Just days before Easter, a community bank foreclosed on Faith Christian Church in Lakewood Ranch, Fla. Like other church foreclosures across the country, the story made headlines—a public relations nightmare for banks.

In this case, Pastor Tim Smith was forgiving, telling a local newspaper, The Bradenton Herald, he had no ill will toward the bank. "They had every right," Smith said. "We couldn't pay our mortgage."

But he also said that he had expected Easter service to be the last one at the church, and that the bank could have been more understanding about the timing.

Church foreclosures, a particularly prickly problem for lenders, have hit a record high, with the recession decimating contributions from congregations of all types nationwide. Lower property values and overly optimistic expansion projects are also to blame.

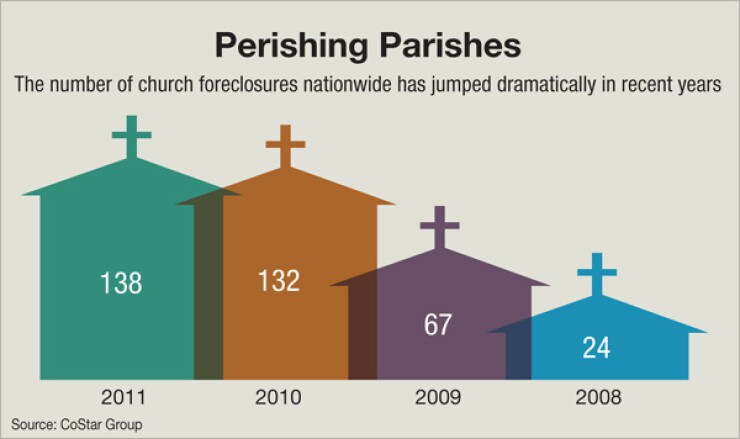

In the past two years, 270 church properties were sold after a loan default, 90 percent of them by banks, according to data from CoStar Group. The jump in foreclosures is striking: there were only 24 sales in 2008, and a mere handful during the decade before that.

Even so, several banks that have specialized in church lending for decades say they have never foreclosed on a religious facility. These banks are now refinancing troubled church loans made by others during the more prosperous years before the financial crisis. They contend church lending can be a lucrative niche—for those who understand the unique underwriting criteria involved.

Bank of the West has 27 bankers dedicated to church customers, says Dan Mikes, executive vice president and manager of religious institution banking there. The bankers, who handle marketing, lending and servicing, are trained internally, as there are no formal training courses in the industry for church lending, he says.

Results suggest the approach at the $62.4 billion-asset San Francisco bank is working: not only has it never foreclosed on one of its church loans, it has needed to restructure only a half-dozen of them over the past two decades, Mikes says. Throughout the economic downturn, its 30-day delinquency ratio has never exceeded 25 basis points on a church loan portfolio of $1.3 billion.

In his view, one key to success is relying on a church's historic cash flow to assess its borrowing capacity. He says other lenders often project that the congregation and income will grow.

"Many competitors have assumed that capital pledge campaigns, which commonly precede physical plant expansions, could be perpetuated should the church not realize growth after building the new facility," Mikes says.

Church lending is so attractive to the $90 million-asset Citizens Bank & Trust Co. in Nashville, Tenn., that these loans make up 75 percent of its overall loan portfolio, says Deborah Cole, the president and CEO.

That's helped boost the spread on the loan portfolio to 5.29 percent as of the first quarter.

Citizens has only two dozen employees, and several are dedicated to servicing church customers, says Cole, who also regularly takes calls from pastors herself. The bank typically makes loans to churches within an eight-county area around Nashville, as well as in Memphis, where it has one branch.

The underwriting policy focuses on income statements, same as with traditional commercial loans, Cole says. Citizens analyzes a church's total debt to annual revenue, along with its membership giving, shock-testing each for varying scenarios.

Citizens also analyzes the expenditures of a church, which can vary by denomination, she says. For example, some denominations, such as Methodists, send payments to their national body, so the bank takes that into account. Some churches, especially those with a sizable music ministry, pay out more in salaries. Others operate food banks or provide shelter for the homeless.

"When we look at the expenses of a church, we have to determine which expenditures can be categorized as discretionary," Cole says. "So if the church got into a severe problem, what kinds of expenditures do they not need to make?"

The bank offers free courses in church financing, to teach the leaders about creating budgets, identifying membership funding sources and implementing appropriate financial procedures.

Citizens also tries to cross-sell bus and van loans to churches, as well as mortgages to members, and commercial loans to those who are business owners, Cole says. This effort is part of the bank's "aggressive" push to triple its assets by 2017, she says.

The $590 million-asset Cass Commercial Bank began making church loans 16 years ago in its hometown of St. Louis. Business was so good that, a few years later, it opened a loan production office in Santa Ana, Calif., to reach out to churches in western states.

Now 55 percent of its assets are church loans, says Chris Dimon, the bank's western division manager. There are five employees in the Santa Ana office where Dimon is based, including three loan officers. Virtually all of what they do is church lending. The St. Louis office also has four loan officers dedicated to handling churches across the Midwest and eastern part of the country.

Refinancing church loans made by other lenders has been keeping Cass busy lately, Dimon says. "Some of those loans are just too large, and now those churches are scrambling to find some way to keep those loans funded," he says. "Some conducted capital campaigns and the bank counted that as normal income. Then, when their capital campaign ended, they had much less income to support the debt."

Despite the willingness of lenders like Cass, Citizens and Bank of the West to work with the struggling borrowers that have been cast off by competitors, many churches are having trouble refinancing their debt. Appraisal values on their properties are generally the reason for the problem, Dimon says. Sales of distressed properties have caused values to drop, so the loan-to-value ratios are often too high to enable a refinancing.

Though church foreclosures are happening across the country, CoStar's data indicates the majority are in states where the housing market is struggling the most: California, Georgia, Florida and Michigan.

During the church construction boom, there were hundreds of banks and specialty lenders that financed expansion of facilities, but since the financial crisis sunk real estate values, a lot of lenders exited the business, Mikes says. Yet some are still in the business locally, like Citizens, and others, like Bank of the West and Cass, remain active in the sector on a nationwide basis.

All say the loans require special underwriting criteria—so much so that they can easily trip up banks without more experience. Considerations for Citizens include how long the church has been in operation and its composition. "If a newly formed church of two years requests a $4 million construction loan, that probably wouldn't fit into our lending pattern, because they're not mature enough," Cole says. "If their congregation is very small and interrelated-contributions mainly coming from one or two families—then what if those families moved?"

Bank of the West prefers to lend to churches that have boards of directors making the financial decisions, rather than just a pastor being in control. Boards comprised of individuals with diverse professional backgrounds, such as legal, accounting and engineering, are the ideal. "We look at the bylaws of organizations, which are typically in one of two categories: one where there is a board of directors and one where the pastor and perhaps other family members control the decision process. We tend to stay away from the latter or at least limit our exposure to smaller loans with the disclosure that if the relationship grows changes are expected," Mikes says.

Word-of-mouth is the primary method for attracting church loans, these banks say. Bank of the West gets referrals from existing church customers, networks with trade groups such as the National Association of Church Business Administrators, and sponsors that association's national conference every year, Mikes says.

Some advertising is used, though. Bank of the West regularly runs full-page ads in industry periodicals, such as Church Executive magazine.

For Mikes, the commitment to church lending is a point of pride. "These institutions do a lot of good for their communities," he says. "They provide food and clothing to the needy, they offer marriage and job counseling, and they provide family life centers, which have, in many instances, replaced the community centers municipalities can no longer afford."

Katie Kuehner-Hebert is a freelancer. She is based in Running Springs, Calif.