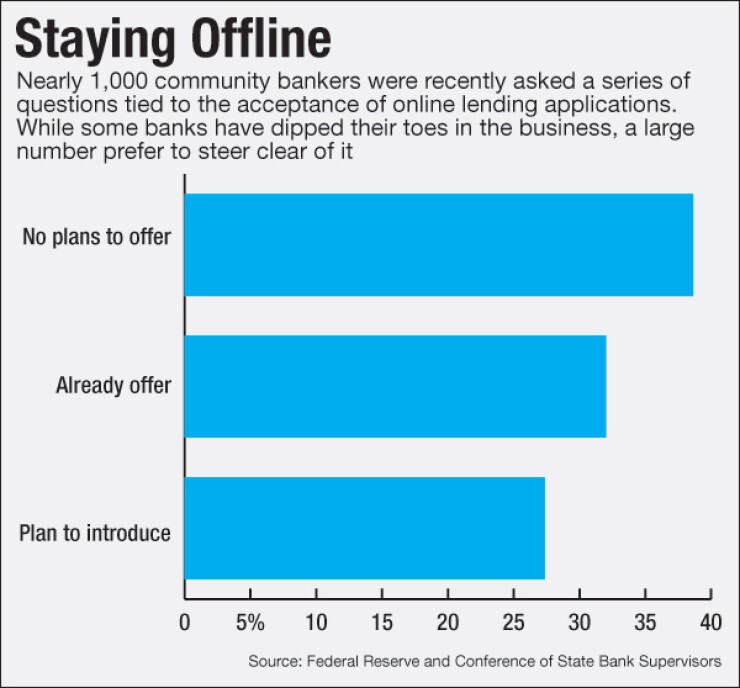

Community bankers, however, are split on online lending, according to a recently released survey by the Fed and the Conference of State Bank Supervisors.

Nearly 30% of the 974 respondents said they plan to introduce the services, but 39% made it clear that they have no interest in doing so. Compliance and cybersecurity are the chief reasons community bankers have balked at expanding into that line of business.

"We're not getting into anything exotic right now. We're focusing on core banking," Dixon said. "With all the fair-lending stuff going on right now and the CFPB, there's just too much unknown for a bank our size to do online lending."

Kristin Broughton contributed to this report.