When it comes to capital raising, there are several good reasons to consider issuing subordinated debt. For starters, it doesn't dilute existing shareholders like a stock offering would. The interest payments, unlike dividends, are tax deductible; and the proceeds, considered Tier 2 supplementary capital at the holding company level, count as Tier 1 capital if transferred to the bank.

But the main reason why subordinated debt issuance by banks is on the rise now following a long drought is renewed interest from investors.

After years of worrying about banks' survivability, and seeing few other opportunities for yield in fixed-income, investors are again willing to tolerate the risk of subordinated debt, which generally ranks below senior debt but ahead of equity in the event of a bankruptcy.

"Sub debt hadn't really been an option over the last six or seven years, but it has started coming back as a vehicle for community banks in the last six months or so," said Lee Bradley, managing director of Community Capital Advisors. "The feeling among investors is that it's safe to get back into community banks again."

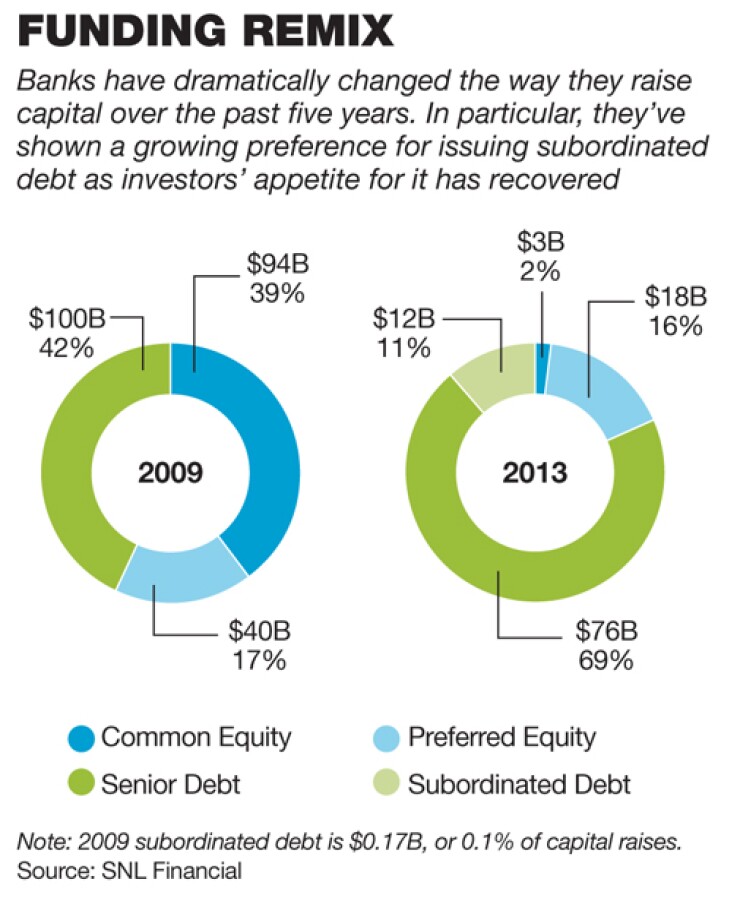

Smaller banks now have more options for capital than at any time since 2008, and they have responded by ramping up issuance of many fixed-rate instruments. Senior debt remained the most common form of bank debt last year, as it has been since the financial crisis. But subordinated debt issuance is growing faster.

Last year, public U.S. banks and thrifts sold about $12.3 billion in subordinated debt, according to SNL Financial. That's more than four times what they issued from 2009 to 2012, and it dwarfs the $2.7 billion in common equity that public banks issued last year. (The data does not include unregistered offerings and subordinated debt issued by privately held banks.)

Institutional investors in particular have sought out community bank debt in the past year, helping revive the market. There also has been a growing willingness of retail investors to buy and of retail brokers to sell community bank debt. Several small institutions have responded by conducting subordinated debt placements in recent months, including Georgia's Piedmont Bancorp and North Carolina's NewBridge Bancorp. Among regionals, Zions Bancorp. has conducted several large offerings in the past year through its online broker-dealer. And there may be more activity to come; Fidelity Southern in Atlanta and Seacoast Banking Corp. of Florida are among the institutions that have recently filed shelf registrations that would allow them to issue the debt.

On the buy side, several new vehicles have cropped up specifically to invest in these types of issues, including StoneCastle Financial, which raised about $110 million in a public offering last year and has focused on investing in community bank debt and preferred stock. EJF Capital in Arlington, Va., launched a subordinated debt fund last year that generally invests $4 million to $15 million in five-, seven- or 10-year community bank subordinated debt. The investments usually are in "private institutions that don't have great access to capital" and want to either refinance existing debt or grow, says Heather Rosenkoetter, an EJF managing director.

Peter Weinstock, a partner at the law firm Hunton & Williams, says interest rates on subordinated debt are generally running from 4% to 6% for retail issuances and from 7.5% to 9% for institutional offerings. The choice between a retail and institutional offering is a trade-off; while the cost of capital is lower at the retail level, it can be harder to line up buyers.

"I always tell a bank that, if they can get a local deal, they should do that," says Josh Siegel, CEO of StoneCastle Partners, the parent company for StoneCastle Financial's external advisor. "A community banker recently told me he could do a retail offering at 6%, and I said, 'You should grab that. JPMorgan can barely get that rate.'"

But not everyone is rushing to market. "Most banks have excess common and preferred stock and don't need to add sub debt to their structure right now," says Jefferson Harralson, an analyst with Keefe Bruyette & Woods. "But at least the option is back."