-

The influential blogger says it's time for a national debate on the role Experian and other credit agencies play in protecting and consumers' identity and privacy.

April 21 -

An organization calling itself Anonymous Ukraine has boasted of a huge theft of American debit and credit cards. Many of the card records are old, and some appear to be from earlier breaches. However, the claims have to be taken seriously, investigators say.

March 31

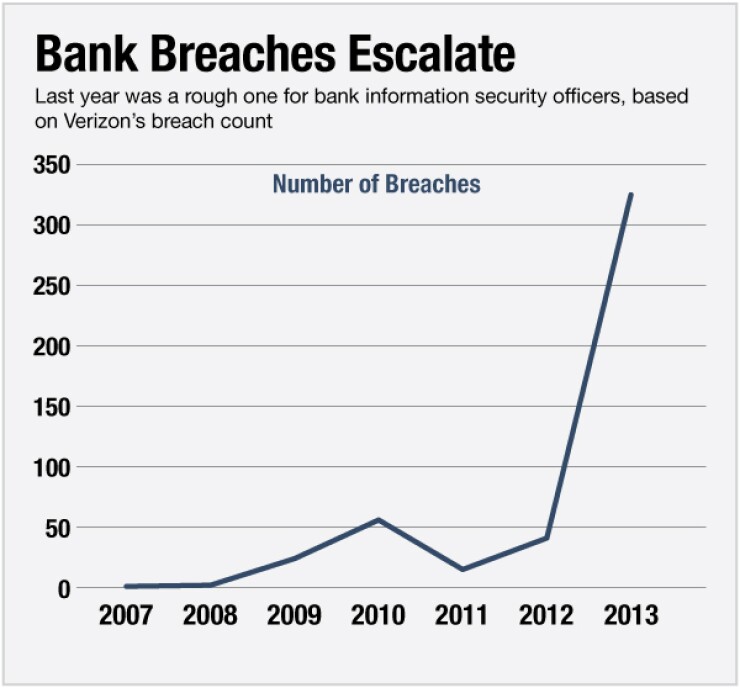

The Target card data breach dominated headlines last year, but it was just one of hundreds of hacking incidents to hit banks and expose the personal information of their customers, according to Verizon's latest Data Breach Investigations Report.

The biggest security threats to banks last year were web app tampering, distributed denial-of-service attacks, and the increased use of payment card skimmers, according to Verizon's widely trusted report, which was released Monday. These three categories of attacks made up three-quarters of security incidents targeting banks.

Verizon, with the help of 50 partners including law enforcement agencies, the Financial Services-Information Sharing and Analysis Center, government agencies, other forensic investigation companies, and research companies, tracked 1,367 confirmed data breaches and 63,437 security incidents in 95 countries.

More than one-quarter 27% of all security breaches at banks last year involved web app attacks, the report found. In web app attacks, cybercriminals use a variety of tactics to interfere with web applications. Many start with phishing, a fake email sent to a customer that appears to be from their bank that tricks them into sharing their user name and password, or into clicking on a link that leads to the installation of malware on their machine. Brute-force password guessing can also be used in a web app attack. A less-used type of web app attack uses SQL injection, in which a hacker inserts malicious SQL statements into an entry field for execution; for instance, to dump the database contents to the attacker. (Distributed denial-of-service attacks can also be web app attacks, but due to the volume and impact of DDoS, Verizon broke those out separately.)

"Web attacks are everybody's scourge," says Dr. Anton Chuvakin, research vice president, security and risk management at Gartner. "As the Internet is growing, all sorts of less-skilled programmers are deploying applications. You have fewer security-minded programmers."

In five years, we'll all still be talking about web app attacks, he says.

The goal of web app attacks on banks is often to steal online banking user names and passwords.

"A lot of organizations whose web apps are being successfully breached are those still using single-factor" authentication, says Chris Novak, global managing principal, risk team at Verizon Enterprise Solutions. "The perpetrators look at that as an easy avenue to get into any one of these environments."

This is one reason why several banks, including

The recently discovered Heartbleed bug has made many people rethink their website security, Novak says.

"The Heartbleed situation took the Internet by storm and all these organizations came out of the woodwork scanning their websites as if it was the first time they ever did it," he says. Security scans of websites ought to be routine for banks.

Another major threat is a distributed denial of service attack. Such attacks, while not technically data breaches, accounted for 26% of all bank incidents last year, according to the Verizon report.

They involve the launching of excessive, malicious streams of traffic at a web server in the hopes of slowing it down or stopping it altogether. The perpetrators usually don't try to steal data during an attack; they are generally trying to damage the integrity of a company's operations. Verizon included DDoS attacks in this year's report because they are becoming more widespread.

"It used to be that DDoS attacks were small and would pass quickly; a lot of organizations would put them by the wayside," Novak says.

Last year was the biggest ever for DDoS attacks; not only were there more incidents than in any previous year, the average size of individual DDoS attacks more than doubled from 4.7 gigabytes per second in 2011 to 10 gbps in 2013.

Many DDoS attacks last year went unreported in the press, but were investigated, Novak says.

"I think the reason they didn't make as big of a wave [as they did in 2012, the year the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Cyber Fighters began their high-impact series of attacks on banks] was because more organizations were successfully mitigating them," Novak says. Because of DDoS mitigation practices and technology companies have put in place, although they're getting hit, they're scrubbing a lot of the malicious traffic, allowing the websites to remain in operation.

The perpetrators of these attacks are hard to find because of the large number of decentralized proxy points used. Yet in some cases, as with attacks launched by Al Qassam and Anonymous, attribution is obvious.

A large majority are politically motivated, Novak says. Some are financially motivated the nuisance DDoS attack is just a diversionary tactic for a data theft taking place while security officers are focused elsewhere.

"We hear a lot of people theorizing about the smokescreen aspect, but that tends to be on the smaller end of the spectrum," Novak says.

Chuvakin wonders if DDoS will continue to be popular a year from now.

"DDoS for me is more of a fashion trend," he says. "As companies develop their defenses, the attackers may well lose interest in doing DDoS."

That payment card skimmers are a major point of entry for security breaches against banks is surprising. Someone sticking a plastic cover on a card slot at an ATM or gas-pump to grab card numbers can feel like small potatoes compared to a card database break-in. But for institutions with many ATM machines, they cause a significant hit, according to the report.

Last year, skimming incidents comprised 22% of attacks, according to Verizon.

"For a wide array of criminals ranging from highly organized crime rings to garden variety ne'er-do-wells who are turning out no good just like their mama warned them they would, skimming continues to flourish as a relatively easy way to 'get rich quick,'" the report authors explain.

ATM card skimming involves placing an illegal card reader over the machine's legitimate card reader, to capture the information from the magnetic stripe of each card as it's swiped. When the fraudsters feel they've gathered enough data, they remove the skimmer and use the information to create fake ATM cards.

One reason ATM skimming is widespread is because cybercriminals can create their own custom-made skimmers using 3D printers.

"You used to see a lot of these folks go to online auction sites to buy the equipment for a skimmer, or refurbish old equipment," Novak says. "Now we're finding these people are making them at home in their garage." A 3D printer costs around $1,000, he says, and allows for a perfectly customized fit with the targeted ATM.

Better yet, from the criminal's point of view, the work is untraceable.

Chuvakin also notes that some ATMs are in remote locations that are hard to monitor.

Perhaps the biggest challenge banks face in thwarting attacks is that criminals are improving and changing their techniques faster than banks can detect them.

"Their ability to up their game is increasing faster than our ability to block and tackle what they're doing," Novak says.

"Every year I joke with the Verizon team that [the detection metrics are] depressing," Chuvakin says. "Most people, even if they've been attacked badly, don't detect it." Often this is not because hackers are smart, but because the defenders are overwhelmed, under-resourced or simply not focused on the right things, he says.

In many cases, third parties such as business partners, security researchers or web site visitors spot an attack before the victim does. To Chuvakin, this is like a passerby seeing that a bank branch is being robbed, while the branch security guard notices two weeks later.

Novak believes attackers are getting more sophisticated. "More cybercriminals are collaborating and sharing infrastructure to make their attacks more successful," he says. "The decentralized way many of them operate gives them a better ability to remain undetected."