In late June, ICANN, the group that oversees internet domain names, lifted its restriction on internet address endings (also known as generic top-level domain names or gTLD) from the current 22, which includes such domains as .com, .org and .net, to infinity. Starting on January 12 (and ending April 12), anyone who wants to pay the $185,000 fee and fill out a 250-page application can apply for a domain name that suits their brand name (e.g. .bnymellon). This potentially opens up an opportunity to banks to market and brand themselves differently through their internet addresses and to offer more secure online banking - the new regime raises the scrutiny, money and effort required to register a new internet address.

But two issues that stand in the way. One that's been articulated by the American Bankers Association is the concern that whatever entity ends up controlling the .bank domain could either charge high fees to financial institutions wishing to protect their intellectual property or fail to securely operate such domains, damaging consumer confidence in the internet channel. ABA and the Financial Services Roundtable are exploring whether to apply to become a registrar for ".bank."

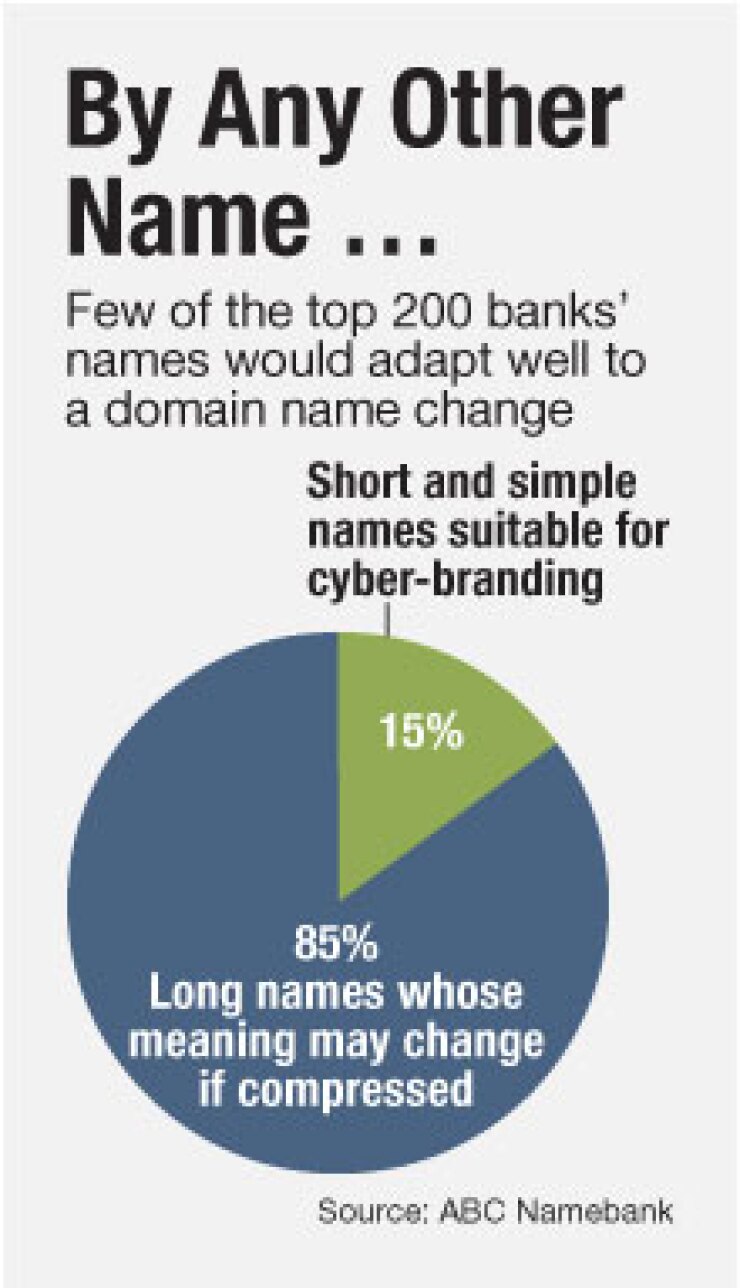

The other is that some banks will have a hard time taking advantage of their new domain-name liberty because of their klunky names, according to nomenclature specialist Naseem Javed, founder of New York-based ABC Namebank. "Of all the industries, our research shows that American bank names don't fit the proposed model of the gTLD because their name structures would disqualify them. If your name is Bank of Galveston or Bank of New York, it will not work with .bank. You cannot say .bankofgalveston. If you say BOG, it becomes .bog; that doesn't carry any place. The same goes for Bank of Commonwealth, Bank One, and Bank United." An egregious example he cites is The First Imperial Bank Depository of Commerce of the Commonwealth Dominion. More than 22 U.S. banks have names that begin with First, such as First American, First Capital, First Citizens, according to Javed. "American bank names are caught up in last century," he says. "We're living in the 21st century, with global interactions and online banking."

The most domain-name-friendly U.S. bank name, in Javed's view, was Citibank until it dropped the "bank." Using .citi would be confusing, he says. "Unless you say it in the context of a bank, people will not understand it," he says.

Once they do figure out the right specialized domain names, the new addresses should improve online banking security because of the tightened control over who can use which domains. . "The first generation of domain names cost $10 and there were no questions asked; you could go and get whatever you want," Javed says. "People in Turkey had IBMbakery.com and that was allowed." Today, between the steep fee and lengthy application process, "No squatter in their right mind would go spend six months and half a million dollars so they could mess around with Bank of America's name, then get sued the following week and get a cease and desist order. This is definitely a cyber squatting killer."

Banks can ignore the new domain names, but they may lose what Javed refers to as "cyber image warfare." "The question is, are they going to stand up to their name identity and dominate that name identity in cyberspace or will they just let it go, because banks have other issues on their plate right now," he says. "The fact remains that cyber branding in this complex global space is increasingly becoming important and all these foot-long names and names that have been clustered together are last century and they will run into difficulty."